Given the season, I was tempted to write about New Year’s resolutions. Not wanting to repeat myself, I reviewed my blogs from 12/30/16, 1/1/19, and 1/3/23. And then I realized that all sorts of commentators and media were talking about how many people make resolutions (between 34 and 62%), who makes them (younger people), how many people keep them (fewer than half), what the resolutions are about (fitness, finances)… I decided I have nothing to add this year.

In the meantime, the Wall Street Journal recently (Dec. 20-21, 2025 issue) had a long article about the Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary. I venture to suggest that when asked about a dictionary, that’s the one most people think of. For generations, a copy has been a go-to gift for high school and college graduates, as well as miscellaneous other gift-giving occasions. In the late 1980s, Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary was on the Times best-seller list for 155 consecutive weeks; 57 million copies were sold, a number believed to be second only to sales of the Bible in the U.S.

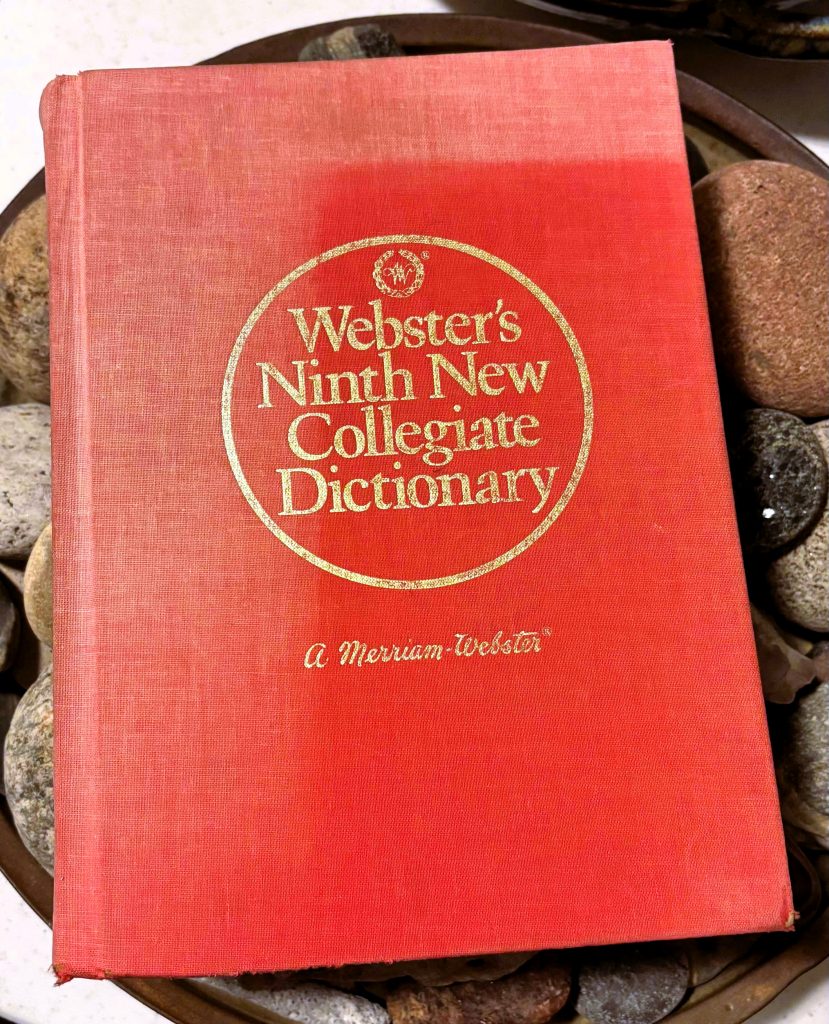

And people hold on to them! My husband still has one from his last year as an English professor, the 9th edition, published in 1983.

Partying with half a dozen other writers, I asked whether they still use physical dictionaries. NO! Not one. They all look online (as do I). Still, physical dictionaries haven’t yet gone the way of the dodo bird: last year Merriam-Webster sold nearly 1.5 million physical dictionaries (according to that WSJ article).

I love dictionaries, so I researched their history for this blog. They have a fascinating (to me) history that reflects the evolution of language, literacy, and knowledge organization.

