We all know about procrastination: doing less urgent/important things instead of more important/urgent ones—or doing more enjoyable tasks when less appealing tasks are more needful; deliberately looking for distraction from the task at hand. Virtually everyone procrastinates sometimes, and 20% of people are chronic procrastinators. Some people boast that they “work to deadlines,” often hustling or cramming at the last minute. Another catch-phrase is, “I work better under pressure.” Really?

We all know about procrastination: doing less urgent/important things instead of more important/urgent ones—or doing more enjoyable tasks when less appealing tasks are more needful; deliberately looking for distraction from the task at hand. Virtually everyone procrastinates sometimes, and 20% of people are chronic procrastinators. Some people boast that they “work to deadlines,” often hustling or cramming at the last minute. Another catch-phrase is, “I work better under pressure.” Really?

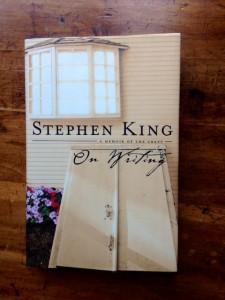

Some types of procrastination are common for writers: organizing the workspace and writing implements so thoroughly that the writing time’s compressed or obliterated; editing for the umpteenth time, so long that the piece is never really finished; immersing themselves in one more bit of research, perhaps going off on a tangent into something interesting, possibly useful for some other work in the future; even reading broadly for pleasure and muttering excuses that all reading is good for a writer. Let me be clear: organization, preparation, editing, research, and reading are not evil in and of themselves, only when they block actual forward movement in the manuscript.

Writers are people. And people suffer from procrastination. Late payment fees, lower grades, anger or disappointment from friends and family are immediate outcomes of some kinds of procrastination. But who cares if a writer puts off writing? If writing puts food on the table, it threatens livelihood. But whether that’s the case or no, not meeting one’s goals/commitments leads to guilt, depression, and low self-esteem.

According to one accessible source, Psychology Today, “procrastination reflects an on-gong struggle with self-control as well as an inability to know how we’ll feel tomorrow or the next day.” They have articles on everything from the history of procrastination to its relationship to morality, from ways to overcome procrastination to boredom at work. Some claim that procrastination is a defense mechanism against fear of failure: if the last-minute product isn’t perfect, the creator can take comfort in the knowledge that working on it more, it would have been better, could have been great. Then there is the positive side of procrastination: it reveals what one’s real motives and value are.

Takeaway one

Acknowledge whether/when/why you procrastinate in your writing life. Consider what that tells you about the importance of writing—for you.

Takeaway two

If writing is truly important, sweep aside the hurdles. Take baby steps—a page or two a day, no editing till there’s one complete draft. Don’t doubt yourself. Just do it. And if you need help with that, read all the on-line tips on overcoming procrastination. And if that doesn’t work, and you truly care, seek therapy. Help is out there.