Source” UNESCO Science Report towards 2030 data from UNESCO Institute for Statistics

Like so many professions, psychology has been male-dominated. Asked to name a psychologist, men like B. F. Skinner, John B. Watson, Stanley Milgram, and Sigmund Freud are likely to be mentioned —even though Freud was actually a medical doctor who founded psychoanalysis. But many of the most important movers and shakers in psychology were women. Here—in no particular order—is a brief introduction to just a few of them. I’m not including references; they are available on line in many forms.

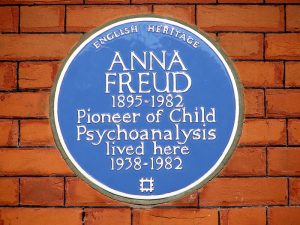

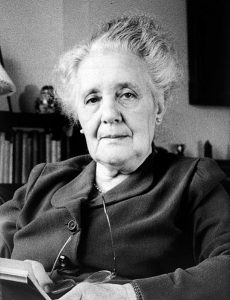

Anna Freud

(3 December 1895 – 9 October 1982)

Anna Freud was born in Vienna, the sixth and youngest child of Sigmund Freud and Martha Bernays. She is reported to have had an unhappy childhood, and she did not have a close relationship with her mother. Her older sister Sophie was the family beauty; Anna the one with brains. She may have suffered from depression, and she went to health farms to rest, exercise, and gain weight, implying eating disorders. At the same time, Anna was a lively child with a reputation for mischief.

Contrary to other members of her family, she had a close relationship with her father—something both of the psychoanalytic Freuds must have had thoughts about! Anna made good progress in most subjects, apparently mastering English and French and basic Italian easily.

Anna left her teaching career to care for her father. Sigmund Freud was diagnosed with cancer of the jaw in 1923. He underwent many operations and required long-term nursing assistance, which Anna provided. She also acted as his secretary and spokesperson, notably at the bi-annual congresses of the International Psychoanalytical Association, which her father was unable to attend.

Ultimately, she followed in her father’s footsteps into psychoanalysis. Alongside Hermine Hug-Hellmuth and Melanie Klein, Anna Freud may be considered the founder of psychoanalytic child psychology. She is credited with expanding interest in child psychology.

Anna expanded on her father’s work. Although Sigmund Freud recognized the id, ego, and superego, Anna’s work emphasized the importance of the ego. Among her many accomplishments, my favorite is her development the concept of defense mechanisms.

Anna Freud never married. Her only partner of record (as far as I know) was Dorothy Burlingham.

Mary Salter Ainsworth

(December 1, 1913 – March 21, 1999)

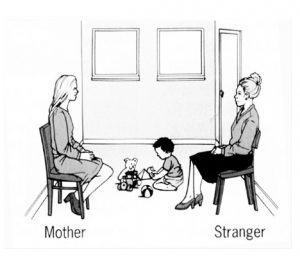

Mary Dinsmore Salter Ainsworth was an American-Canadian feminist, army veteran, and developmental psychologist who specialized in child psychology. Ainsworth devised an experiment called the “Strange Situation” in reaction to John Bowlby’s initial finding that infants form an emotional bond to its caregiver.

In Ainsworth’s experiments, the infant was placed in scenarios with or without the mother as well as with or without a stranger. The child’s behavior was observed in these “anxious” conditions. Ainsworth stated that infants react in 4 different attachment patterns (secure, ambivalent, avoidant, or disorganized) based on the extent of their bond to their primary caregiver.

The eldest of three daughters, Mary Dinsmore Salter was born in Ohio to Mary and Charles Salter. Although he possessed a master’s degree in history, her father worked at a manufacturing firm in Cincinnati. Her mother, who was trained as a nurse, was a homemaker. Both valued education highly. In 1918, her father’s manufacturing firm transferred him to Toronto, Ontario, Canada, where Salter spent the rest of her childhood.

Salter was a precocious child. She began reading by the age of three. Similarly to Anna Freud, she was close with her father, who tucked her in at night and sang to her. Also like Anna Freud, Salter did not have a warm relationship with her mother.

