“Trump has several verbal tics. One is that when he’s trying to flatter and finagle, everything is beautiful: countries, cities, people, bills, questions, even chocolate cake.” This sentence from a New York Times op-ed piece by Charles M. Blow (July 17, 2017) brings to the fore both the use and abuse of verbal tics.

Thank you Arizona. Beautiful turnout of 15,000 in Phoenix tonight! Full coverage of rally via my Facebook at: https://t.co/s0D12EFs40 pic.twitter.com/WT4D9Vsen1

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) August 23, 2017

Trump’s use of “beautiful” is abuse in two ways. First, any word or phrase used frequently and indiscriminately becomes meaningless. The listener/reader quickly realizes that it comes from habit, not thought. Writers should be aware that besides being meaningless, such repetition—particularly in narrative—is boring.

Second, any word as vague as beautiful—or ugly, dreadful, lovely, disgusting, frightening, etc—tells the listener/reader a reaction, but not the reason for it. For writers, the lesson here is that such vagueness doesn’t engage the reader. To do that, be specific: describe what your character is seeing, hearing, etc., that caused the conclusion. Often, it’s best to drop the conclusion altogether and let the reader react.

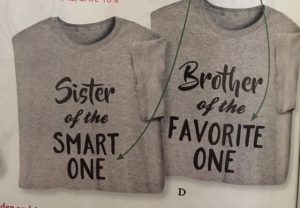

And what about the use of verbal ticks? I can think of only one: they are great character notes. Depending upon the repeated word or phrase, they can convey education level, social class, and even age. Consider the impact of “precisely” versus “golly gee.”

People use only a tiny fraction of the vocabulary they comprehend. Everyone has verbal habits, including tics. I have to be aware not to overuse the word “great.” As a writer, be aware of your favorite words and use them sparingly! That’s where a good thesaurus comes in.