Today’s blog entry was written by Kathleen Corcoran, a local harpist, writer, editor, favorite auntie, turtle lover, canine servant, and English as a Foreign Language (EFL) teacher.

Believe it or not, not everyone speaks English as a native language. To strain credulity further, consider that not every character learned English as a native language. Shocking, I know!

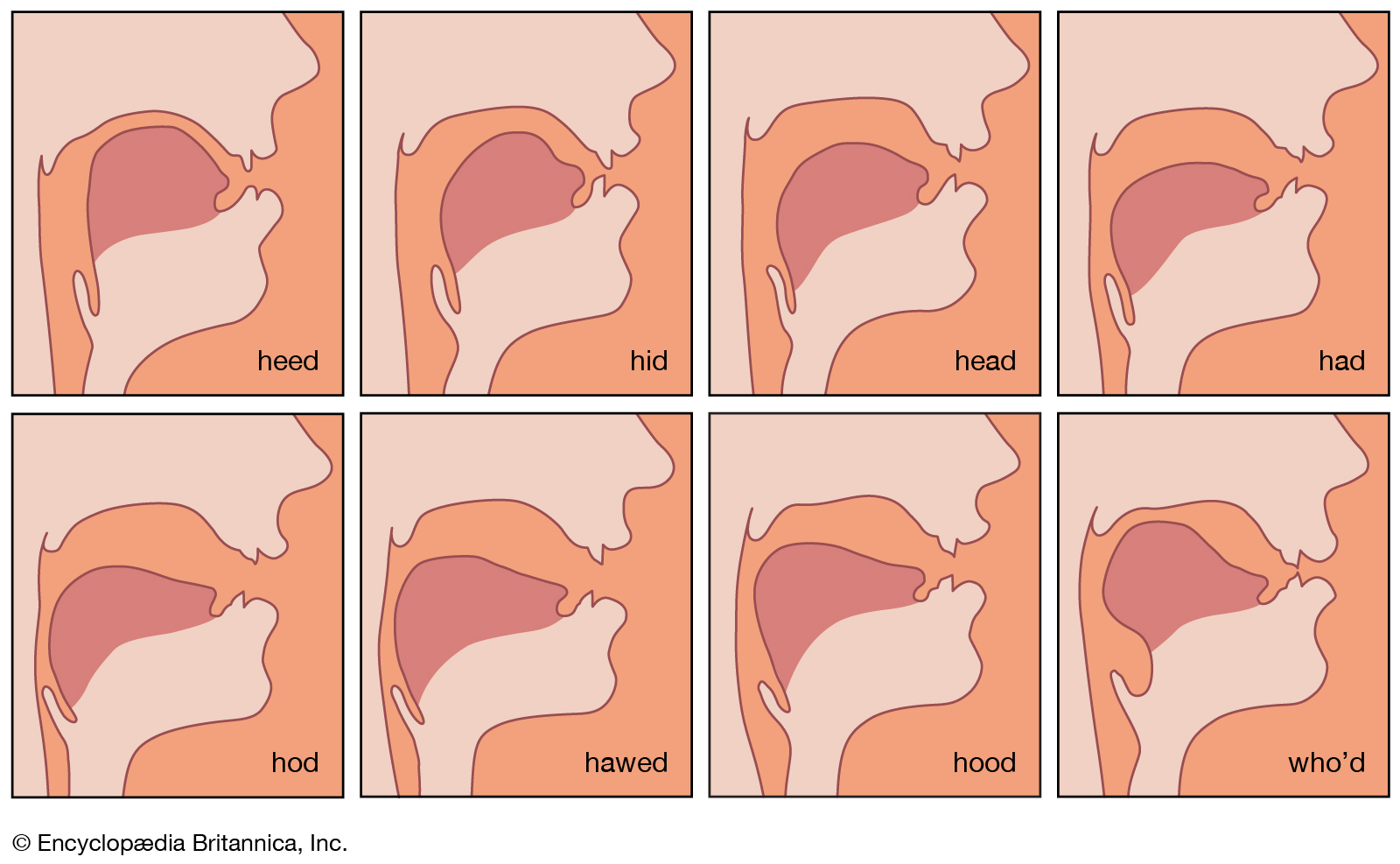

But how to convey through written words that a speaker has an accent?

