Tea has been entwined with human history for thousands of years. Humans being humans, that also means that tea has been integral to humans at war for as long as we’ve been drinking it.

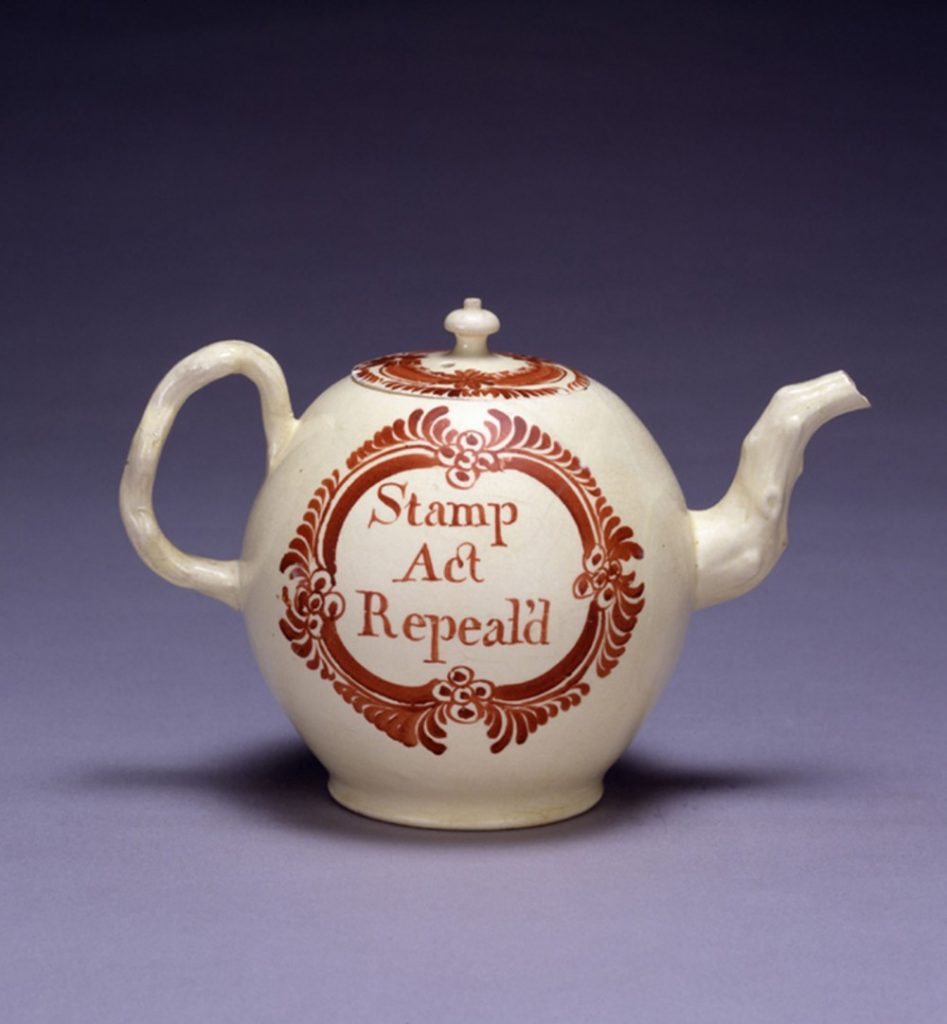

Tea in the Revolutionary War

As you may know from last week’s blog, tea played a pivotal role in U.S. history: the Tea Act of 1773 provoked the Boston Tea Party that escalated into the American Revolution. In fact, John Adams called tea a “Traitor’s Drink.” Boycotting traditional tea led to the creation of “Liberty Tea.”

Liberty Tea refers to a tea substitute created and drunk by colonists during the boycott. Patriotic Americans made these “teas” from native plants and herbs, such as raspberry leaf, cranberries, lemon and orange peel, chamomile, mint, rose petals, as well as other local botanicals such as blueberries, apples, strawberries, peppermint, and lavender—quite different from traditional black or green teas but cherished for their local origin, symbolism of resistance, and independence from British rule.

