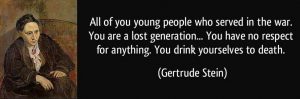

The Lost Generation is a term sometimes used for the post-World War I generation overall, but more frequently it refers to a group of American writers who became adults during or shortly after World War I. They established their literary reputations in the 1920s and 1930s. In France, these writers were sometimes referred to as Génération du feu, the “(gun)fire generation.”

Gertrude Stein is credited for coining the term Lost Generation, but Ernest Hemingway made it widely known. According to Hemingway’s A Moveable Feast (1964), Stein had heard it used by a garage owner in France, who dismissively referred to the younger generation as a “génération perdue.” In conversation with Hemingway, she turned that label on him and declared, “You are all a lost generation.” He used her remark as an epigraph to The Sun Also Rises (1926), a novel that captures the attitudes of a hard-drinking, fast-living set of disillusioned young expatriates in postwar Paris.

The generation was “lost” in the sense that it dismissed the values of the older generation no longer relevant in the postwar world. Though the change in artistic expression took place in many creative outlets and focused in several regions, the “Lost Generation” is generally used to refer in particular to American writers living in Paris between the World Wars. Many of these authors felt an alienation from a United States that, under Pres. Warren G. Harding’s “back to normalcy” policy, seemed to these writers to be hopelessly provincial, materialistic, and emotionally barren.

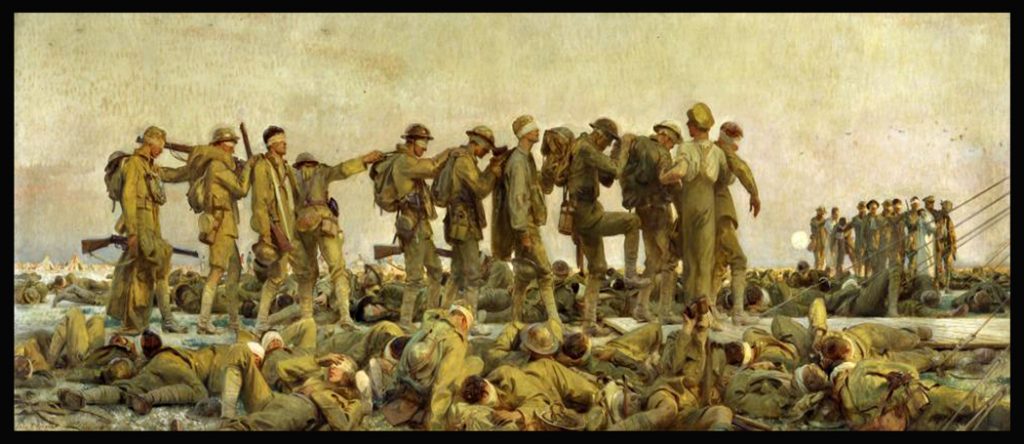

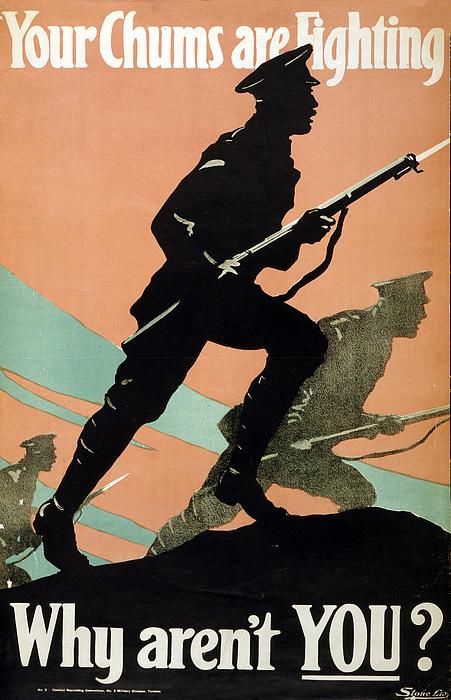

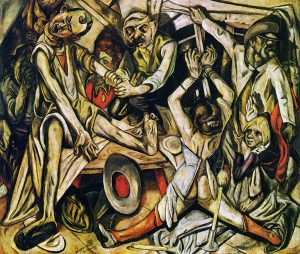

The First World War was the first time in history that chemicals and machines capable of inflicting mass carnage were widely used. Instead of charges and sorties like “The Charge of the Light Brigade,” infantry soldiers in trench warfare spent weeks at a time in close quarters with the bodies of their former allies, following futile battle strategies designed for previous wars and weapons. Having seen pointless death on such a huge scale, many lost faith in traditional values like courage, patriotism, and masculinity. Some in turn became aimless, reckless, and focused on material wealth, unable to believe in abstract ideals.

This change in values and social expectations is reflected in the language used by authors between the World Wars. Paul Fussel, author of The Great War and Modern Memory (Fussell, Paul, 1924-2012. © Oxford University Press.) illustrates the difference between “raised, essentially feudal language” used before the War and the more prosaic vocabulary used after. Foe became enemy; perish became die; warrior became soldier; vanquish became conquer; assail became attack; ashes or dust became dead bodies.