One method is to transcribe phonetically the way a character speaks, as the late, great Sir Terry Pratchett demonstrated so well. A vampire in his fantasy universe of Discworld, deliberately emphasizes his accent when he wants to appear odd rather than threatening.

“Vell, I’m not official,” said Otto. “I do not haf zer sword and zer badge. I do not threaten. I am just a vorking stiff. And I make zem laff.”

from Thud! by Terry Pratchett

But what about a subtler signifier of a character’s foreign origins? There could be a million reasons to let your audience know that a character was originally not a member of the “in” group.

- Signal that a character will have a different cultural perspective when reacting to events.

- Sign that a character, by virtue of a different upbringing, has insight or expertise others may need.

- Foreshadowing of any kind of discrimination practiced against a group designated as “others.”

- Mockery of any slight difference shows the character of the people mocking as well as those standing by and those reacting.

- Very subtle differences can clue in a reader that something is off, for example a spy or an imposter.

Fortunately for our purposes as writers, English is weird. So many rules have exceptions or no reasonable guidelines of when to apply them…. it’s enough to drive any ESL student mad. If any of these rules (that you probably follow without noticing) are broken, that’s enough to make a reader notice that something is off.

Articles

Should a noun have a definite or indefinite article? Or no article at all? Go ahead and try to explain the rules without looking it up. I’ve been an EFL teacher for years (and occasionally an ESL teacher), and I still mix things up. Like most native English speakers, I tend to rely on what sounds right.

If your non-native English speaker hails from a real country on Earth (as opposed to another planet or a fantasy realm), you can simply have the character follow the rules of their native language. A native French speaker would be likely to overuse articles. A native Russian speaker might skip articles altogether.

Consider these examples:

- Quick brown fox jumping over lazy dog.

- The dog, she is lazy. A fox jumps over the dog, no problem.

Of course, if the character learned a language you’ve made up, the rules are entirely up to you.

Word Order

English, like Bulgarian and Swahili, is a SVO language; Subject Verb Object is the typical sentence structure. The meaning of a sentence can be changed simply by changing the word order. The most common word order is SOV– the verb comes at the end of the sentence, after the object. Qartuli and Mongolian are SOV languages.

Other common sentence structures include VSO (Hawaiian), VOS (Malagasy), OVS (Hixkaryana), and OSV (Xavante). Trying to fit English sentences into any of these other structures can create some very awkward conversations.

Just to be contrary, Latin word order makes no difference to the meaning of a sentence and is often jumbled deliberately for poetic effect. (I’m looking at you, Virgil!)