Tea in the American Civil War

After a 10-year total boycott of tea, it gradually regained its popularity in the States. By the middle of the 19th century, tea was back on American tables.

At the outbreak of the American Civil War, over half of America’s foreign–born population was British and Irish. In addition, although Britain was officially neutral, as many as 50,000 British and Irish men and women served in the two armies. Tea (or coffee) was a staple for soldiers on both sides, with gunpowder green tea being common among those who could get it. The availability of tea varied by side and era.

Tea for Votes!

“On July 9, 1848, five key members of the American women’s suffrage movement met for tea in Waterloo, New York: Lucretia Mott, Martha Wright, Mary Ann McClintock, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and hostess Jane Hunt. Over tea, these women expressed their views so passionately that while their meeting had probably started as a calm affair, it quickly became the launch pad for nothing less than the Seneca Falls Convention; this convention was the first women’s rights conference in the Western world, and it had started with a simple tea party.”

America’s Suffragette Movement Began with a Tea Party from Boston Tea Party Museum

Other suffragettes carried on this tradition, holding tea parties to raise funds and spread the message of the movement. In 1914, porcelain teapots, cups, and saucers inscribed with Votes for Women appeared at fundraising events. Women were granted the right to vote in the U.S. in 1920, so one might say that era started another American revolution.

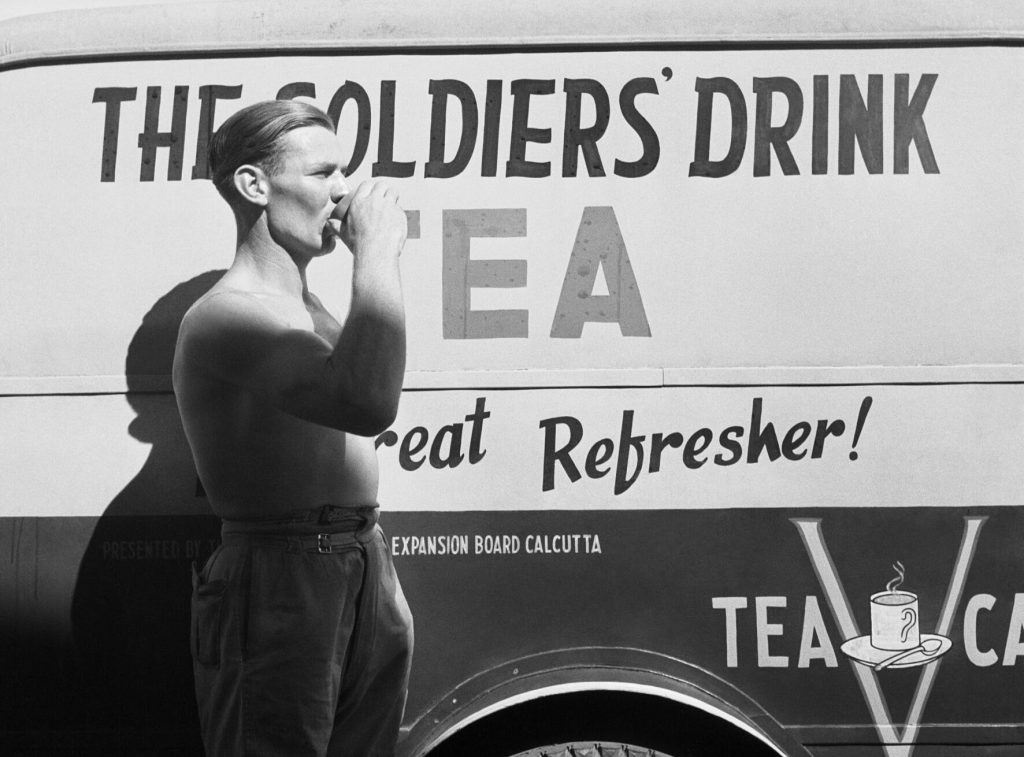

Tea in the British Army

Tea became a staple in the British military from the 18th century onward, and commanders often issued tea to soldiers during campaigns, especially in colonial regions like India. The British army’s inability to ensure regular tea supplies to soldiers in the Crimean War spurred efforts to improve military logistics. It was—and is—valued for its caffeine content, which helped soldiers stay alert, and its value as a comforting ritual in harsh conditions is often mentioned.

