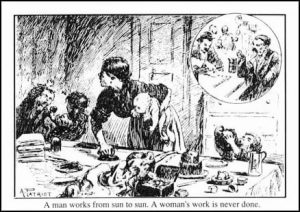

First the rant: When I started researching this blog, all I found was a history of paid employment. I’m not alone in bemoaning the fact that women’s household contributions, care for household members, kitchen gardens, work on family farms, etc. is largely discounted, and vastly undervalued!

According to Investopedia, in 2019, Salary.com put a dollar value on the work of a stay-at-home-parent. Depending on the size of the house, family, pets, and numerous other conditions, a stay-at-home parent may work upwards of 96 hours per week, providing services worth a median annual salary of $178,201!

Analysis from Oxfam in 2020 reported on stay-at-home women (who still outnumber men) doing unpaid labor in the U.S. Using minimum wage per hour for its calculations, their unpaid labor in 2019 was worth $1.5 trillion.

Unfortunately, no matter how valuable the unpaid labor, it remains unpaid. When women enter the paid labor force, the job is typically in addition to the unpaid labor.

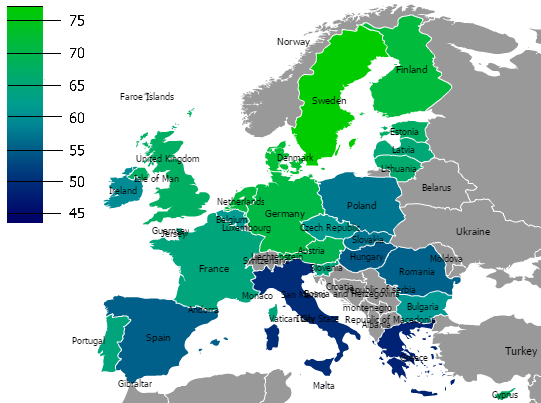

In 2018, 57.1 percent of all women participated in the labor force. This was about the same as the 57.0 percent who participated in 2017, and about 3 percentage points below the peak of 60.0 percent in 1999.

In 2019, there were 76,852,000 women aged 16 and over in the labor force, representing close to half (47.0%) of the total labor force. 57.4% of women participated in the labor force, compared to 69.2% of men.

Women are now making 83% of what men earn for the same job. (The gap is even wider for women of African or Latin American heritage.) This isn’t a perfect number, but it is improving — thanks to women in the workforce.

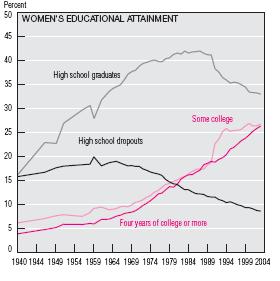

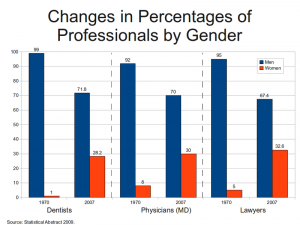

By striving to obtain more education, women have a better chance of finding jobs, getting better opportunities and entering fields that were previously male-dominated.

Women in the labor force: a databook : BLS Reports: U.S. …

19th Century

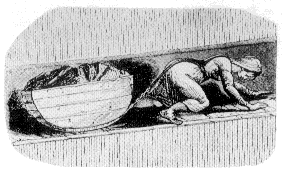

“The Industrial Revolution of the late 18th and early 19th centuries changed the nature of work in Europe and other countries of the Western world. Working for a wage, and eventually a salary, became part of urban life. Initially, women were to be found doing even the hardest physical labor, including working as “hurriers” hauling heavy coal carts through mine shafts in Great Britain, a job that also employed many children.”

Wikipedia, Women in the workforce.

During the 19th century, the number of women working in factories drastically increased. Prior to the Industrial Revolution, the most common form of employment for women in Europe and North America was piecework, which involved needlework (weaving, embroidery, winding wool or silk) that paid by the piece completed. It was poorly paid and involved long hours, up to 14 hours per day to earn enough wages to survive.

According to the 7th Earl of Shaftsbury, employers often preferred to hire women, because they could be “more easily induced to undergo severe bodily fatigue than men.” Pregnant women worked up until the day they gave birth and returned to work as soon as they were physically able. In particular, employers liked to hire married women: “They are attentive, docile, more so than unmarried females, and are compelled to use their utmost exertions to procure the necessaries of life.”