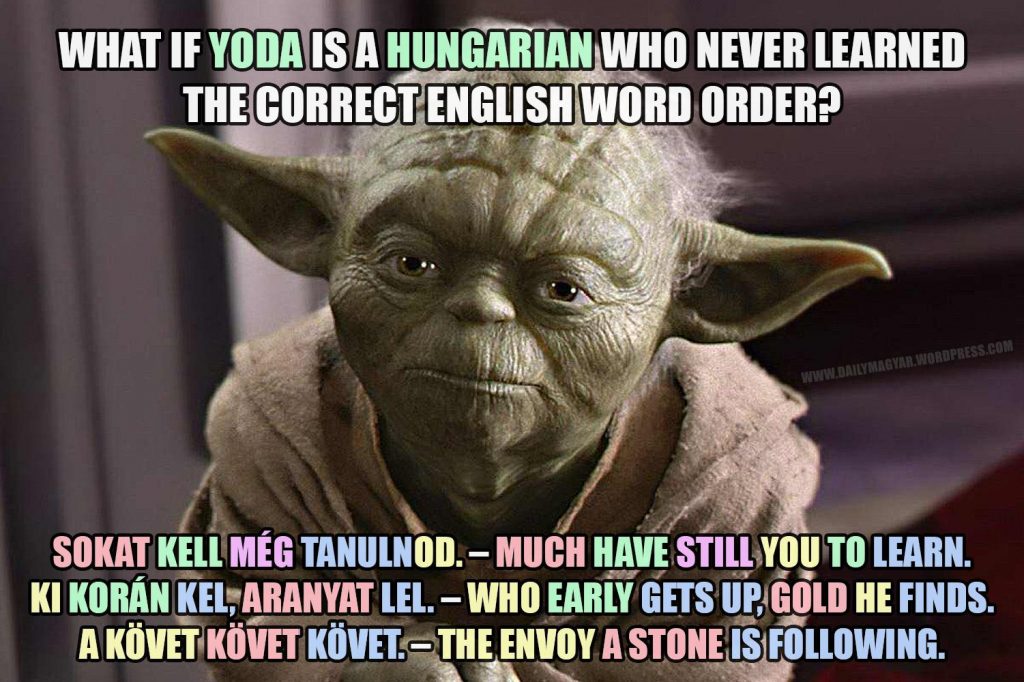

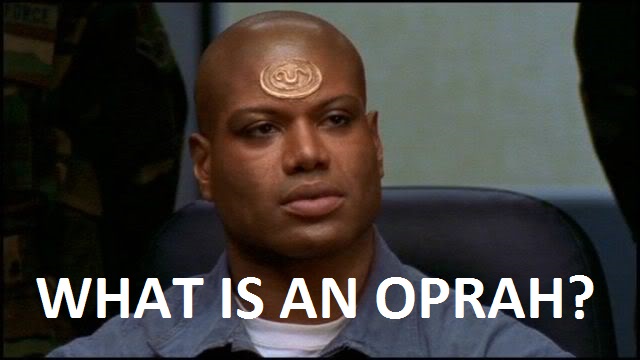

Yoda is one of the most widely known characters who speaks English with inverted word order. Although he has no obvious accent, his speech immediately lets the audience know that he is alien.

Agreement

Some languages have declensions and conjugations and all sorts of ways in which words change form to indicate specifics. Others have separate words to indicate number, tense, intention, etc., though the word itself stays the same. English has both.

Sometimes verbs change when they’re in the past tense (walk-walked); sometimes they don’t (put-put). Just for fun, some verbs change into entirely different words when they change tense (bear-bore).

Nouns are just as bizarre. In kindergarten, the teacher told me I just had to put an S at the end of the word. Then there were geese, children, moose, alumni, crises, and vortices. I still haven’t figured out the rule for the cello.

Naturally, this is an area of difficulty for many people who did not learn English as children. It’s also an area of difficulty for people who have been speaking English since infancy.