Dictionary History

Dictionaries have had a long run!

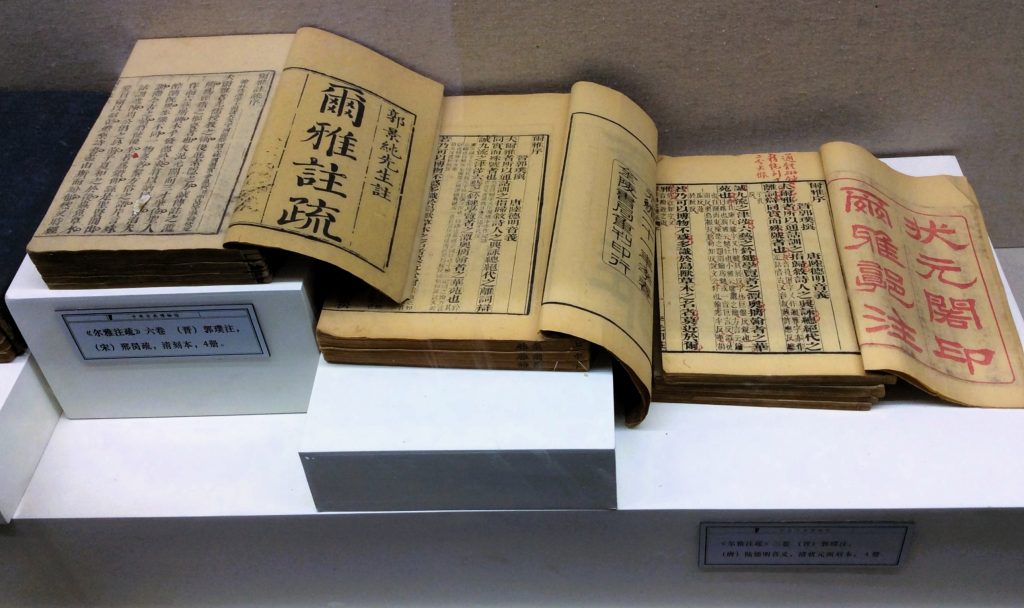

The earliest surviving monolingual dictionary is the Eyra, which Chinese scholars wrote in the 3rd century BCE. Translators have interpreted the title characters (爾雅) as “Progress Towards Correctness”, “The Semantic Approximator”, and “Approaching Elegance.”

Modern dictionaries evolved from early glossaries and bilingual word lists. Renaissance glossaries and later works like the Catholicon (1287) and Covarrubias’s Tesoro de la lengua (1611) paved the way for modern single-language dictionaries and standardized national lexicons. By the 18th–19th centuries, publishers were offering monolingual dictionaries, including comprehensive English dictionaries.

Early Beginnings

The earliest known attempts at word lists and glossaries date back to ancient Mesopotamia (around 2300 BCE). Scribes learning languages created Sumerian and Akkadian bilingual word lists.

Classical Antiquity

In ancient Greece and Rome, scholars compiled lists of difficult or rare words, often to assist with understanding classical texts. For example, Philo of Byblos and Aelius Donatus created early glossaries. Philitas of Cos wrote Disorderly Words to help his fellow Greeks decipher odd and archaic vocabulary, particularly in the works of Homer.

Medieval Period

During the Middle Ages, dictionaries were often glossaries—lists of difficult words with explanations—in Latin and vernacular languages. They were primarily tools for scholars and clergy.

The rise of vernacular languages in Europe led to more dictionaries aimed at explaining Latin terms or translating between Latin and local languages.

Renaissance and Early Modern Era

The invention of the printing press in the 15th century revolutionized dictionary production.

In 1604, Robert Cawdrey published the first English dictionary, titled A Table Alphabeticall, containing about 2,500 words with simple definitions.