Tea in World War I

As mentioned in last week’s blog, tea bags remarkably similar to the modern ones were patented in 1901. During World War I, tea was an important beverage, especially for troops from Britain and other parts of the British Empire. Tea was included in the soldiers’ rations, typically in the form of tea leaves or bagged tea. Soldiers would brew tea using water heated over small stoves or fires in the trenches. Tea helped keep soldiers warm and hydrated in cold, damp trenches. It served not only as a comforting beverage but also as a morale booster amid the horrors of that war.

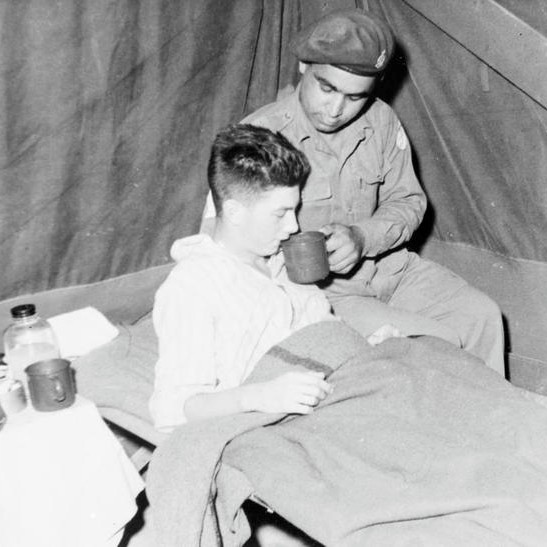

Tea in World War II

“Instant tea” (similar to freeze-dried instant coffee) was developed in the 1930s. During World War II, British and Canadian military command issued instant tea in soldiers’ ration packs.

In 1942, the British government bought all the black tea available on the European market to ensure their soldiers had a steady supply on the front lines. In the field, soldiers improvised a variety of heating elements to boil water for tea, including igniting sand mixed with petrol and taking advantage of heat coming off vehicle engines.

Tea at War Around the World

But focusing on Britain gives a very unbalanced view of when and where tea went to war!

Chinese Armies

People in China have been consuming tea for thousands of years. Ancient Chinese armies relied on tea for its stimulant properties and as a way to stay hydrated during long campaigns.

Soldiers likely drank it both for health and morale.

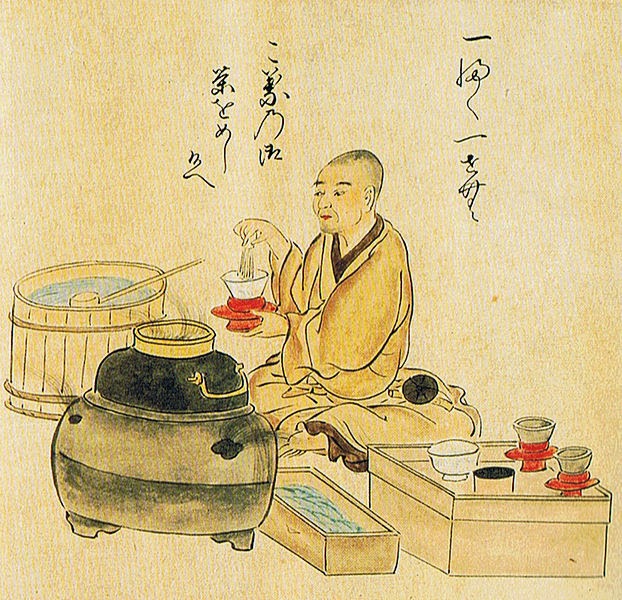

Japanese Samurai and Military

Samurai warriors incorporated tea ceremonies into their culture, emphasizing mindfulness and discipline. In fact, samurai were the first to practice the original tea ceremony, Ueda Sōko Ryū (上田宗箇流). While not a battlefield staple, tea was part of the broader warrior ethos.