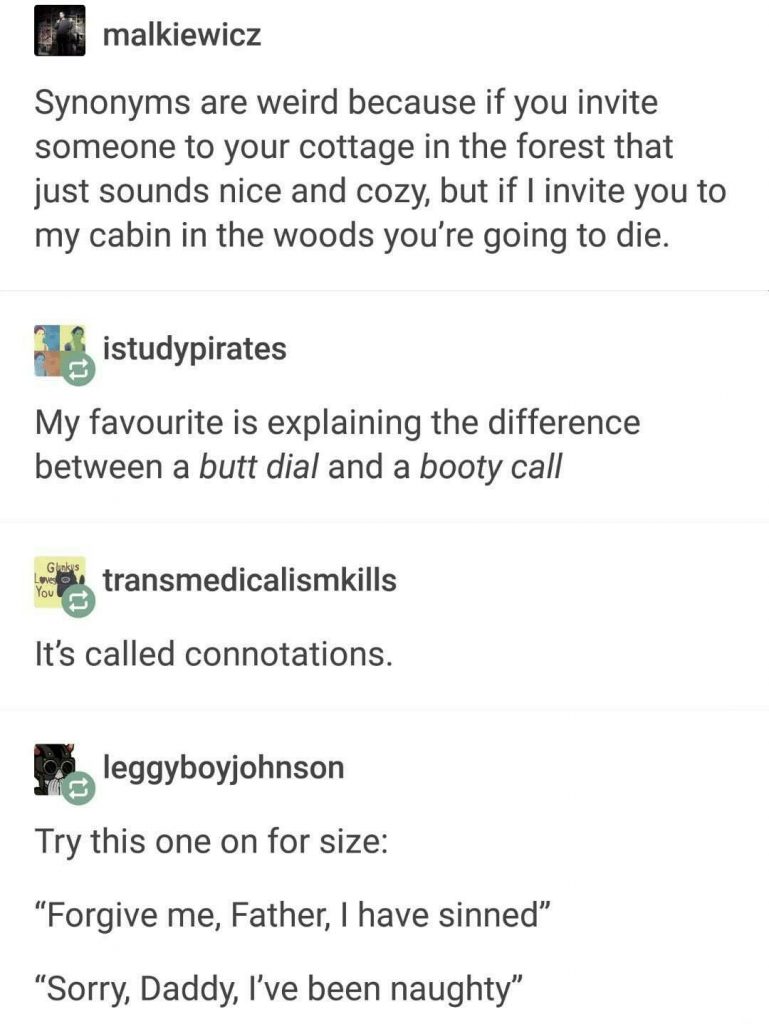

Idioms and Connotations

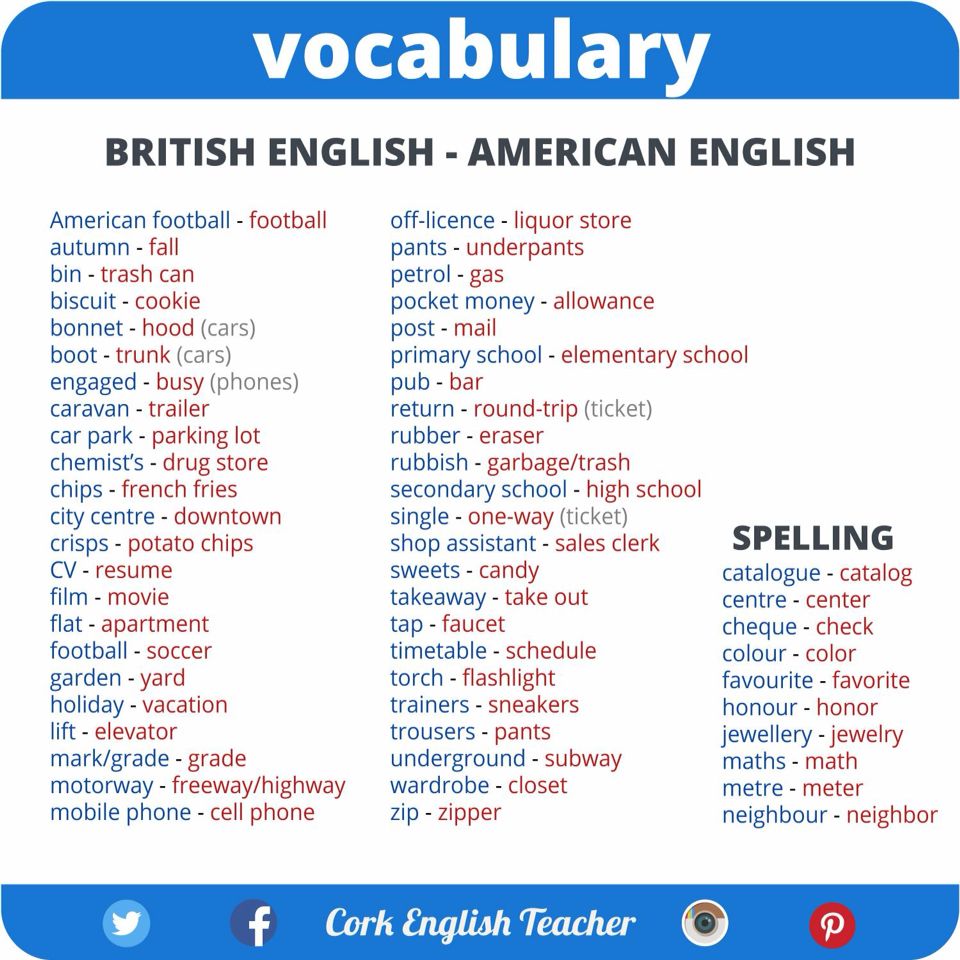

Even if a character speaks English absolutely fluently, there are still a million linguistic tripwires. A native English speaker from Minnesota will still have trouble understanding casual speech in Scotland.

I once watched a Scottish man and a South African man argue about something (I think it was Australian immigration policy, but that’s just a guess). They were mutually unintelligible. As they grew more excited, each slipped further into his native accent and became less understandable by the other. Theoretically, all three of us spoke the same language. In practice, I felt like I was watching a verbal tennis match that gradually turned into frantic hand gestures and facial expressions. It was both surreal and hilarious!