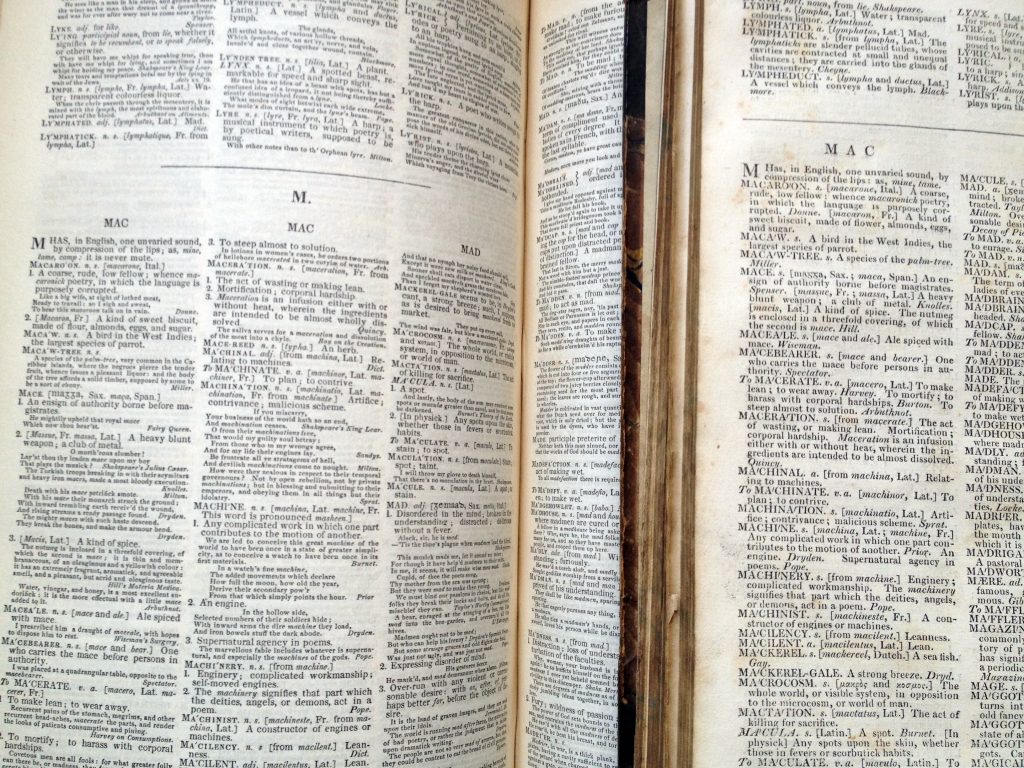

The 17th and 18th centuries saw the rise of more comprehensive dictionaries. Samuel Johnson’s Dictionary of the English Language (1755) was a landmark work, combining definitions with literary quotations and shaping English lexicography.

19th and 20th Centuries: The Oxford English Dictionary

Once upon a time, when asked what one book I’d want to have if stranded on a desert island, I didn’t even have to consider: “The Oxford English Dictionary, not in the condensed form.”