The 1870 US Census was the first to count “females engaged in each occupation” and provides a snapshot of women’s history in the workplace. Women workers showed up in interesting places. The majority of women working outside the home held typically “feminine” positions, such as childcare, dress-making, millinery, and tailoring. Two-thirds of teachers were women.

Women were 15% of the total work force (1.8 million out of 12.5). They made up one-third of factory “operatives.” Women could also be found in relatively unexpected places.

- Iron and Steel Works (495)

- Mines (46)

- Sawmills (35)

- Oil Wells and Refineries (40)

- Gas Works (4)

- Charcoal Kilns (5)

- Ship Rigger (16)

- Teamster (196)

- Turpentine Laborer (185)

- Brass Founder/ Worker (102)

- Shingle and Lathe Maker (84)

- Stock-herder (45)

- Gun and Locksmith (33)

- Hunter and Trapper (2)

20th Century

Education was a major driver toward equality, both among the lower classes and for girls in particular. At the turn of the 20th century, attitudes towards educating girls were changing. Women in North America and Western Europe were more educated, largely due to the efforts of women to further their own education, defying opposition by male educators.

Many women organized “dame schools” for local children, teaching elementary literacy and arithmetic to students who probably would not have learned otherwise.

By 1900, four out of five colleges accepted women and the concept of coed education was becoming more accepted.

In the United States, the rise in demand for production from Europe during World War I (among other economical and social influences) facilitated the entry of women into the workforce.

In the first quarter of the century, women mostly occupied jobs in factory work or as domestic servants, but as the war came to an end they moved on to other jobs: salespeople in department stores, clerical, secretarial, and other so-called, “lace-collar” jobs. Broadening telegraph and telephone networks provided appropriately ladylike work in operation centers.

Towards the end of the 1920s, married women exited the work force less often. Labor force productivity for married women 35–44 years of age increased from 10% to 25%. There was a greater demand for clerical positions and, as the number of women graduating high school increased, they began to hold more “respectable,” steady jobs.

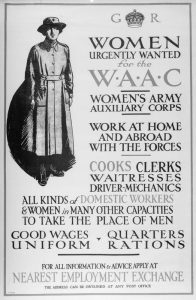

World War II created millions of jobs for women.

Thousands of American women joined the military:

- 140,000 in the Women’s Army Corps (United States Army) WAC

- 100,000 in the Navy (WAVE)

- 23,000 in the Marines

- 14,000 in the Navy Nurse Corps

- 13,000 in the Coast Guard

Although almost none of the women in the military saw combat, they replaced men in noncombat positions and got the same pay as the men would have on the same job!

One of the most interesting (and often overlooked) units of the US military during World War II was the 6888th Central Postal Directory Battalion. It was the only all-female, all-African American Army unit. The “Six Triple-Eights” was an entirely self-contained unit, not attached to any male unit. Major Charity Adams led her troops to the European Theater of Operations (being bombed twice just getting there) to sort the problem of years’ worth of mail sent to the front. The 6888th Battalion was given six months to sort out and deliver the warehouses full of letters and parcels that had been untouched for more than two years; they had everything sorted in three.

As 16 million men left their jobs to join the war in Europe and elsewhere, even more opportunities emerged for women to join the job force.

Although two million women lost their jobs after the war ended, female participation in the workforce was still higher than it had ever been. In post-war America, women were expected to return to private life as homemakers and child-rearers.

Nevertheless, jobs were still available to women.

They were mostly what are known as “pink-collar” jobs such as retail clerks and secretaries.

The Quiet Revolution

Transition Era refers to the time between 1930 and 1950, when the discriminatory institution of marriage bars—which forced women out of the work force after marriage—were eliminated. Additionally, women’s labor force participation increased because there was an increase in demand for office workers. However, women did not normally work to fulfill a personal need for a fulfilling career or social worth; they worked out of necessity.

