Very few people wear no jewelry at all, at any time. That said, men are more likely than women to be among those few. Where, when, and what type of adornment provide fertile ground.

Characters from different cultural backgrounds, time periods, and social classes are likely to view jewelry in ways that seem odd to outsiders.

So change it up!

Go Against Expectations

In June of 2020, I posted another blog about jewelry titled JEWELRY AS MORE THAN BEAUTIFICATION: IDENTIFICATION, INFORMATION, AFFILIATION, COMMUNICATION. Lots of good information there (I say, most humbly) but I won’t repeat it here.

In determining your characters’ jewelry profiles, start with “Why does this character wear (or not wear) jewelry?”

Uses of Jewelry

Jewelry is often viewed as a fashion accessory for complementing one’s clothes, especially for special occasions. With a bit of imagination, it can be so much more.

Research has shown that wearing jewelry can increase an individual’s self-esteem. Nursing home residents with memory loss were less unruly when they wore jewelry.

Not wearing jewelry when it is the norm can also attract attention, possibly criticism (such as removing a wedding ring before going out to drink).

Many wear jewelry as a symbol of femininity or masculinity. Think of the number of female athletes who wear jewelry while competing or even coaching. Think biker chains and skulls.

Jewelry has an obvious dollar value that can be a signifier, even if it is fake.

- Showcase social status or wealth

- Serve as an investment

- Be a safety net for financial independence

- This is especially common among women, particularly in nomadic cultures

Jewelry can make a person feel confident and attractive.

Jewelry can have personal or sentimental value. It can be a powerful connection to loved ones and memories.

Many wear jewelry because, well, one likes how it looks.

Wearing jewelry can be a way to express oneself.

- Red jewelry, for example, connotes vitality, courage, and confidence.

- Anchor jewelry denotes stability, strength, steadfastness, and hope.

- Hemp

A variety of jewelry pieces signify strength, courage, and hope. Some actually contain the word—in letters or Morse code.

The recorded sound wave of a loved one’s voice (or bark) can be etched onto the metal of a ring or pendant.

Others are symbolic like the Celtic tree of life, the Viking axe pendant, the Egyptian ankh, or the eagle ring. Still others could be more esoteric, like dragonfly earrings supporting the wearer to pursue dreams. These are often gifted or awarded to someone.

Jewelry for Healing or Health

One well-known example is the usual 7 stones in the chakra, used for reiki, healing, meditation, chakra balancing, or ritual:

- Amethyst (Crown Chakra)

- Carnelian (Sacral Chakra)

- Yellow Jade (Solar Plexus)

- Green Aventurine (Heart Chakra)

- Lapis Lazuli (Throat Chakra)

- Clear Crystal (Third-Eye Chakra)

- Red Jasper (Root Chakra)

Virtually every stone is associated with physical and/or mental health in one way or another. Whole books have been written about. One good all-around reference for The Book of Stones: Who they are & What They Teach by Robert Simmons & Naisha Ahsian.

Particular Stones in Jewelry

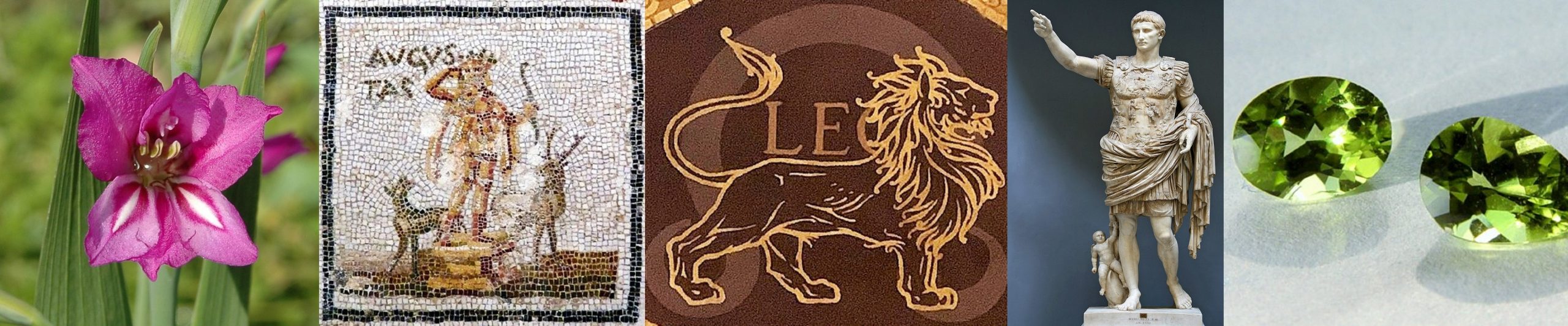

First of all, think birthstones.