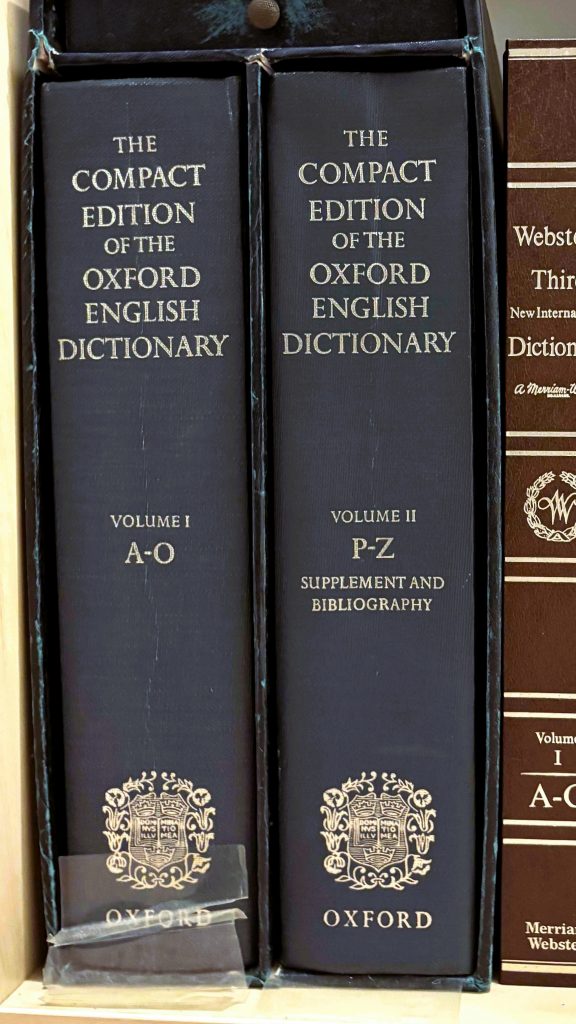

Actually, that answer could be challenged. I have the compact edition, and even that is two big, fat volumes (boxed, with a magnifying glass). The hard cover edition had 20 volumes, 21,728 pages. The OED is now being completely revised to produce an updated Third Edition.

What appealed to me was both the comprehensiveness of the listings and the inclusion of the history of each word.

The 19th century brought the creation of historical and etymological dictionaries, like the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) I discussed above, which began publication in 1884 and aimed to document the history and development of every English word!

Dictionary Types

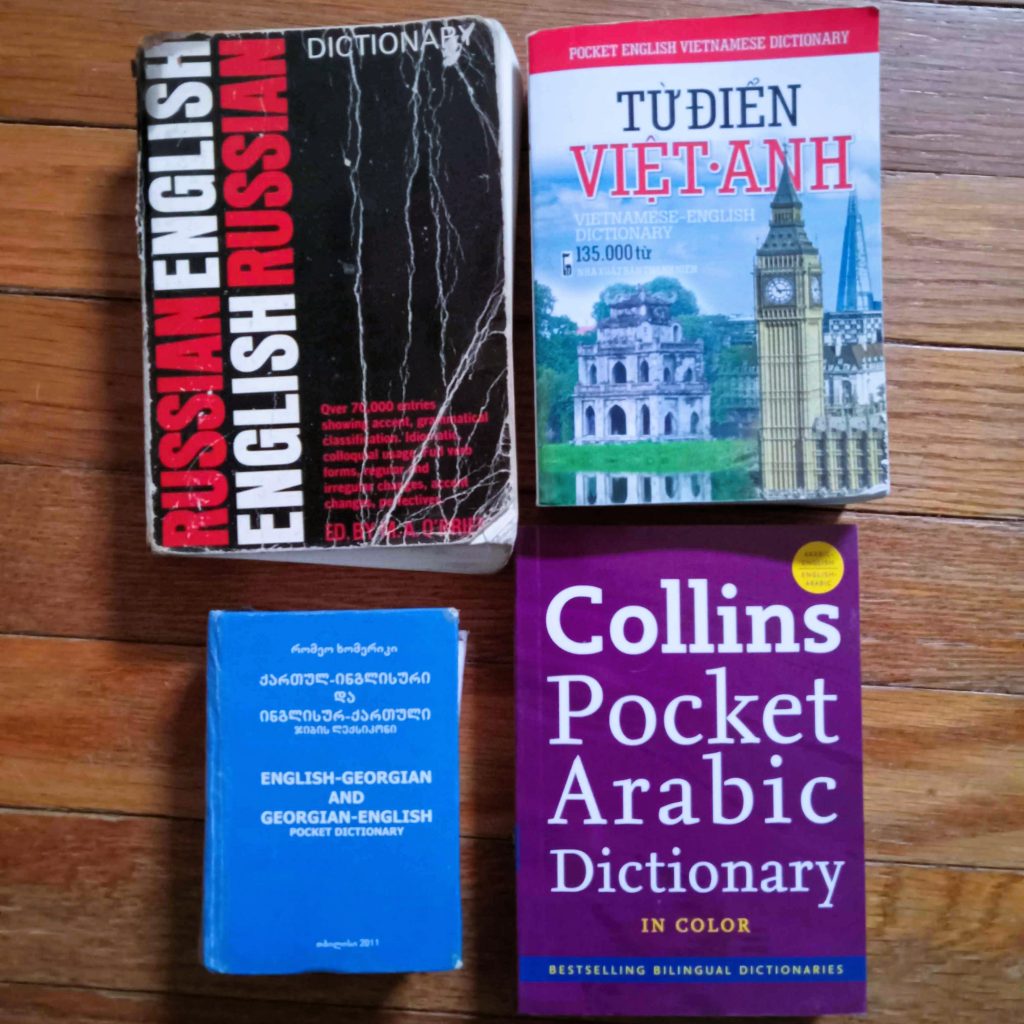

Dictionaries expanded to cover specialized fields, slang, and dialects. The 20th century saw the rise of bilingual dictionaries and learner’s dictionaries to support language education and globalization.