Other Sources

Translators are very useful sources for learning the grammar of a language you don’t know. If you want to have a character be newly arrived in Australia from Siberia, try looking at the translator’s notes in a new edition of War and Peace.

- Mobi Warren, a translator of Hermitage Among the Clouds by Thích Nhất Hạnh, explained some of the difficulties in translating Vietnamese into English. He wrote, “All this moving between past and present is more easily expressed in Vietnamese, a language in which none of the words have tenses.”

- Ancient writers can be particularly difficult to translate to modern English, but understanding those difficulties is a great way to highlight changes over time. If you’re trying to invent a language for a fantasy or science fiction setting, try basing the grammar on ancient Egyptian or Shang dynasty Chinese.

Another very useful source for finding ways to indicate non-native English speakers in dialogue is to look at resources for teaching English as a Second Language or English as a Foreign Language. If other teachers point out an area that’s particularly difficult, odds are that a character you write would have trouble with that same area.

Bottom Line: Lack of fluency is not the same as lack of intelligence. Odd speech patterns imply accents without needing to use odd spelling.

To a true New Yorker, this short story is not in an accent but is one of the few stories which is not in any accent.

ONLY THE DEAD KNOW BROOKLYN

By Thomas Wolfe 1935

Dere’s no guy livin’ dat knows Brooklyn t’roo an’ t’roo, because it’d take a guy a lifetime just to find his way aroun’ duh goddam town.

So like I say, I’m waitin’ for my train t’ come when I sees dis big guy standin’ deh—dis is duh foist I eveh see of him. Well, he’s lookin’ wild, y’know, an’ I can see dat he’s had plenty, but still he’s holdin’ it; he talks good an’ is walkin’ straight enough. So den, dis big guy steps up to a little guy dat’s standin’ deh, an’ says, “How d’yuh get t’ Eighteent’ Avenoo an’ Sixty-sevent’ Street?” he says.

“Jesus! Yuh got me, chief,” duh little guy says to him. “I ain’t been heah long myself. Where is duh place?” he says. “Out in duh Flatbush section somewhere?”

“Nah,” duh big guy says. “It’s out in Bensenhoist. But I was neveh deh befoeh. How d’yuh get deh?”

“Jesus,” duh little guy says, scratchin’ his head, y’know—yuh could see duh little guy didn’t know his way about—“yuh got me, chief. I neveh hoid of it. Do any of youse guys know where it is?” he says to me.

“Sure,” I says. “It’s out in Bensenhoist. Yuh take duh Fourt’ Avenoo express, get off at Fifty-nint’ Street, change to a Sea Beach local deh, get off at Eighteent’ Avenoo an’ Sixty-toid, an’ den walk down foeh blocks. Dat’s all yuh got to do,” I says.

“G’wan!” some wise guy dat I neveh seen befoeh pipes up. “Whatcha talkin’ about?” he says—oh, he was wise, y’know. “Duh guy is crazy! I tell yuh what yuh do,” he says to duh big guy. “Yuh change to duh West End line at Toity-sixt’,” he tells him. “Get off at Noo Utrecht an’ Sixteent’ Avenoo,” he says. “Walk two blocks oveh, foeh blocks up,” he says, “an’ you’ll be right deh.” Oh, a wise guy, y’know.

“Oh, yeah?” I says. “Who told you so much?” He got me sore because he was so wise about it. “How long you been livin’ heah?” I says.

“All my life,” he says. “I was bawn in Williamsboig,” he says. “An’ I can tell you t’ings about dis town you neveh hoid of,” he says.

“Yeah?” I says.

“Yeah,” he says.

“Well, den, you can tell me t’ings about dis town dat nobody else has eveh hoid of, either. Maybe you make it all up yoehself at night,” I says, “befoeh you go to sleep—like cuttin’ out papeh dolls, or somp’n.”

“Oh, yeah?” he says. “You’re pretty wise, ain’t yuh?”

“Oh, I don’t know,” I says. “Duh boids ain’t usin’ my head for Lincoln’s statue yet,” I says. “But I’m wise enough to know a phony when I see one.”