Mary Salter excelled in school, and decided to become a psychologist at the age of 15. She began classes at the University of Toronto at age 16, where she was one of only five students admitted to the honors course in psychology. She earned her bachelor’s degree in 1935, her master’s degree in 1936, and her PhD in 1939, all at the University of Toronto.

Salter’s dissertation, “An Evaluation of Adjustment Based on the Concept of Security,” shaped her subsequent professional interest. Her dissertation stated that “where family security is lacking, the individual is handicapped by the lack of a secure base from which to work.”

In 1942, Salter left teaching to join the Canadian Women’s Army Corps. She left the military in 1945 with the rank of Major. She married Leonard Ainsworth, a graduate student in psychology, in 1950. They divorced in 1960.

While working at Johns Hopkins, Ainsworth did not receive the proper treatment considering her skills and expertise: she was paid less and had to wait two years for an associate professor position even though her qualifications surpassed the job description. At the time, women and men had to eat in separate dining rooms, which ultimately meant women could not meet powerful male faculty members in the same informal way men could.

She eventually settled at the University of Virginia in 1975, where she remained until her retirement in 1984. As a professor emerita she remained active 1992.

Ainsworth received many honors, including the G. Stanley Hall Award from APA for developmental psychology in 1984, the Award for Distinguished Contributions to Child Development in 1985, and the Distinguished Scientific Contribution Award from the American Psychological Association in 1989. She was elected a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1992. She died of a stroke on March 21, 1999 at the age of eighty-five.

Mamie Phipps Clark

(April 18, 1917 – August 11, 1983)

Mamie Phipps was born in Hot Springs, Arkansas and died of cancer in New York City in 1983. She was the first Black woman to earn a degree from Columbia University, and the second Black student to earn a doctorate (after her husband Kenneth).

She entered Howard University in 1934 to study math and physics. While still an undergrad, she met her future husband. Kenneth Clark was a master’s student in psychology and urged her to switch to psychology. Both her B.A. and M.A. degrees were from Howard. After graduating magna cum laude, she worked in a law office for a time before matriculating at Columbia. Before graduating in 1943, she had had two children!

While working as a testing psychologist at an organization for homeless Black girls, Clark noted how limited mental health services were for minority children. In 1946, Clark and her husband founded the Northside Center for Child Development, which was the first agency to offer psychological services to children and families living in the Harlem area of New York City. Mamie Clark served as the Northside Center’s director until her retirement in 1979.

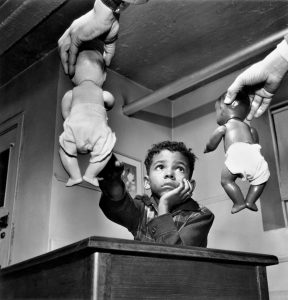

In her now-classic experiment, the Clarks showed Black children two identical dolls, one Caucasian and one Black. The children were then asked a series of questions including which doll they preferred to play with, which doll was a “nice” doll, which one was a “bad doll,” and which one looked most like the child.

The researchers discovered that not only would 59% the children identify the Black doll as the “bad” one, nearly 33% selected the white doll as the one they most resembled. Her research was central to demonstrating that separate is not equal.

Yes, she faced prejudice based on both her race and sex, but she went on to become an influential psychologist. She developed the Clark Doll Test as a tool for her research on racial identity and self-esteem. Her research on self-concept among minorities was ground-breaking. She played a role in the famous 1954 Brown vs. Board of Education case.

Clark’s work on racial discrimination and stereotypes were important contributions to developmental psychology and the psychology of race. Her effort on the identity and self-esteem of Blacks expanded the work on identity development.

Clark is not as famous as her husband. It has been noted that she adhered to feminine expectations of the time and often took care to “remain in the shadows of her husband’s limelight.” She often seemed shy. She achieved professional success while maintaining a fulfilling home life. She received a Candace Award for Humanitarianism from the National Coalition of 100 Black Women in 1983.

Leta Stetter Hollingworth

(May 25, 1886 – November 27, 1939, of abdominal cancer)

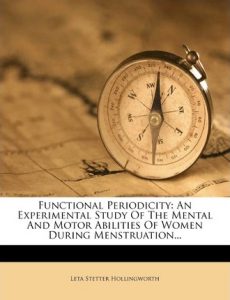

An early pioneer in U.S. psychology, Leta Stetter Hollingworth made her mark by her research on intelligence testing and giftedness. In particular, contrary to her contemporaries beliefs in genetic determination, she believed that education and environment were important factors.