Although there is assumed to be a particular affinity with one’s birthstone, there is no hard evidence (that I found) that this is the case. One thing they all have in common is that they sparkle, especially in sunlight. Some wearers find the sparkle both beautiful and cheering.

In general, does your character prefer sparkly stones, opaque ones, or no stones?

- As a general rule, sparkly stones are dressier as well as more expensive than opaque ones. Are these factors?

- Opaque stones offer more variety, from jasper to turquoise to onyx.

- Color and pattern are primary considerations.

Turqupise: An Example of How a Stone Can Be Related to a Character

John is an undercover police officer, 6’4” tall, and he wears silver jewelry as a statement that he’s a rogue, and not to be intimidated. Depending on the role he’s playing, he sometimes goes more subtle, choosing a tie bar, cufflinks, or belt buckle.

When he delved into turquoise, he discovered the huge range of colors, including copper-turquoise in blue, green, purple, red/orange, and black.

Women find him handsome and say his jewelry just accentuates that he’s one of a kind. He once dated a woman who told him turquoise represents wisdom, tranquility, protection, good fortune, and hope, and that contemporary crystal experts celebrate it for its representation of wisdom, tranquility, and protection. John is skeptical of all that.

His preference for turquoise reflects his (distant) connection to Native American culture, even though he has no involvement with a tribe and was reared entirely within the Anglo world. However, his paternal great-grandfather was Navajo. John has a blue turquoise ring that belonged to his great-grandfather, and a green turquoise one made by his great-grandfather’s brother.

When those rings came to John, he was surprised to learn that Native Americans (the Hohokam and Anasazi peoples) first started mining and using turquoise around 200 B.C.E. They mined the famous Cerrillos and Burro Mountains of what is now New Mexico and, in Arizona, the Kingman and Morenci turquoise mines.

When John is deep in thought, he often turns his ring around and around. Depending on context, he can do this when problem solving, daydreaming, or planning. He is very disciplined not to do it when playing poker or being threatened.

Which Metal

- Platinum

- Gold

- White gold

- Yellow gold

- Red gold

- Silver

- Aluminum

- Titanium

- Stainless steel…

Not to mention the role of leather, cord, wood, hemp… But I’m not going there!

When Not to Wear Jewelry

Many professions require specific jewelry or no jewelry at all. This could be for safety considerations or to create a specific professional impression.

- Most medical professionals cannot wear rings, bracelets, necklaces, or large earrings for health safety.

- Jobs requiring heavy machinery, blades, or high temperatures (locksmith, chef, welder, etc.) generally prohibit wearing anything that dangles or hangs.

Raw food can also get caught in the settings of rings and bracelets, trapping bacteria and other contaminants in your jewelry and leading to possible skin irritation or contaminated food.

While at the beach, the sun, sand, and sharks (attracted to shiny objects) are three reasons why not to wear jewelry at the beach.

Whenever the activity might damage or wear-down the gem or the metal. This list is just a reminder. You can figure out the risks associated with each activity for yourself—except, maybe, sleeping!

- Showering

- Swimming

- Whether in the pool or at the beach

- Exercising

- Cleaning

- Getting ready in the morning

- Gardening

- Cooking

- Sleeping

- Painting

Jewelry prongs/settings can wear down faster during sleep, especially if someone tosses and turns a lot. The prongs can also become bent out of shape if caught on a sheet or blanket, making the chances of accidentally losing a gemstone more likely.

Bottom line: Writers, tap the rich vein of jewelry and gemstones to add depth and detail to your work!