“Yeah?” he says. “A wise guy, huh? Well, you’re so wise dat someone’s goin’ t’bust yuh one right on duh snoot some day,” he says. “Dat’s how wise you are.”

Well, my train was comin’, or I’da smacked him den and dere, but when I seen duh train was comin’, all I said was, “All right, mugg! I’m sorry I can’t stay to take keh of you, but I’ll be seein’ yuh sometime, I hope, out in duh cemetery.” So den I says to duh big guy, who’d been standin’ deh all duh time, “You come wit me,” I says. So when we gets onto duh train I says to him, “Where yuh goin’ out in Bensenhoist?” I says. “What numbeh are yuh lookin’ for?” I says. You know—I t’ought if he told me duh address I might be able to help him out.

“Oh,” he says, “I’m not lookin’ for no one. I don’t know no one out deh.”

“Then whatcha goin’ out deh for?” I says.

“Oh,” duh guy says, “I’m just goin’ out to see duh place,” he says. “I like duh sound of duh name”—Bensenhoist, y’know—“so I t’ought I’d go out an’ have a look at it.”

“Whatcha tryin’ t’hand me?” I says. “Whatcha tryin’ t’do—kid me?” You know, I t’ought duh guy was bein’ wise wit me.

“No,” he says, “I’m tellin’ yuh duh troot. I like to go out an’ take a look at places wit nice names like dat. I like to go out an’ look at all kinds of places,” he says.

“How’d yuh know deh was such a place,” I says, “if you neveh been deh befoeh?”

“Oh,” he says, “I got a map.”

“A map?” I says.

“Sure,” he says, “I got a map dat tells me about all dese places. I take it wit me every time I come out heah,” he says.

And Jesus! Wit dat, he pulls it out of his pocket, an’ so help me, but he’s got it—he’s tellin’ duh troot—a big map of duh whole goddam place wit all duh different pahts. Mahked out, you know—Canarsie an’ East Noo Yawk an’ Flatbush, Bensenhoist, Sout’ Brooklyn, duh Heights, Bay Ridge, Greenpernt—duh whole goddam layout, he’s got it right deh on duh map.

“You been to any of dose places?” I says.

“Sure,” he says, “I been to most of ’em. I was down in Red Hook just last night,” he says.

“Jesus! Red Hook!” I says. “What-cha do down deh?”

“Oh,” he says, “nuttin’ much. I just walked aroun’. I went into a coupla places an’ had a drink,” he says, “but most of the time I just walked aroun’.”

“Just walked aroun’?” I says.

“Sure,” he says, “just lookin’ at things, y’know.”

“Where’d yuh go?” I asts him.

“Oh,” he says, “I don’t know duh name of duh place, but I could find it on my map,” he says. “One time I was walkin’ across some big fields where deh ain’t no houses,” he says, “but I could see ships oveh deh all lighted up. Dey was loadin’. So I walks across duh fields,” he says, “to where duh ships are.”

“Sure,” I says, “I know where you was. You was down to duh Erie Basin.”

“Yeah,” he says, “I guess dat was it. Dey had some of dose big elevators an’ cranes an’ dey was loadin’ ships, an’ I could see some ships in drydock all lighted up, so I walks across duh fields to where dey are,” he says.

“Den what did yuh do?” I says.

“Oh,” he says, “nuttin’ much. I came on back across duh fields after a while an’ went into a coupla places an’ had a drink.”

“Didn’t nuttin’ happen while yuh was in dere?” I says.

“No,” he says. “Nuttin’ much. A coupla guys was drunk in one of duh places an’ started a fight, but dey bounced ’em out,” he says, “an’ den one of duh guys stahted to come back again, but duh bartender gets his baseball bat out from under duh counteh, so duh guy goes on.”

“Jesus!” I said. “Red Hook!”

“Sure,” he says. “Dat’s where it was, all right.”

“Well, you keep outa deh,” I says. “You stay away from deh.”

“Why?” he says. “What’s wrong wit it?”

“Oh,” I says, “it’s a good place to stay away from, dat’s all. It’s a good place to keep out of.”

“Why?” he says. “Why is it?” Jesus! Whatcha gonna do wit a guy as dumb as dat? I saw it wasn’t no use to try to tell him nuttin’, he wouldn’t know what I was talkin’ about, so I just says to him, “Oh, nuttin’. Yuh might get lost down deh, dat’s all.”

