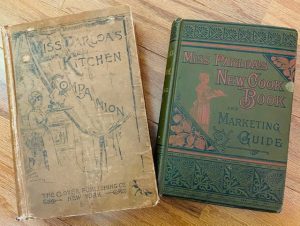

Because this is Women’s History Month, every day I’ve been spotlighting a woman on my Facebook page. But Fannie Merritt Farmer (1857-1915) deserves more than a paragraph!

(Note: Though she sometimes spelled her first name “Fanny,” Fannie Merritt Farmer was not affiliated with the Fanny Farmer candy company. Frank O’Connor named his candy company after the chef and food scientist in part to ride the wave of her fame in 1919.)

Early Culinary Training

Fannie Farmer was born on March 23, 1857, in Boston, Massachusetts. The oldest of four daughters in a family that highly valued education, she was expected to go to college, but suffered a paralytic stroke at the age of 16. Some say she contracted polio that permanently affected her left leg. In any case, for the next several years she was unable to walk and was cared for in her parents’ home.

Once she was able to walk again, she did so with a pronounced limp. At the end of her life, she was again confined to a wheelchair. And none of this kept her from achieving much and influencing virtually every household in the United States even today.

During the time she was homebound, Fannie took up cooking for guests in her mother’s boarding house. Not until the age of 30 did she enroll in the Boston Cooking School. The Women’s Education Association of Boston founded the Boston Cooking School in 1879 “to offer instruction in cooking to those who wished to earn their livelihood as cooks, or who would make practical use of such information in their families.”

Fannie enrolled during the height of the domestic science movement. The curriculum covered all the basics, including nutrition and diet for the well, convalescent cookery, techniques of cleaning and sanitation, chemical analysis of food, techniques of cooking and baking, and household management.

