Once upon a time—and it wasn’t that long ago—books were pretty distinctive.

There were picture books for young children, often read to them, often teaching some life lesson.

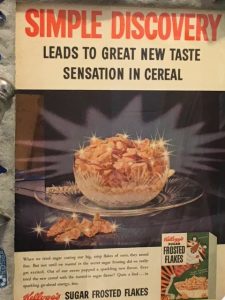

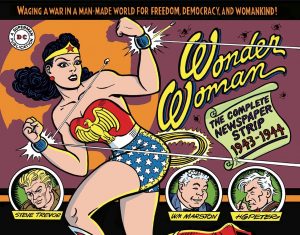

There were comic books, periodicals geared mostly for older children and teens, pretty much equal parts drawings and text. They were/are fast reads, typically 22 pages. Although all are called comics, many were action/adventure, super hero series. Advertisements abound.

Then there were “real” books, hundreds of pages of text, complicated plots, and virtually never with pictures. (Oh, yes, I must give a nod to so-called coffee table books, in which photographs are their reason to be. Such books tend to be incredibly expensive. I don’t think their existence undermines my general point here.)

Graphic novels are cartoon drawings that tell a story and are published as a book. Will Eisner is typically credited with popularizing the label “graphic novel” after the publication of his book in 1978. By the mid 1980’s, the public was generally aware of that genre.

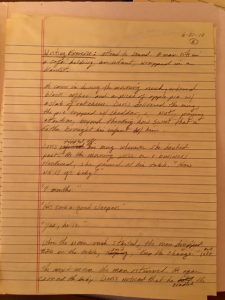

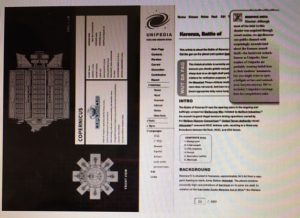

Last week, at the beach, I was introduced to yet another emerging book format. Illuminae is bestselling science fiction that tells the story through a mix of realistic graphics, ships logs, text messages, lists of the dead, etc. Unlike cartoon drawings, these are ultra-realistic, from the use of acronyms and abbreviations right down to the occasional typo in text messages. Here are what some of those pages look like.

This format continues in two subsequent books in the series. Perhaps people are embracing the visuals. Th the very least, readers are not deterred.

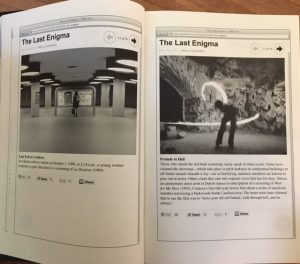

Another example of the changing looks of books is Night Film, touted as a gorgeously written, spellbinding literary thriller.

A friend read, recommended, and gifted the book to me. I haven’t read it yet, but just opening it at random I find large chunks of narrative and dialogue interspersed with realistic images representing everything from the results of on-line searches to purported magazine covers to newspaper articles.

And just to add another little twist, at the end of the book one finds the following page. It begins, “If you want to continue the Night Film experience, interactive touch points buried throughout the text will unlock extra content on you smartphone or tablet.”

All the traditional formats of books are still out there. Cathryn Hankla’s lost places was published earlier this year and is completely in traditional text format. It is being very well-received.

BOTTOM LINE: The visual appearance of books is evolving. I suspect it’s the massive moves in technology which allow such printing diversity. Readers have more choices than ever before. And so do writers!