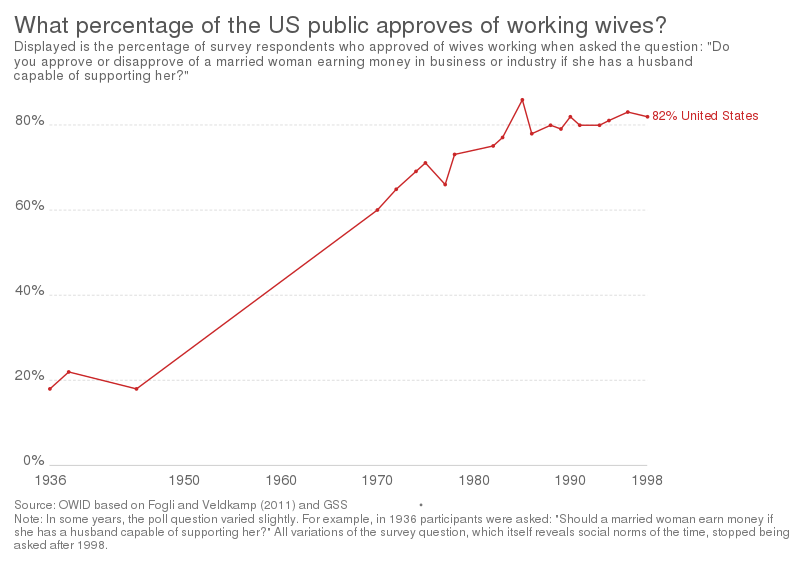

From 1950 to mid-to-late 1970s, the movement of women into the workforce began to show signs of a revolution. Women’s expectations of future employment changed. They began to see themselves going on to college and working through their marriages, even attending graduate school.

Many had brief and intermittent work force participation, without necessarily having expectations for a “career.” Most women were secondary earners, and worked in “pink-collar jobs” as secretaries, teachers, nurses, and librarians.

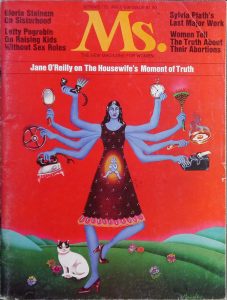

The sexual harassment experienced by these pink collar workers is depicted in the film 9 to 5. Nevertheless, labor force participation by women still grew significantly.

The fourth phase of the “Quiet Revolution” began in the late 1970s and continues today. Beginning in the 1970s women began to flood colleges and grad schools. They began to enter profession like medicine, law, dental, and business. More women were going to college and expected to be employed at age 35, as opposed to past generations that only worked intermittently due to marriage and childbirth. These women defined themselves prior to a serious relationship.

Research indicates that from 1965 to 2002, the increase in women’s labor force participation more than offset the decline for men.

Some scholars have attributed this big jump in the 1970s to widespread access to birth control pills. While “the pill” was medically available in the 1960s, numerous laws restricted access to it. By the 1970s, the age of majority had been lowered from 21 to 18 in the United States (largely as a consequence of the Vietnam War), which affected women’s right to make their own medical decisions.

Since it had become socially acceptable to postpone pregnancy even while married, women had the option of pursuing education and work.

Also, due to various labor-saving devices, women’s work around the house became easier leaving with more time to pursue school or work. Due to the multiplier effect, even if some women were not blessed with access to the pill or , many followed by the example of the other women who entered the work force for those reasons.

The Quiet Revolution is called such because it was not a “big bang” revolution; rather, it happened and is continuing to happen gradually.

Still Not a Bed of Roses

Working women get carpal tunnel syndrome, tendonitis, anxiety disorders, stress, respiratory diseases, and infectious diseases due to their work at higher rates than men. Women’s higher rates of job-related stress may be due to the fact that women are often caregivers at home and do contingent work and gig work at a much higher rate than men.

Another significant occupational hazard for women is homicide, which was the second most frequent cause of death on the job for women in 2011, making up 26% of workplace deaths in women.

Nevertheless, women are at lower risk for work-related death than men, probably (at least partially) due to their lower proportion of workers in certain high-risk job such as lumberjacks and garbage collectors.

Even so, personal protective equipment is usually designed for typical male proportions, which can create hazards for women who have ill-fitting equipment.

Immigrant women are at higher risk for occupational injury than native-born women in the United States, due to higher rates of employment in dangerous industries.

Sexual harassment is an occupational hazard for many women, and can cause problems including anxiety, depression, nausea, headache, insomnia, feelings of low self-esteem and alienation.

Women overall are at higher risk for occupational stress, which can be exacerbate by balancing roles as a parent or caregiver with work.

Many job opportunities for women are still limited. For example, skilled workers who train by getting apprenticeships with certified professionals (such as electricians or plumbers) include few women—and these are high paying jobs.

Bottom Line: The history of women’s work is still being written.

Very interesting! Readers may be interested in an in-depth look at the lives of young, mostly single, frequently immigrant woman working in clothing factories in the book “Triangle : The Fire That Changed America” by David von Drehle. Also, O Henry wrote many insightful short stories about the lives of single woman living in the early 1900’s. But these suggestions are only in addition to your thoroughly researched blog – thanks!