Important as that work was, I admire her especially for her research on the psychology of women! At the time, women were believed to be inferior to men, and their intellect and emotions were at the mercy of their menstrual cycle. Hollingworth’s research demonstrated that women are as intelligent and capable as men, no matter where they are in their monthly cycles.

When her mother died giving birth to her third child, her father abandoned the family. The children were reared by their mother’s parents for a decade, until her father reclaimed the children and forced them to live with him and his new wife. Stetter later described the household as abusive, plagued by alcoholism and emotional abuse. Her education became a source of refuge.

Stetter left home when she graduated high school in 1902, at the age of 16, and enrolled at the University of Nebraska at Lincoln. Leta completed her bachelor’s degree and teaching certificate in 1906 and married Harry Hollingworth in 1908. She moved to New York so that her husband could pursue his doctoral studies. Originally she planned to continue teaching, but New York did not allow married women to teach high school at that time!

As a prime example of “when life gives you lemons, make lemonade,” she enrolled at Columbia University and earned a master’s in education in 1913. Leta Hollingsworth took a position at the Clearing House for Mental Defectives where she administered and scored Binet intelligence tests (testing for IQ). She completed her Ph.D. in 1916 and took a job at Columbia’s Teachers College, where she remained for the rest of her career.

She is also known for her work in the first two decades of the twentieth century that contributed in a small way to changing the views toward women that led to women having the right to vote in a nation that had too long denied them that right. One of her students who became well known is Carl Rogers.

Although she died at age 53, her influence on psychology has been impressive.

Melanie Klein

(30 March 1882-22 September 1960)

Melanie Klein was a psychoanalyst who was pivotal in developing play therapy. Working with children, she observed that they often utilize play as one of their primary means of communication. Play therapy is commonly used today to help children express their feelings and experiences. Young children aren’t able to participate in some of the more commonly used Freudian techniques, such as free association. Klein used play as a way to study children’s unconscious feelings, anxieties, and experiences.

Note: This was a major disagreement with Anna Freud, who believed younger children could not be psychoanalyzed. Today, Kleinian psychoanalysis is one of the major schools of thought within the field of psychoanalysis.

At the age of 21 Melanie Reizes married an industrial chemist, Arthur Klein, and soon after gave birth to their first child; subsequently, she had 4 more children. She suffered from clinical depression, and these pregnancies taking quite a toll on her. This and her unhappy marriage led Klein to seek treatment. She began a course of therapy with psychoanalyst Sándor Ferenczi, during which she expressed interest in studying psychoanalysis.

In 1921, Klein moved to Berlin and joined the Berlin Psycho-Analytic Society under the tutelage of Karl Abraham. Even with Abraham’s support for her pioneering work with children, neither Klein nor her ideas received general support in Berlin. As a divorced woman who did not even hold a bachelor’s degree, Klein was a clear outsider within a profession dominated by male physicians. Nevertheless, Klein’s early work had a strong influence on the developing theories and techniques of psychology.

As I said in the beginning, these are just a few examples of women who deserve more recognition and credit. There are many.

For example, Mary Whiton Calkins attended Harvard without being formally admitted. Although she had completed all of the requirements for a doctorate, Harvard refused to grant her the degree on the grounds that she was a woman. Even so, she became the first female president of the American Psychological Association in 1905.

Similarly, Christine Ladd-Franklin studied at John Hopkins and completed a dissertation, but the school did not grant women Ph.D.s at the time. Finally, in 1926, nearly 44 years after completing her degree work, John Hopkins awarded her a doctorate.

Bottom line: Choose any profession that interests you, look for members who made significant contributions to that profession but are under appreciated, and you will find women!

Editor’s Note: One of the reasons women are under appreciated for their work is that they are missing from the historical record. To correct that problem, Suw Charman-Anderson declared the second Tuesday of every October to be Ada Lovelace Day, an opportunity to raise the profiles of women in STEM fields. One of the ways everyone can participate is by creating or improving the Wikipedia pages of significant women who are not as well-known as they should be.