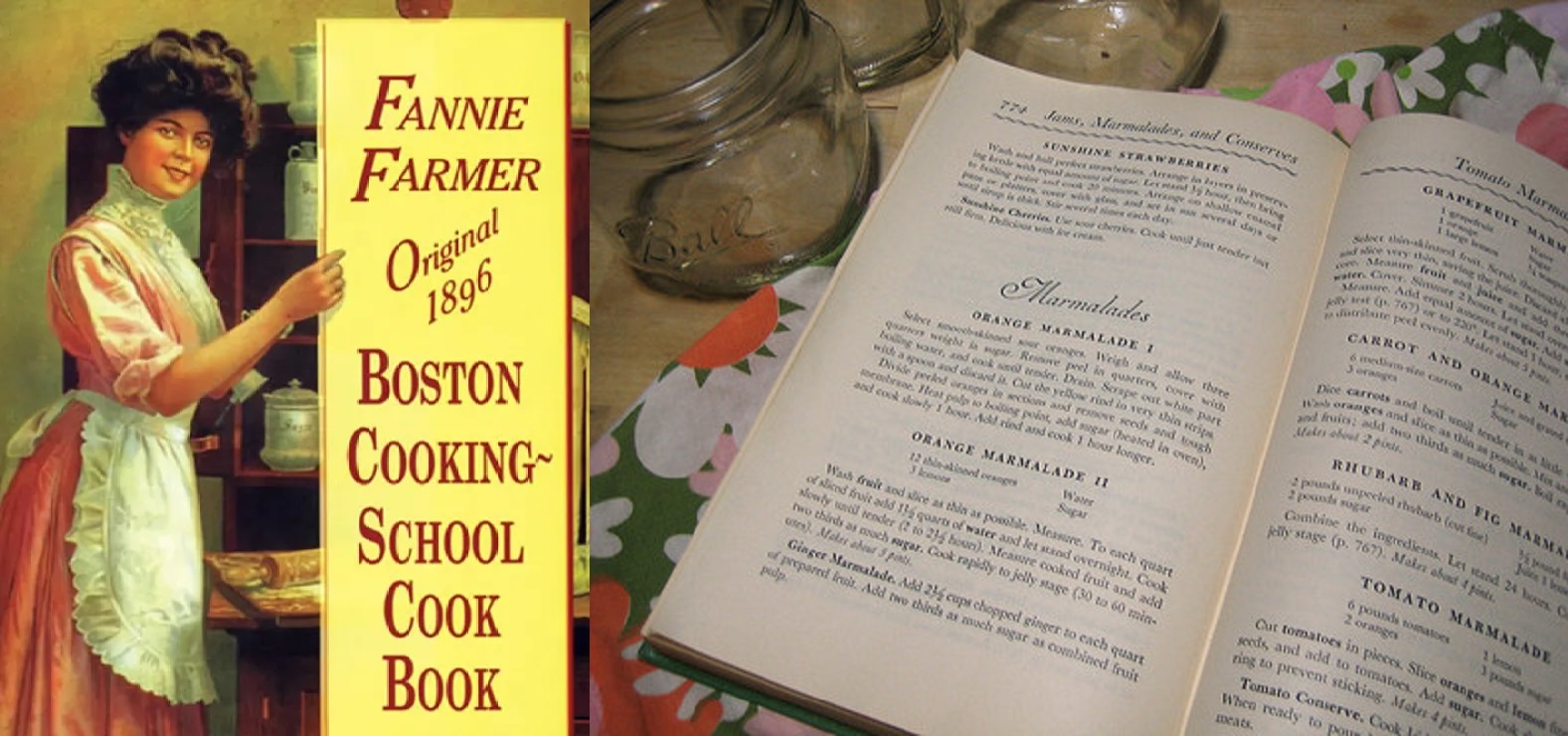

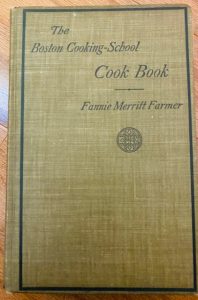

Fannie was one of the school’s top students. She graduated in 1889 and stayed on as assistant to the director, and in 1891, she became school principal. The school became famous after the publication of The Boston Cooking School Cookbook by Fannie Merritt Farmer in 1896.

Fannie Farmer Cookbook

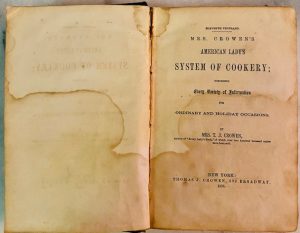

The publisher, (Little, Brown & Company) did not expect good sales and printed a first edition of only 3,000 copies—at Fannie Farmer’s expense! Thus she became an early “self-published” authors who made good. Subsequent editions were published as The Fannie Farmer Cookbook (or The Fanny Farmer Cookbook).

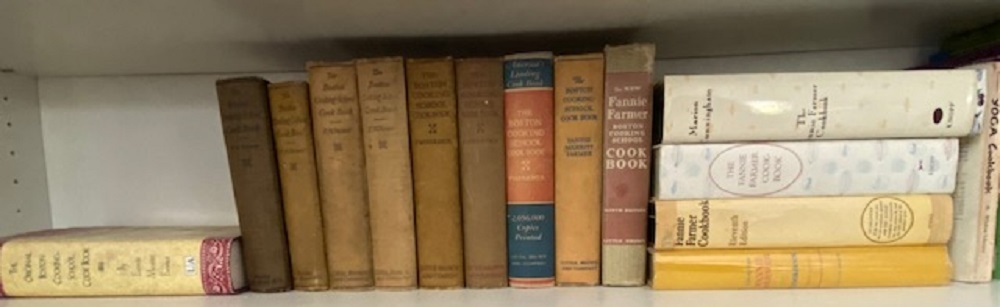

The cookbook was titled The Boston Cooking-School Cook Book through the eighth edition, published in 1946. The ninth edition, published in 1951, was titled The New Fannie Farmer Boston Cooking-School Cook Book. Not until the eleventh edition, 1965, did it become The Fannie Farmer Cookbook.

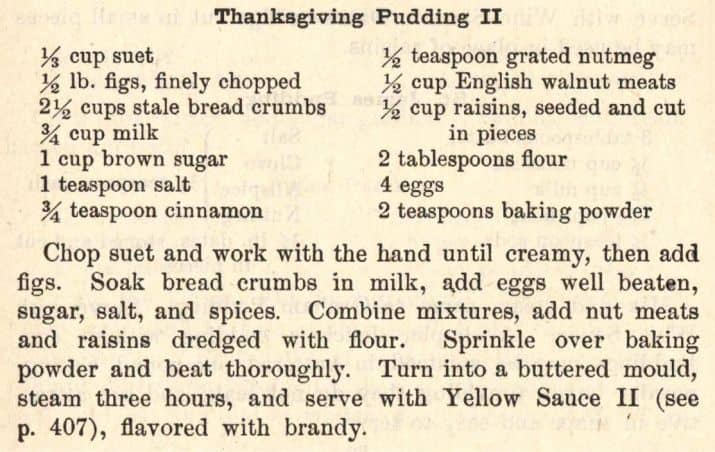

You can now read the entire 1918 edition of The Fannie Farmer Cookbook online!

Farmer’s book eventually contained 1,850 recipes. As was the custom for cookbooks of the day, she included essays on housekeeping, cleaning, canning and drying fruits and vegetables, and nutritional information. Farmer also provided scientific explanations of the chemical processes that occur in food during cooking,

And (in my opinion) the most important contribution for cooks today: she standardized measurements used in cooking throughout the US. I’m not alone in this; food historians have called her the “mother of level measurements.” Prior to Fannie Farmer, recipe authors listed ingredients as a lump of butter, a teacup of milk, a goodly amount of honey, … Level cups and teaspoons (or fractions thereof) as we know them today are thanks to Fannie Farmer.

