Back in December 2022, my sister-in-law and brother asked if I’d like to go with them and their friend to Vietnam. After figuring out financing for airfare and updating my passport, the most important concern for me was speaking Vietnamese.

I’ve studied several other languages in my life, but speaking Vietnamese was particularly difficult for me. The US State Department Foreign Language Institute classifies Vietnamese as a “Category III” language, the second most difficult language for English-speakers to learn. They estimate it would take someone approximately 1,100 class hours to reach a working proficiency in Vietnamese. I think they were being optimistic.

Singing Vietnamese

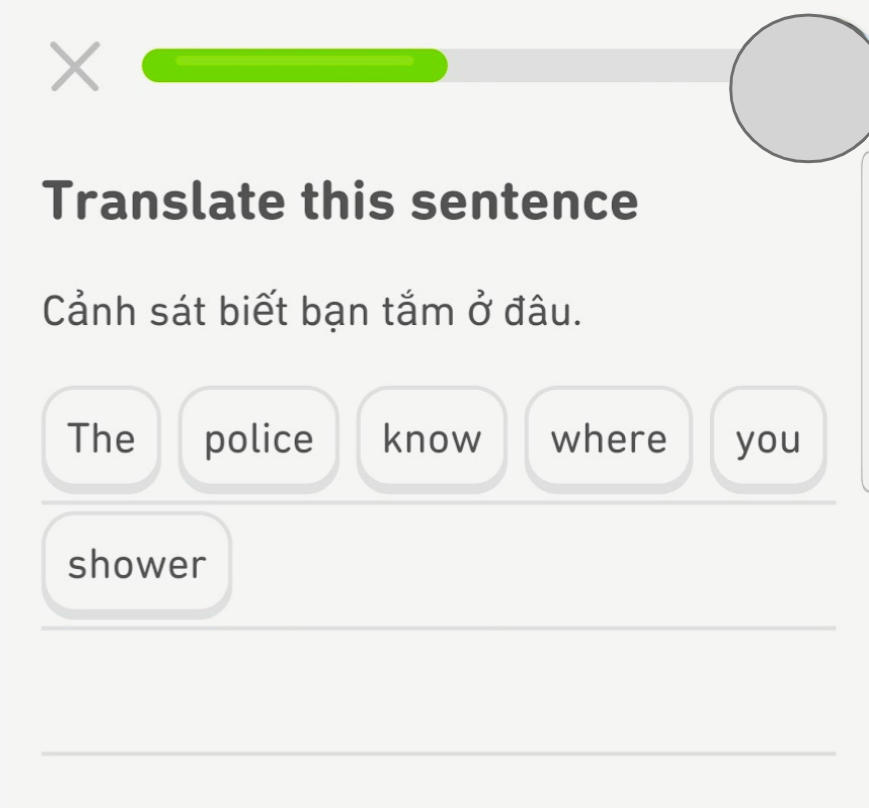

In addition to availing myself of a textbook, a language learning program on my phone, multiple audiobooks and podcasts, and all the questions I could pester my sister-in-law with, I took Vietnamese classes at the local Buddhist temple. Our teacher made us practice singing phrases to each other to wrap our heads around the idea of tones in daily speech.

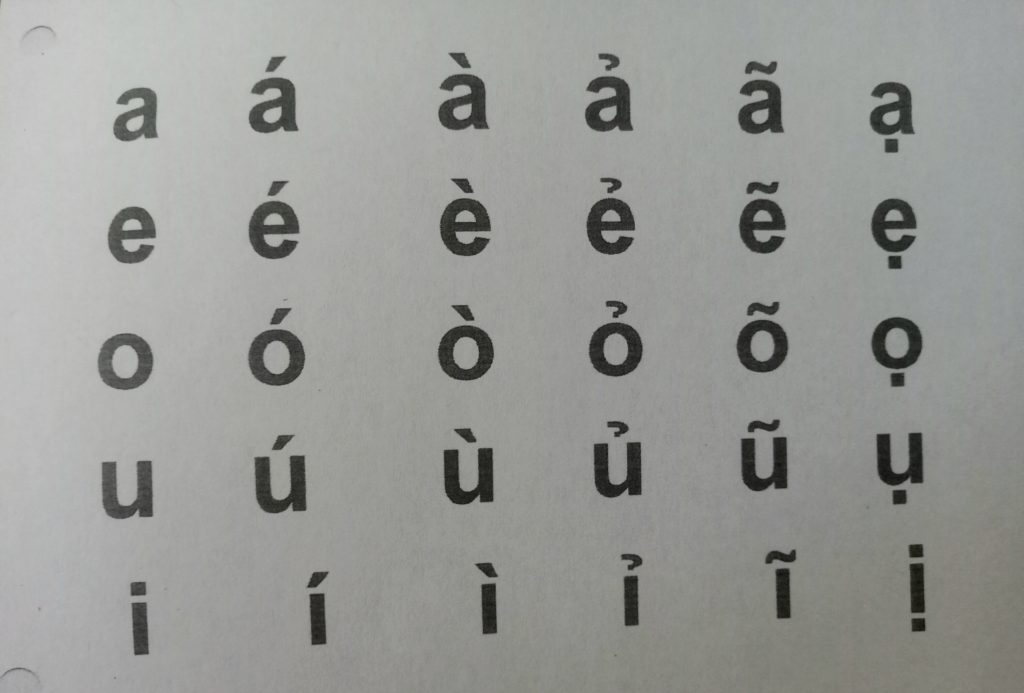

I still tend to move my hands or my chin up and down when I’m trying to make my voice distinguish between a sắc (upwards) and huyền (downwards) tone. As you can imagine, I look a bit silly when speaking Vietnamese. However, I sound even sillier when I don’t pronounce the tones correctly.