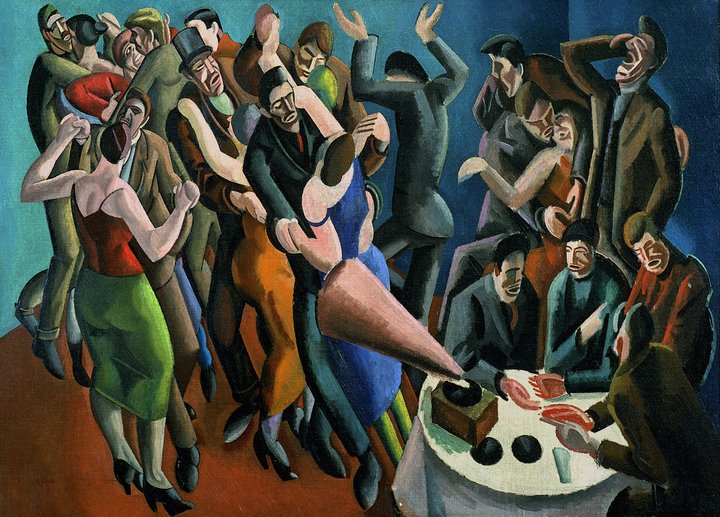

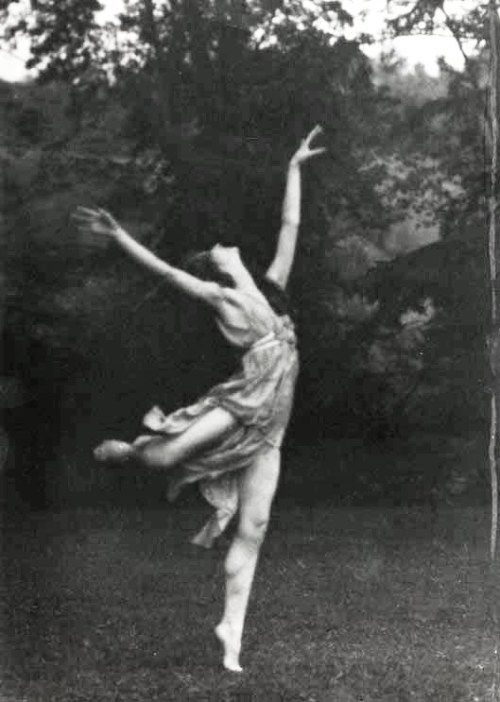

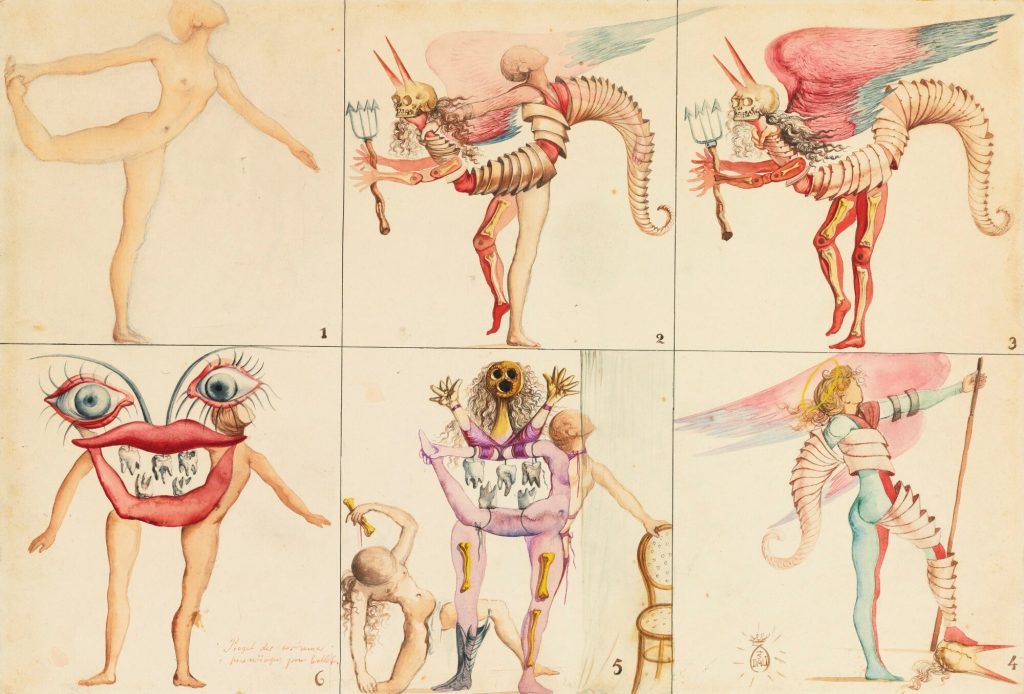

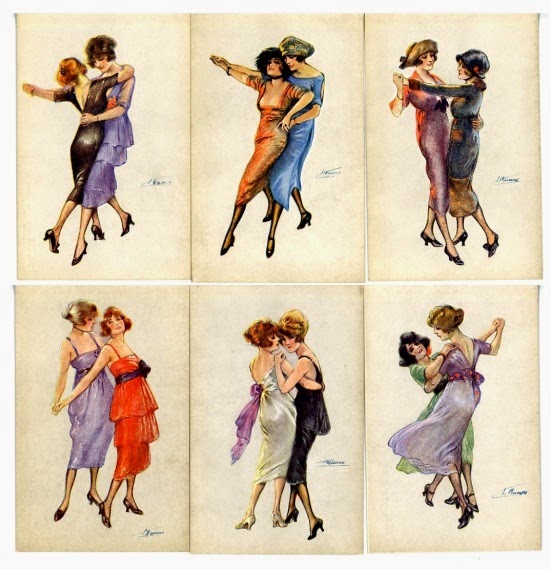

Everything that was traditionally structured or confining was stripped, allowing artists of all sorts to build new styles. Composers wrote without the usual chord progressions and cadences; they experimented with new types of ensembles or juxtaposed odd instruments. Dancers took off their pointe shoes and combined ballet with folk styles from India and South America. Women cut their hair short and loosened their corsets.

Isadora Duncan

Dorothy Parker

Early Drag Queen

The “Harlem Hellfires” of the 369th Infantry Regimen are often credited with bringing jazz to Paris in between truly impressive military feats.

In 1920, F. Scott Fitzgerald had a big year: he published his debut novel, This Side of Paradise, his first collection of short fiction, Flappers and Philosophers and his story “Bernice Bobs Her Hair” was published in The Saturday Evening Post that May.

The term embraces Gertrude Stein, Ernest Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald, John Dos Passos, E.E. Cummings, Archibald MacLeish, Hart Crane, T.S. Eliot, and other writers who made Paris the center of their literary activities in the 1920s. They were acquainted and crossed each other in Europe, but often had rocky relationships.

Kate O’Connor (Lost Generation by Kate O’Connor, licensed as Creative Commons BY-NC-SA (2.0 UK) identified three themes of Lost Generation work. I quote her here.

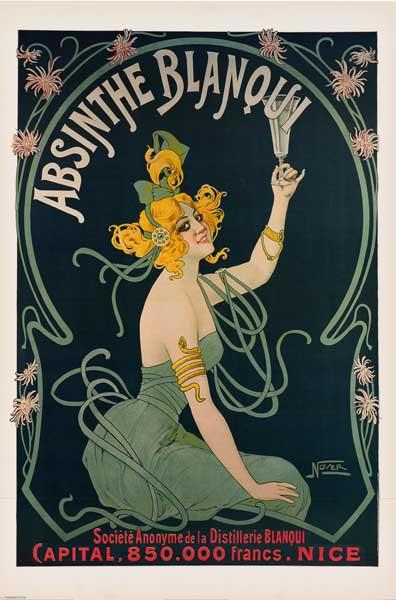

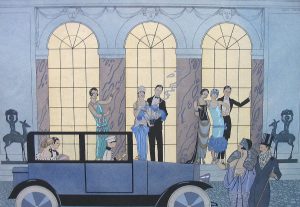

Decadence – Consider the lavish parties of James Gatsby in Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby or those thrown by the characters in his Tales of the Jazz Age. Recall the aimless traveling, drinking, and parties of the circles of expatriates in Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises and A Moveable Feast. With ideals shattered so thoroughly by the war, for many, hedonism was the result. Lost Generation writers revealed the sordid nature of the shallow, frivolous lives of the young and independently wealthy in the aftermath of the war.

