I just found out that the US now has a derecho season every year. Reading about it lead me to all the fascinating and bizarre ways wind impacts the rest of the weather, many of which I discussed in this post from 2021.

According to the wind sock above, the wind when the photo was taken was blowing at about 6 knots (7mph). The sky is clear, the sun is bright, and there are no flying sharks. Unless you live in England or Seattle, this is nothing to write home about.

Even though you can’t actually see it, wind can create some pretty incredible things to write home about. Our ancestors definitely thought the wind was worth writing about, especially when it picked up everything around and sent it flying through the air.

Like snow, there are seemingly endless names for specific types of winds. If you really want to know about the difference between piteraq and bora winds, check out the World Meteorological Organization or National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration websites. I’ve included some of the most spectacular and most mythological wind events here.

Dust Devils

Suppose you experienced a Dust Devil? A small dust devil, say 18 inches wide and a few yards tall is a sight to behold. A BIG dust devil—say 33 feet wide and 1000 feet tall—can be terrifying!

An extreme dust devil can reach 60 mph and last up to 20 minutes. In the process, it could lift more than 12 tons of dirt, and the friction between wind and surface can create sparks often mistaken for lightning. In fact, dust devils are not associated with storms.

Dust devils have been known to lift roofs and collapse buildings, sometimes killing people. There are reports of them flinging animals and 10-year-old children about. Inflatable bounce houses are especially vulnerable.

Where do they come from? When hot air at ground level rises quickly and hits a pocket of cool/cold air, it can start to spin, forming a column of air. The spinning, along with friction from the surface, allows the column to move, picking up dust along the way. Dust devils are especially likely in deserts. Usually they cause little damage.

Other Names for Dust Devils

- Dancing devil

- Dirt devil

- Dust whirl

- Sand auger

- Sand pillar

- Redemoinho in Brazil

- Remoinho in Portugal

- Willy willy or whirly whirly in Australia

Beliefs About Dust Devils

- Chindi is the Navajo term for spirit or ghost

- Good spirits whirl clockwise; bad spirits spin counterclockwise

- Ngoma cia aka is the word for women’s spirit/ demon or women’s evil among the Kikuyu in Kenya

- Fasset el ‘afreet from Egypt, meaning ghost wind

- Many traditions on the Arabian peninsula include a djinn or afreet/ ifrit inside the column of dust

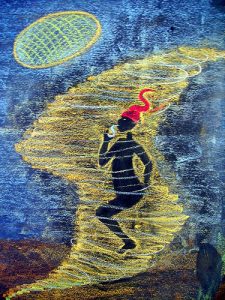

- According to Brazilian legend, Saci-Pererê lives inside the dust devil and grant wishes to anyone who can steal his magic cap

More Devilish Wind

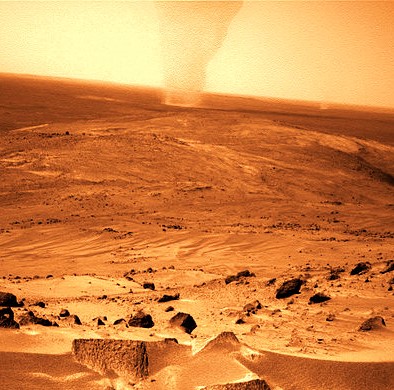

Martian dust devils form the same way as on Earth, but bigger: up to 10 times as high and 50 times as wide, with mini-lightning flashes. Dust devil trails on earth’s deserts usually disappear in a couple of days; on Mars, they remain visible (so I’m told) for weeks.

Snow devils develop when a strong wind hits a solid object (like a mountain), spins downward and lifts up snow, creating a vortex. They usually last only a few minutes, and they are small (seldom more than 30 feet across). Still not something one would want to be out in.

Fire whirls, aka fire devils or fire tornadoes, develop a vortex inside a wildfire. They are whirling columns of fire rising up into the air. They carry ash, debris, and smoke and feed the fire and spread it. There have also been reports of fire whirls at volcanos and during earthquakes.

Haboob (هَبوب) is a kind of huge dirt devil that can appear in deserts around the world, including the U.S., associated with thunderstorms. When the rain is released, it causes sand to blow up, making a wall of sand that precedes the storm. Haboobs can be several miles high and 60 miles wide.

Tornadoes

There are many varieties of tornado beyond those that transport Kansas farm houses to Munchkinland.

The actual definition of a tornado is a bit fuzzy, even among the experts. They can’t seem to agree on when one tornado stops and another starts. The swirling wind tunnel has to touch the ground and the clouds at the same time before it counts (that’s why gustnadoes aren’t really tornadoes, though I’ll include them here for ease of reference). Tornado experts judge tornado strength by size, wind speed, and distance over the rainbow it can throw a farmhouse.

Gustnadoes

Gustnadoes are closely related to dust devils, short-lived and ground based, but they have stronger winds (maybe as strong as weak tornadoes) and develop over open plains areas of the U.S. They don’t form funnels and may go unnoticed. Though a gustnado can cause serious damage, it’s not tall enough to register as a tornado.

