(Richard III, 4.4.149)

Toads have had a bad rap in the west. At least as far back as Shakespeare the toad’s ugliness had become a synonym for anything loathsome. And then there is the poisonous nature of toads. Could anything so repulsive and toxic not be evil? And let’s not forget the association of toads with witchcraft, and even Satan himself.

On the other hand, according to Robert DeGraaff (The Book of the Toad), “There is a great deal of evidence that in early Asiatic cultures and in the pre-Columbian civilizations of the Americas the toad was regarded as a divinity, the great primeval Earth Mother, the source and end of all life.”

Today, there is evidence that reality falls somewhere in between.

All toads have toxic substances in the skin and parotid glands. Ingestion of toads or toad cake (i.e., the dried secretions) can lead to intoxication. They secrete one or more of five compounds: bufotoxin, bufotenin, 5-MeO-DMT, bufotalin, and bufalitoxin.

Most toxic compounds of these toxin are steroids similar to digoxin. Patients who have inadvertently ingested toad toxins usually have gastrointestinal symptoms consisting of nausea, vomiting, and abdominal discomfort.

Toad secretions and cake have been used as a drug for its cardiotonic, anti-inflammatory, and analgesic (pain relief) effects since ancient times. Doctors in China have used Bufo genus toad cake dissolved in water to treat heart disease and slow the spread of cancerous cells for centuries.

The mild poison of most toads in the U.S. is not lethal to humans, but it can cause allergic reactions. It is important to wash your hands after touching a toad.

Toads are not venomous. They secrete toxins rather than injecting it.

Two Poisonous Toads in the U.S.

The glands of American toads secrete bufotoxin, a poisonous substance meant to make the toad unpalatable to potential predators. Although most toads in the United States are only mildly toxic, their secretions can cause serious damage when smaller pets (such as dogs or cats) eat one of these toad varieties.

I’m going into some detail here because these two species pose a real danger as opposed being a nuisance or discomfort, like most toads in this country.

FYI, the most poisonous toad in the world is the golden poison frog (Phyllobates terribilis), also known as the golden dart frog or golden poison arrow frog, is a poison dart frog endemic to the rainforests of Colombia. Think curare.

Avoiding toads is relatively easy for most of us: they are nocturnal, and they hibernate underground during cold weather.

There is no specific antidote for toad toxins, so pay attention!

Rhinella marina (Cane Toad)

Cane toads’ native stomping ground ranges from to the Amazon basin in South America all the way north to the lower Rio Grande Valley in southern Texas. They have established habitats in Florida, Hawaii, Puerto Rico, U.S. Virgin Islands, Guam (including Cocos Island) and Northern Mariana Islands, American Samoa, and Republic of Palau. In Australia, where farmers originally introduced them to help control scarabs eating sugarcane, cane toads have become one of the worst invasive species in the world.

The skin-gland secretions of cane toads (bufotoxin and bufotenin) are highly toxic and can sicken or even kill animals that bite or feed on them, including native animals and domestic pets.

When swallowed, cane toad toxin can affect the heart and central nervous system. People may experience blood pressure swings, breathing problems, paralysis, seizures, salivation, twitching, vomiting, and crying. Adult cane toads can secrete enough toxin to kill a small child. In severe cases. exposure can cause death through cardiac arrest, sometimes within 15 minutes. At the least, the skin secretions irritate the skin or burn the eyes of people who handle them.

Humans can also use this toxin as a weapon. The Emberá and Wounaan people of Panama have traditionally used Cane Toad toxins on the tips of their arrows.

The prevalence of a toxin resistance gene makes it possible for some snakes of the sub-family Natricinae to consume native toads. In a 2021 article from the Journal of North American Herpetology, researchers Jordan Donini and Sean Doody said, “We documented successful consumption of the invasive cane toad by the Southern Watersnake (Nerodia fasciata) in southwest Florida, both in the wild and in the laboratory.”

Depending on where you live/travel, it can be important to know the difference between a cane toad and a native southern toad (Anaxyrus terrestris). Adult cane toads are much larger than adult southern toads, which only grow to a maximum of approximately 3 to 4 inches. Cane toads do not have ridges across the head, as seen in the southern toad.

Cane Toad Appearance:

- Tan to reddish-brown, dark brown or gray

- Creamy yellow belly

- 4”-6” long (sometimes 9 inches)

- Backs are marked with dark spots

- Warty skin

- Triangular parotoid glands on shoulders that secrete a milky toxin substance (native southern toads have oval glands)

- No ridges on top of head unlike native southern toad

Incilius alvarius (Sonoran Desert Toad)

The Sonoran Desert Toad – previously known as the Colorado River Toad – is native to the United States and Northwestern Mexico. Like the Cane Toad, the Sonoran Desert Toad secretes bufotoxins that can seriously injure humans and kill smaller animals such as dogs.

Their native habitat in the US includes Arizona, New Mexico (where they are a threatened species), and California (where they are a species of special concern). Because these toads are native, they cannot be legally killed in those areas. That hasn’t stopped people from trying to harvest their toxins.

Sonoran Desert Toad appearance:

- Olive green to dark brown color

- Belly is cream colored

- 3”-7” long

- Smooth and shiny skin, but warty

- Distinctive oval glands behind each eye

- Visible glands on their hind legs

Psychedelic Toads

In 2022, the National Park Service had to issue a blanket warning to visitors not to lick wildlife, especially toads. The toxins that some toads secrete can (under specific circumstances) cause psychedelic hallucinations.

The smoke from dried toad cake of both Cane Toads and Sonoran Desert River Toads causes hallucinations. Licking a toad will likely just cause extreme discomfort for both yourself and the toad.