Fannie Farmer’s Impact

Her cookbook was so popular in the United States—so thorough, and so comprehensive—that The Fannie Farmer Cookbook, went through twelve editions. By 1979, the Fannie Farmer Cookbook Corporation copyrighted and published The Fannie Farmer Cookbook, and Marion Cunningham updated the thirteenth edition.

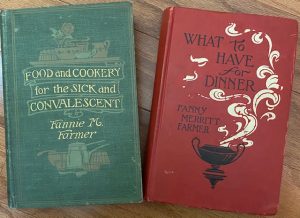

Farmer left the School in 1902 and created Miss Farmer’s School of Cookery. She began by teaching women plain and fancy cooking, but her interests eventually led her to develop a complete work of diet and nutrition for the ill, titled Food and Cookery for the Sick and Convalescent which contained thirty pages on diabetes.

Farmer gave lectures at Harvard Medical School, teaching convalescent diet and nutrition to doctors and nurses, and taught a course on dietary preparation at Harvard Medical School. She felt so strongly about the significance of proper food for the sick that she believed she would be remembered chiefly for her work in that field.

During the last seven years of her life, Farmer always used a wheelchair. Even so, she continued to write, invent recipes, and lecture, until ten days before her death. The Boston Evening Transcript published her lectures, which were picked up by newspapers nationwide. Farmer died in 1915 at age 57 of complications related to her stroke/polio.

She is interred in Mount Auburn Cemetery, Cambridge, Massachusetts. (Mount Auburn is my favorite cemetery and was the prototype for Hollywood Cemetery in Richmond, VA.)

Fannie Farmer’s Works

As far as I can tell, this is a complete list of her books:

- Farmer, Fannie Merritt (1896). Boston Cooking-School Cookbook. Boston, MA: Little, Brown, and Company. A complete list of editions may be found at Boston Cooking-School Cook Book.

- Farmer, Fannie Merritt (1898). Chafing Dish Possibilities. Boston, MA: Little, Brown, and Company.

- Farmer, Fannie Merritt (1904). Food and Cookery for the Sick and Convalescent. Boston, MA: Little, Brown & Co.

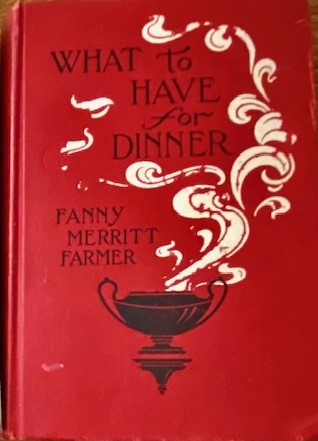

- Farmer, Fannie Merritt (1905). What to Have for Dinner: Containing Menus with Recipes for their Preparation. New York, NY: Dodge Publishing Company.

- Farmer, Fannie Merritt (1911). Catering for Special Occasions, with Menus and Recipes. Philadelphia, PA: D. McKay.

- Farmer, Fannie Merritt (1912). A New Book of Cookery: Eight-hundred and Sixty Recipes Covering the Whole Range of Cookery. Boston, MA: Little, Brown, and Company.

- Farmer, Fannie Merritt, ed. (1913). The Priscilla Cook Book for Everyday Housekeepers. Boston, MA: The Priscilla Publishing Company.

- Farmer, Fannie Merritt (1914). A Book of Good Dinners for My Friend; or “What to Have for Dinner”. New York, NY: Dodge Publishing Company.

- [Republication of What to Have for Dinner: Containing Menus with Recipes for their Preparation (1905).]

One hundred and three years after her death The New York Times published a belated obituary for Fannie Merritt Farmer. This obituary and Wikipedia are the primary sources used for this blog. I finally found a biography for her, but I don’t have it and don’t know how comprehensive it is.

Bottom line: People should know that Fannie Merritt Farmer was more than a compiler—or even a creator—of recipes.

For other extraordinary women I’ve highlighted on my blog, check out

- Trailblazing women in history

- The history of women in the workplace

- Notable women in psychological history

- Pioneering women in the music industry

- The struggle for women’s suffrage

- Religious historian Elaine Pagels

- Science fiction author Ursula K. LeGuin

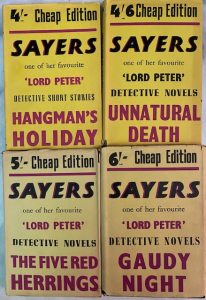

- Mystery author Dorothy Sayer

- Interviews with author Fiona Quinn and astronomer Heidi Hammel

- My paternal grandmother Margaret Louisa Butcher