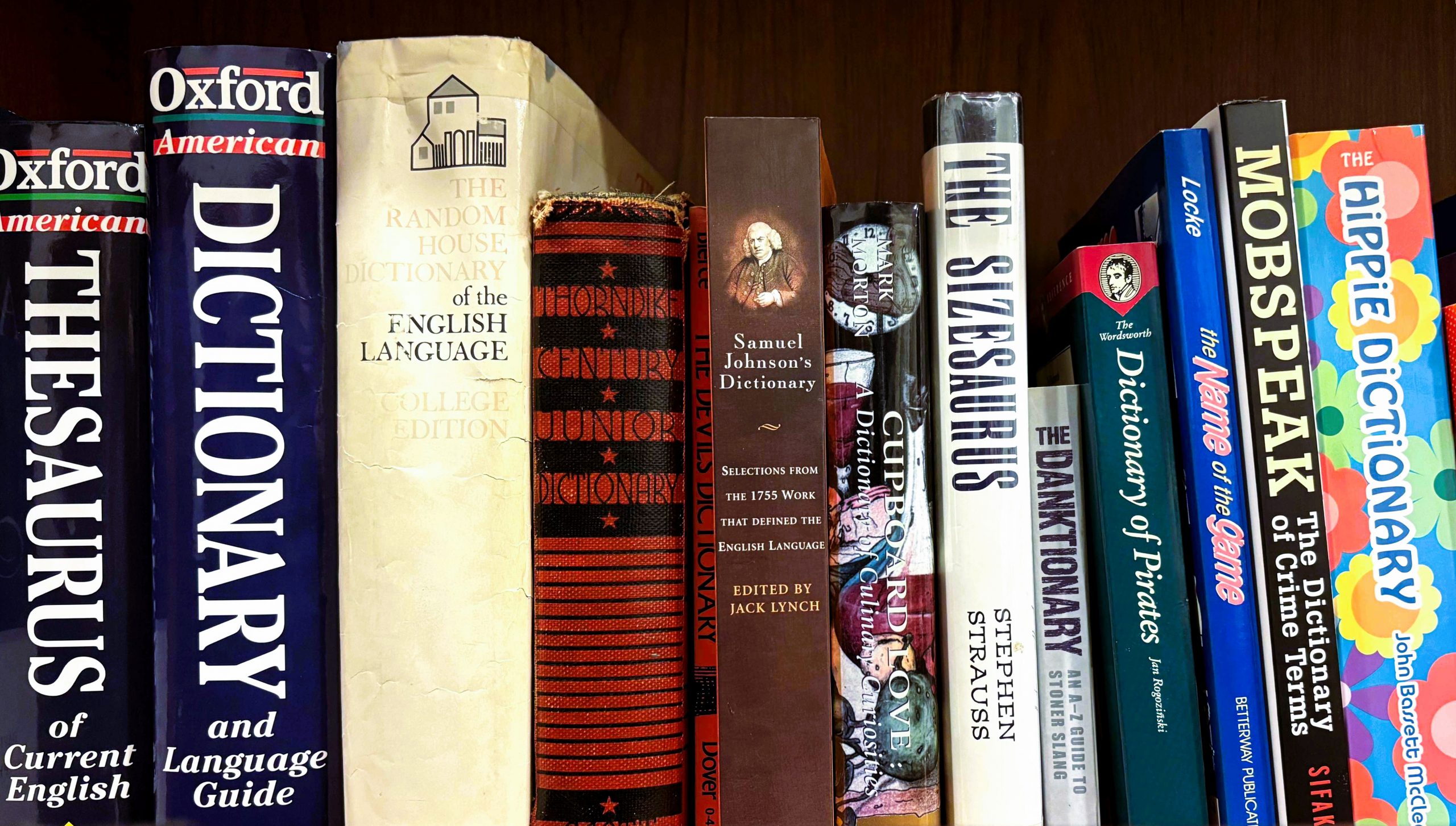

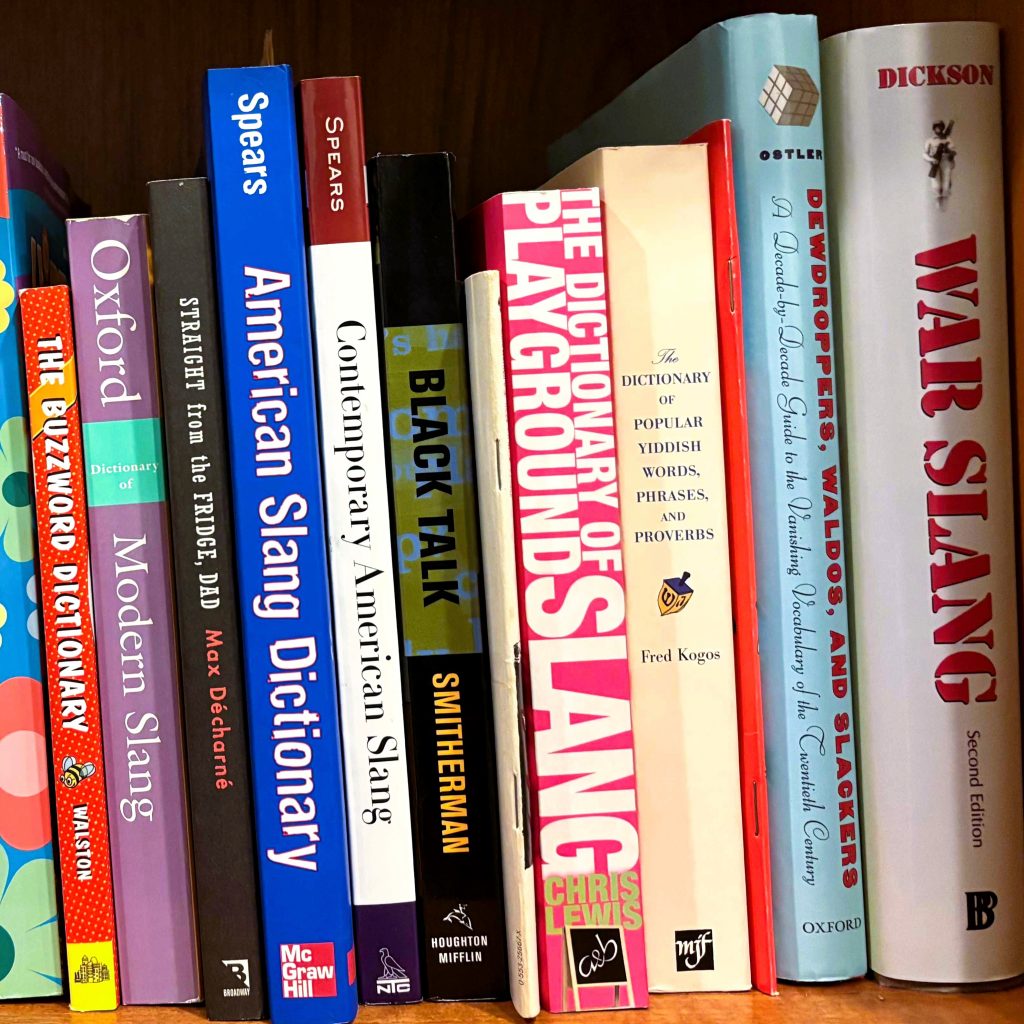

I started collecting dictionaries when I started writing fiction. I have shelf after shelf filled with them!