Other Weird Winds

Firestorm

A firestorm develops when a fire becomes so big and intense that it creates its own storm-force wind systems. Firestorms are most often associated with wildfires and brush fires, but they can also be created when large sections of densely built cities catch fire.

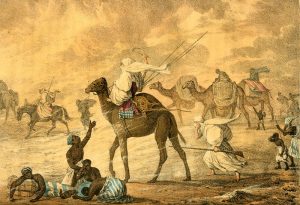

Sandstorm

Sandstorms (aka dust storms) don’t whirl or spin. It’s essentially a wall of wind that pushes sand in a more-or-less straight line. Wind strength can be strong enough to pick and move entire sand dunes great distances. Sandstorms occur worldwide, wherever deserts are found.

Khamsin

Each spring, areas along the eastern Mediterranean, North Africa, and the Arabian peninsula are hit by a khamsin (خمسين from Arabic word for 50). The khamsin is a 50-day wind that coats everything in sand and dirt.

In 2009, archaeologists may have found remains that appear to be those of a Persian army of more than 50,000 that vanished in 525 BCE. A strong wind that blew up from the south is suspected of covering them in suffocating mounds of sand.

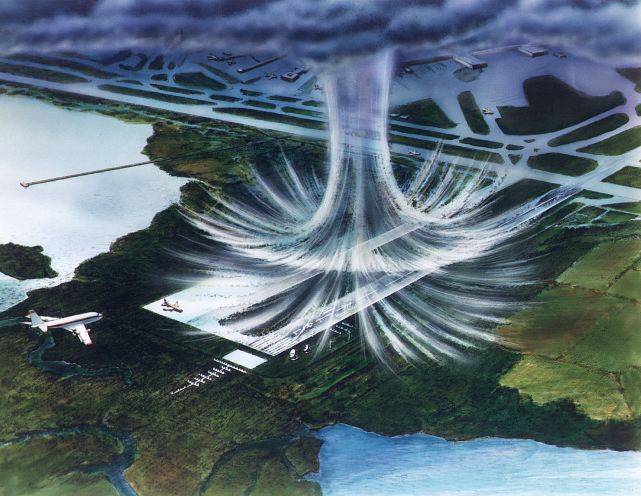

Downburst

A downburst occurs when the downdraft of a thunderstorm hits the ground and forces the air to gust outward and curl backward. As it moves horizontally, the wind can cause extensive damage to everything it passes over. The wind curling backward can cause further damage, creating tornadoes, waterspouts, snow devils, sharknadoes, and fire whirls.

- A macroburst happens when an extremely strong downdraft hits the ground. Horizontal gusts cover an area more than 4 km in diameter. These gusts can be as destructive as a tornado.

- Microbursts are smaller in size and shorter in duration. A microburst is less than 4 km across and short-lived, lasting only five to 10 minutes, with maximum windspeeds sometimes exceeding 100 mph.

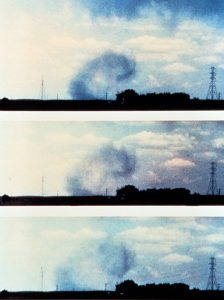

Derecho

A derecho is a widespread, long-lived wind storm that is associated with a band of rapidly moving showers or thunderstorms. A typical derecho consists of numerous microbursts, downbursts, and downburst clusters. By definition, if the wind damage swath extends more than 240 miles (about 400 kilometers) and includes wind gusts of at least 58 mph (93 km/h) or greater along most of its length, then the event may be classified as a derecho.

Ground Blizzard

Unlike regular blizzards, ground blizzards don’t involve any snow falling from the sky, but they are still deadly. Instead, snow that is already on the ground is whipped into whiteout conditions by an extreme cold front. Temperatures plummet, and snow on the ground is picked up by wind gusts up to 60mph. The Arctic cold fronts that cause ground blizzards also cause extreme low temperatures.

Every one of these wind events have been known to kill people! In addition, extremely hot or cold winds can do the same. Though we usually can’t see the air itself, the effects are pretty amazing!

Godly Winds

In Irish folklore, the Sidhe or Aos Si are the supernatural pantheon. Sidhe is used to mean fairies, but the Old Irish translation is “wind” or “gust.”

Deities connected to the wind are often closely related to those of the air. In many traditions, the same deity governs the air and the wind. Cultures heavily reliant on changes in the wind, such as seafaring communities or nomadic groups on open plains, tend to have more detailed and powerful wind and air gods.

One of the most famous wind gods in mythology is Aeolus, the Greek god governing all winds, who was closely involved in Odysseus’s voyage home. He is certainly not the only supernatural being in charge of the wind and air.

(by Andrey Shishkin)

Superhero Winds

If that’s not enough to convince you that wind and air hold a prominent position in our collective subconscious, just look at how many modern superheroes (and villains) have the names and powers of wind phenomena.

Bottom Line: We tend to think in terms of breezes or stiff winds, but there’s so much more to wind than that!