Gender roles and Impotence – Faced with the destruction of the chivalric notions of warfare as a glamorous calling for a young man, a serious blow was dealt to traditional gender roles and images of masculinity. In The Sun Also Rises, the narrator, Jake, literally is impotent as a result of a war wound, and instead it is his female love Brett who acts the man, manipulating sexual partners and taking charge of their lives. Think also of T. S. Eliot’s poem The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock, and Prufrock’s inability to declare his love to the unnamed recipient.

Idealised past – Rather than face the horrors of warfare, many worked to create an idealised but unattainable image of the past, a glossy image with no bearing in reality. The best example is in Gatsby’s idealisation of Daisy, his inability to see her as she truly is, and the closing lines to the novel after all its death and disappointment: “Gatsby believed in the green light, the orgastic future that year by year recedes before us. It eludes us then, but that’s no matter- to-morrow we will run faster, stretch our arms farther… And one fine morning— So we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past.”

Kirk Curnutt, author of several books about the Lost Generation writers suggested that they were expressing mythologized versions of their own lives.

In an interview for The Hemingway Project, Curnutt said: “They were convinced they were the products of a generational breach, and they wanted to capture the experience of newness in the world around them. As such, they tended to write about alienation, unstable mores like drinking, divorce, sex, and different varieties of unconventional self-identities like gender-bending.”

Bottom line for writers: it’s been 100 years, but their work shouldn’t be lost. There’s a lot of good stuff here. Find yourself a Lost Generation writer to enjoy.