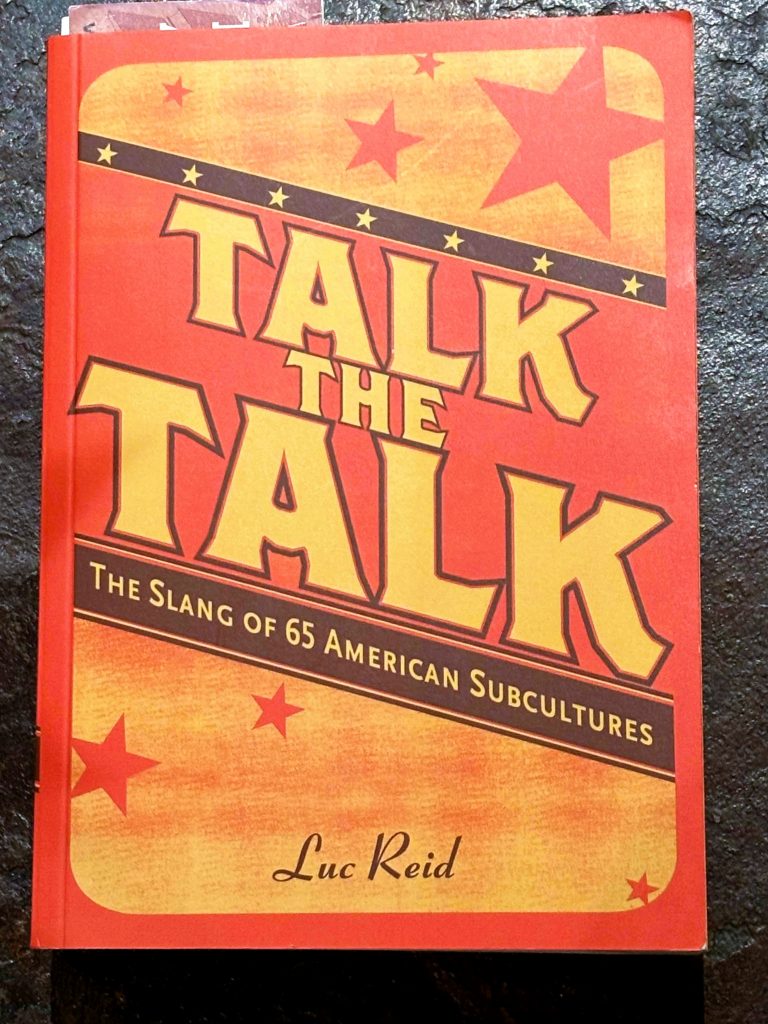

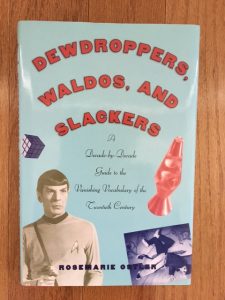

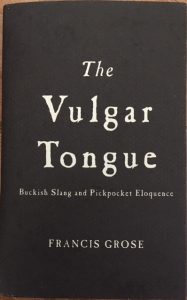

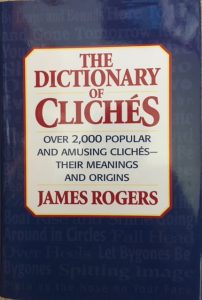

When one thinks of specialized dictionaries, medicine and law come immediately to mind. But for my purposes, I needed the common language.—i.e., slang. To seem authentic—real, if you will—the thoughts and dialogue of characters are crucial.

One of my favorite dictionaries is Talk the Talk: The Slang of 65 American Subcultures. Groups from stamp collectors to people living in Antarctica, from Birders to con artists, to Wiccans, witches, and neo-pagans are included. It’s a fun read even if you aren’t a writer!

The Dictionary in the Digital Age

The late 20th and early 21st centuries introduced electronic dictionaries and online databases, making dictionaries more accessible and interactive. Platforms like Merriam-Webster Online and the OED Online offer constantly updated entries and multimedia content.

Artificial intelligence and corpus linguistics have enabled dictionaries to be more descriptive and data-driven, reflecting real-world language use. But when looking for a word, a meaning, or a spelling online, that is what you will get: that one word. By contrast, according to the WSJ article cited above, “One of the pleasures of having a dictionary at hand is the serendipity of idle browsing—of progressing from ‘crankshaft’ to ‘cranky’ to ‘cranbog’…” Online, you don’t get more than you ask for.

Bottom Line: For some of us, online searches will never replace physical dictionaries in our hearts.