Cane Toad secretions contain bufotenine, a tryptamine that can have hallucinogenic effects in large enough doses. Several religious traditions have used this toxin for ceremonial purposes. The Olmec obtained bufotenine by milking toads over hot rocks and then using the toxin as a narcotic. Chemical analysis of seven Haitian “zombie powders” found secretion glands from Cane Toads, along with puffer fish and hyla tree frogs.

Sonoran Desert toads secrete an enzyme known as O-methyl-transferase, which converts bufotenine into the extremely potent psychedelic 5-MeO-DMT. When a human inhales smoke from 5-MeO-DMT, they experience hallucinations many have called “religious.” Researchers are developing treatments for depression, anxiety, and addiction from the psychedelic properties of Sonoran Desert toad secretions. Dr. Alan K. Davis, a clinical psychologist at Johns Hopkins University warns, “It’s such an intense experience that, in most cases, doing it at a party isn’t safe. It’s not a recreational drug. If people get dosed too high, they can ‘white out’ and disassociate from their mind and body.”

Ingesting Sonoran Desert Toad toxin orally does not cause hallucinations, but that hasn’t stopped people from trying. According to the National Poison Center, “Licking toads (typically cane toads) can be dangerous, however, and may cause muscle weakness, rapid heart rate, and vomiting.”

The Toad Pharmacy

All Bufo species of toads have parotid glands that release toxic substances when the animals are threatened. These toxic substances are biologically active compounds, such as dopamine, norepinephrine, epinephrine, serotonin, bufotenine, bufogenin, bufotoxins, and indolealkylamines. You might notice that the first four listed here are familiar!

In “The Development of Toad Toxins as Potential Therapeutic Agents” by Ji Qi, Abu Hasanat Zulfiker, Chun Li, David Good, and Ming Q. Wei, the authors make the following points:

- In traditional Chinese medicine (TCM), processed toad toxins have been used for treating various diseases for hundreds of years. Modern studies have revealed the molecular mechanisms that support the development of these components into medicines for the treatment of inflammatory diseases and cancers.

- Recently there have been studies that demonstrated the therapeutic potential of toxins from other species of toads, such as Australian cane toads.

- Toxins from toads have long been known to contain rich chemicals with great pharmaceutical potential. Recent studies have shown more than 100 such chemical components, including peptides, steroids, indole alkaloids, bufogargarizanines, organic acids, and others, in the parotoid and skins gland secretions from different species of toads.

Frogs or Toads?

Many people confuse frogs and toads. After all, they are biologically related and share many characteristics. Scientifically, frogs and toads belong to the same taxonomical group. Both have glandular skin and similar diets, which they swallow whole. Additionally, both are amphibians and periodically shed their skin.

| Toads | Frogs |

|---|---|

| Live on land | Live near water |

| Warty-looking skin | Sleek, smooth skin |

| Dry skin | Mucus-covered skin looks wet even when dry |

| Short legs | Legs longer than head and body |

| Get around by crawling | Hop instead of crawl |

| Broad, flat nose | Pointed nose |

| Spawn in chains | Spawn in gooey clumps |

| Solid black, round shaped tadpoles | Gold-flecked, slim shaped tadpoles |

Toad Miscellany

Among amphibians, the anurans, or frogs and toads, are perhaps the most intelligent, and have the largest brain-to-body ratio of the amphibians.

By and large, the brighter the toad’s coloration, the more toxic it is.

American toads hibernate during the winter. They will usually dig backwards and bury themselves in the dirt of their summer home. However, they may also overwinter in another area nearby.

You can find toads in all but the coldest parts of the world.

Adult toads eat insects, snails, slugs and earthworms.

Toads do not drink water. Instead, they absorb it through their skin.

Despite spending most of its life on land, a toad will return to the water during the mating season. They lay their eggs in water.

Being carnivores, toads prefer eating live meat. They do not consume dead meat or previously killed animals. Technically, they are able to consume fruits and vegetables, but it might not make them happy.

A toad will also eat its own skin after shedding it. However, they do this to hide from predators rather than for any nutritional value.

Toads live approximately 5-10 years in the wild. However, a toad in captivity can live up to 40 years.

Collective nouns for a group of toads includes a knot, nest, array, knob, knab, lump, and squiggle.

Toads can carry salmonella, which they can transfer to humans or other animals handling them.

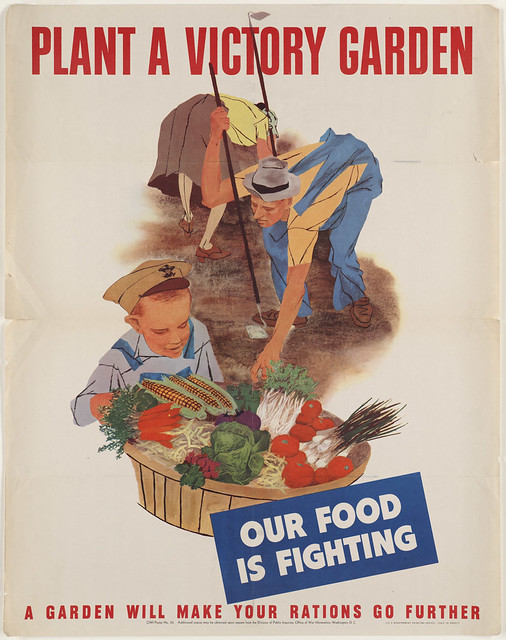

Toads are great additions to any garden because they eat the pests that may plague the plants—and the gardeners.

Bottom Line: Better know toads!