Later Japanese military forces also consumed tea, valuing its practical benefits.

Russian Army

According to legend, Cossack military leaders visited China in 1567, where they encountered tea and brought it back to Russia. Tea became popular in Russia from the 17th century and was widely consumed by soldiers as a warming drink, especially important in cold climates.

Tea helped maintain morale and provided warmth during harsh Russian winters.

Indian Armies

In India, the military under the British Raj largely created the domestic market for tea. Though the British East India Company established tea plantations in India in the 1820s, the majority of the tea produced was a cash crop destined for export. The Indian Tea Cess bill of 1903 was an attempt to promote domestic tea consumption in India by means of an export tax on locally grown tea, though this was only marginally successful.

However, the tea-drinking habits of working-class British soldiers stationed in India spread to Indian members of the army. Like their British counterparts, Indian soldiers (sepoys) developed a taste for the sweet, milky tea that made up a significant portion of their daily calories. In the 1860s, military commanders experimented with communally-available kettles of tea constantly boiling in army camps in Pune.

Tea sellers set up stalls at train stations along Indian railroads, further spreading the popularity of tea among military and civilian train passengers.

Mongol Armies

Mongol warriors drank a form of tea made from fermented milk, salt, millet, and tea leaves (similar to Tibetan butter tea) to sustain energy during long campaigns across harsh terrains. A Mongolian soldier required approximately 3,600 calories every day just to stave off malnutrition while on campaign. Süütei tsai (ᠰᠦ᠋ ᠲᠡᠢᠴᠠᠢ) provided a significant portion of the daily caloric needs of a soldier.

In short, tea has been a common drink among armies in Britain, China, Japan, Russia, India, and Mongolia, among others. Its stimulating caffeine, warming properties, and cultural significance made it a valuable commodity for those facing the hardships of military life.

Tea and the Opium War

Apart from militaries’ reliance on tea for consumption, tea has played a major role in world politics and economics. A prime example is the role of tea in the Opium Wars, intertwining commerce, colonialism, and cultural exchange with profound consequences.

In the 18th and early 19th centuries, tea was such a prized commodity in Britain and Europe, that Britain had a massive trade imbalance with China: they imported vast quantities of tea, silk, and porcelain but had little that the Chinese wanted in return.

To correct this imbalance, British traders began exporting opium grown in British-controlled India to China. Opium sales exploded, creating widespread addiction and social problems. The Chinese government attempted to suppress the opium trade, leading to tensions with Britain.

The conflicts arose primarily because of British insistence on free trade, including the opium trade, and Chinese efforts to enforce their laws banning opium.

Tea was indirectly central to these wars as the demand for tea was a key driver of the British desire to continue trading with China on their terms, including the opium trade.

After the War

The wars resulted in China’s defeat, leading to the Treaty of Nanking (1842) and other unequal treaties, which opened several Chinese ports to British trade; ceded Hong Kong to Britain; and allowed British merchants greater freedom to trade, including tea. The Opium Wars marked the beginning of the “Century of Humiliation” for China, affecting its sovereignty and economy for decades.

The forced opening of China contributed to the expansion of the global tea trade. Tea became a symbol of British imperialism but also a cultural bridge, becoming deeply embedded in British identity.

Tea is more than just a beloved beverage. It’s been a catalyst in the complex economic and political dynamics that have sparked conflict, and reshaped global trade and colonial relations.

A related example is covered in a book by Andrew B. Liu. As the subtitle indicates, Tea War: A History of Capitalism in China and India isn’t about a literal war. However, it underscores yet again the importance of tea in world affairs.

Bottom Line: Tea is a centuries-old octopus, with tentacles reaching into virtually all aspects of human history.