“Lost?” he says. “No, I wouldn’t get lost. I got a map,” he says.

A map! Red Hook! Jesus!

So den duh guy begins to ast me all kinds of nutty questions: how big was Brooklyn an’ could I find my way aroun’ in it, an’ how long would it take a guy to know duh place.

“Listen!” I says. “You get dat idea outa yoeh head right now,” I says. “You ain’t neveh gonna get to know Brooklyn,” I says. “Not in a hunderd yeahs. I been livin’ heah all my life,” I says, “an’ I don’t even know all deh is to know about it, so how do you expect to know duh town,” I says, “when you don’t even live heah?”

“Yes,” he says, “but I got a map to help me find my way about.”

“Map or no map,” I says, “yuh ain’t gonna get to know Brooklyn wit no map,” I says.

“Can you swim?” he says, just like dat. Jesus! By dat time, y’know, I begun to see dat duh guy was some kind of nut. He’d had plenty to drink, of course, but he had dat crazy look in his eye I didn’t like. “Can you swim?” he says.

“Sure,” I says. “Can’t you?”

“No,” he says. “Not more’n a stroke or two. I neveh loined good.”

“Well, it’s easy,” I says. “All yuh need is a little confidence. Duh way I loined, me older bruddeh pitched me off duh dock one day when I was eight yeahs old, cloes an’ all. ‘You’ll swim,’ he says. ‘You’ll swim all right—or drown.’ An’, believe me, I swam! When yuh know yuh got to, you’ll do it. Duh only t’ing yuh need is confidence. An’ once you’ve loined,” I says, “you’ve got nuttin’ else to worry about. You’ll neveh forgit it. It’s somp’n dat stays with yuh as long as yuh live.”

“Can yuh swim good?” he says.

“Like a fish,” I tells him. “I’m a regular fish in duh wateh,” I says. “I loined to swim right off duh docks wit all duh odeh kids,” I says.

“What would yuh do if yuh saw a man drownin’?” duh guy says.

“Do? Why, I’d jump in an’ pull him out,” I says. “Dat’s what I’d do.”

“Did yuh eveh see a man drown?” he says.

“Sure,” I says. “I see two guys—bot’ times at Coney Island. Dey got out too far, an’ neider one could swim. Dey drowned befoeh anyone could get to ’em.”

“What becomes of people after dey have drowned out heah?” he says.

“Drowned out where?” I says.

“Out heah in Brooklyn.”

“I don’t know whatcha mean,” I says. “Neveh hoid of no one drownin’ heah in Brooklyn, unless you mean a swimmin’ pool. Yuh can’t drown in Brooklyn,” I says. “Yuh gotta drown somewhere else—in duh ocean, where dere’s wateh.”

“Drownin’,” duh guy says, lookin’ at his map. “Drownin’.”

Jesus! I could see by den he was some kind of nut, he had dat crazy expression in his eyes when he looked at you, an’ I didn’t know what he might do. So we was comin’ to a station, an’ it wasn’t my stop, but I got off anyway, an’ waited for duh next train.

“Well, so long, chief,” I says. “Take it easy, now.”

“Drownin’,” duh guy says, lookin’ at his map. “Drownin’.”

Jesus! I’ve t’ought about dat guy a t’ousand times since den an’ wondered what eveh happened to ’m goin’ out to look at Bensenhoist because he liked duh name! Walkin’ aroun’ t’roo Red Hook by himself at night an’ lookin’ at his map! How many people did I see get drowned out heah in Brooklyn! How long would it take a guy wit a good map to know all deh was to know about Brooklyn!

Jesus! What a nut he was! I wondeh what eveh happened to ’m, anyway! I wondeh if someone knocked him on duh head, or if he’s still wanderin’ aroun’ in duh subway in duh middle of duh night wit his little map! Duh poor guy! Say, I’ve got to laugh, at dat, when I t’ink about him! Maybe he’s found out by now dat he’ll neveh live long enough to know duh whole of Brooklyn. It’d take a guy a lifetime to know Brooklyn t’roo an’ t’roo. An’ even den, yuh wouldn’t know it all. ♦