Essentially, I’m saying, “Gwide meernong!” instead of “Good morning!” when I use the wrong tones. And then I wonder why people can’t understand me…

Speaking Child(ese)

My sister-in-law and her friend caught up with friends and family they haven’t seen in years. We spent a lot of time with children of those friends and family members, and those children often spoke only a little English.

I quickly learned a lot of Vietnamese for specific situations that never arose in my textbooks or language apps. “Hold my hand!” “Do you need to go potty?” “What a pretty dolly!”

I also, for reasons I could never quite figure out, stood out as a foreigner every place I went. It must have been my shoes. My obvious alien-ness seemed to translate into being American somehow. (A Danish woman I met at a hotel told me everyone also assumed she was American.) Any time I went out in public, children would run up to me to say, “Hello! What is your name? Good morning! How are you? I am fine, thank you!” and then run off, giggling madly.

A similar thing happened when I worked as an English teacher in another country. I’ve gotten pretty good at holding conversations in very slow, carefully enunciated English, following the dialogue patterns that show up most often in beginner English textbooks. And then I learned how to respond in multiple languages to the proud parents inevitably standing nearby. “Your child is very smart/ handsome/ clever/ good!”

Animal(ese)

When I went through the lesson on animals on the language learning program, I thought, “Why am I bothering with this? When are ducks and dragons ever going to come up in conversation?” I turned out to be quite wrong.

For some reason, those words stuck in my brain more than any others. Any time I saw an animal, the Vietnamese word flashed up in my brain and popped out of my mouth. Cat! Cow! Chicken!

The kids always found this highly amusing. The adults around me thought I was maybe a bit strange.

This came in quite handy when trying to order food. The words for living animals and types of meat are the same in Vietnamese, differentiated by a classifier. Con heo (pig) becomes thịt heo (pork). I was reading Vietnamese, even if I wasn’t quite speaking Vietnamese.

The Most Important Vietnamese

Very often, I tried speaking Vietnamese to order food and then had no idea what I was eating. I never had anything less than delicious, but I often couldn’t quite identify it.

I learned key phrases to look out for, like “spicy” and “alcohol.” I never wound up in tears from fiery pepper sauce or accidentally drunk on something I hadn’t realized was alcoholic. I did find myself eating lots of combinations I wouldn’t have thought of and things I’d never have considered putting on a plate. Morning glories, sauteed with garlic, make a delicious addition to salad. Jackfruit, smothered in peanut sauce, tastes like chicken!

One time, I accidentally swapped the vowels in coconut and found myself drinking strawberry tea. I’m still not sure what I asked for when I received a bowl of flan, peanuts, and coffee.

Technology(ese)

The last time I found myself immersed in a new language, I had very limited internet access and relied on pocket dictionaries to bridge the gap when my vocabulary fell short. I admit to being something of a Luddite still, and one of the first things I bought in Vietnam was a dual-language dictionary. However, people around me happily embraced the new tools available. Results varied.

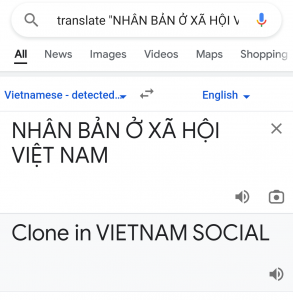

My brother could take a picture of a menu or a shop sign in Vietnamese and read an English translation on his phone screen. According to his phone, the menu then offered him “delightful hot” and “pig bubbles.”

In Huế, a friend’s family offered to show us how to harvest peanuts! No one in the group who took us to the peanut field spoke English, so we did our best to follow the pantomime. (All I could do was to repeatedly point out the water buffalo in the next field.) Suddenly, we heard British woman’s voice behind us, telling us to “Follow the farmer’s instructions.” One of the cousins had opened a translation app on his phone and used it to speak to us.

Different Dialect(ese)

People in Vietnam speak a wide range of dialects and even entirely different languages. Most translation software, language learning programs, and textbooks focus on the northern dialect, spoken in Hanoi. When people in southern Vietnam tried to use my brother’s spoken translation app, the program spit out gibberish.

Huế sits about mid-way between the northern and southern borders of Vietnam. The dialect people speak there sounds quite different to the dialect people speak in Sóc Trăng, where my sister-in-law’s family lives. In Huế, my sister-in-law could only understand people speaking Vietnamese if they spoke slowly and enunciated.

The vocabulary, word usage, pronunciation, and even the vocal tones varied so widely from place to place that I found myself relying on written Vietnamese, which is the same in every region. In Sóc Trăng, way down south, I could almost understand people when they spoke. In Hội An and Da Nang, further north, people could almost understand me when I spoke.

My Future in Vietnam(ese)

I’ve decided (my husband doesn’t know this yet) that I’m going to retire to Vietnam at some point in the future. I’ll rent a house, offer English lessons, and eat all the mangoes and coconuts I can get my hands on.

Before I do that, I’ll have to up my skills quite a bit. According to a 2022 study by the Stockholm School of Economics, Vietnamese students outperform students in countries like Britain and Canada. Vietnamese teachers are among the best in the world, and they receive frequent training and support from the government and the Education Ministry.

For now, I’m going back to the temple for more Vietnamese lessons. Maybe I’ll be speaking Vietnamese properly by the time I turn 80!