What did people do before calendars? Clearly, they were always aware of seasons.

Architectural Calendars

I’m amazed by the sophisticated calculations and understanding of ancient cultures.

Stonehenge, for example. It is 4,000 to 5,000 years old, and consists of a ring of massive standing stones, some weighing up to 25 tons (which speaks to amazing engineering achievements, as well). Stonehenge is widely believed to have been used for ceremonial or religious purposes. It aligns with the solstices, especially the summer solstice sunrise and winter solstice sunset. This may hint at its use as an ancient astronomical calendar.

The Inca people also tracked the solar year. They built intihuatana stones (meaning “hitching post of the sun”), such as the famous one at Machu Picchu. Incas used these as solar clocks or calendars to mark solstices and equinoxes. The solstices (around June 21 and December 21) were critical for marking agricultural cycles and religious festivals. The Inca calendar was primarily solar, with 12 months of 30 days each, plus 5 extra days to complete the year. Each month was linked to specific agricultural or ritual activities, often dictated by astronomical observations. For example, the rising of the Pleiades star cluster (known as Qollqa) marked the time to begin planting potatoes and other crops.

Varieties of Native American Calendars

Native Americans tracked the year in numerous ways. I’m especially interested in Native American life, so I’ll go into a bit more detail.

Many peoples tracked the year using moon-based and seasonal cues/events, starting in spring, sometimes counting 4, 5, 12, or 13 moons, and occasionally adding an extra moon every few years to align with solar years. The Lakota also used winter counts (waniyetu wówapi) with pictographic records of notable events and environmental observations to mark each year.

Cycle Tracking

Native American groups tracked the year by observing natural cycles.

- Changing seasons: They noted the progression of spring, summer, fall, and winter through environmental changes like plant blooming, animal migrations, and weather patterns.

- The Ojibwe divide the year into five seasons: Ziigwan (spring), Niibin (summer), Dagwaagi (fall), Biboon (winter), and Minookimi, a season between midwinter and spring.

- Phenology: The timing of natural events, such as when certain plants flowered or when specific animals appeared or migrated, served as natural calendars.

- Members of the Menominee tribe are using historical phenology to study the effects of climate change on fruit ripening speed and amounts.

- Harvest cycles: Key agricultural events like planting and harvesting corn, beans, and squash marked important yearly milestones.

- The Mississippian people mark the New Year with fasting and feasting at the Green Corn Puskita Ceremony.

Lunar Counting

Many tribes used the phases of the moon to mark time.

- A lunar cycle (about 29.5 days) was often counted, with 12 or 13 lunar cycles roughly corresponding to a year.

- Each full moon often had a specific name reflecting the time of year or natural phenomena. For example, the “Strawberry Moon” in early summer when strawberries ripened, and the “Harvest Moon” in autumn during the main harvest period.

- The Anishinaabe people named each moon to correspond with natural events: January, Moon of the Hardening Ice; May, Flowering Moon; October, Falling Leaves Moon.

- The Mashantucket Pequot people have thirteen moons, often named for activities performed during that month. For example, the Corn Planting Moon and the Gift Giving Moon.

- These moon names helped organize activities and ceremonies.

Solar Counting

Some tribes created calendars by observing the sun’s position and its cycles.

- Solstices and equinoxes were important markers. For example, many people have celebrated the winter solstice as the rebirth of the sun.

- The Mississippian people constructed a series of timber circles in Illinois. The red cedar posts at Cahokia line up with summer and winter solstices as well as both equinoxes.

- Some people built structures like medicine wheels or stone alignments to track solar events.

- The Big Horn Medicine Wheel (Annáshisee) in Wyoming is at least ten thousand years old. According to the Crow people, it was already present when they came to the area. Archaeologists theorize that prehistoric ancestors of the Assinniboine people may have constructed it to mark solar alignments.

Some tribes used counting systems based on days or moons. For instance, the Lakota counted years by the number of winters or summers passed.

Chinese Calendars

The Chinese calendar is a traditional system people have used in China and many East Asian cultures. It combines both lunar and solar elements, making it distinct from the purely solar Gregorian calendar commonly used worldwide today.

Modern-day China uses the Gregorian calendar for most purposes. However, for holidays and selecting auspicious dates, people still use the traditional Chinese lunisolar calendar.

Key Features of the Chinese Calendar:

Chinese New Year: The most famous date, the Lunar New Year, falls on the second new moon after the winter solstice, typically between January 21 and February 20.

Lunisolar System: It tracks months based on the moon’s phases (lunar months) but also aligns with the solar year to keep seasons consistent.

Months: Each month begins with a new moon and lasts about 29.5 days. There are 12 months in a normal year.

Leap Months: To synchronize the lunar months with the solar year (about 365.24 days), the calendar inserts an extra (leap) month every 2-3 years, resulting in a 13-month year.

Solar Terms (节气, Jiéqì): The year is divided into 24 solar terms based on the sun’s position along the ecliptic. These mark important seasonal changes and agricultural periods.

Zodiac Cycle: The calendar features a 12-year animal cycle—Rat, Ox, Tiger, Rabbit, Dragon, Snake, Horse, Goat, Monkey, Rooster, Dog, Pig—each year associated with an animal sign.

Heavenly Stems and Earthly Branches: A 60-year cycle combining 10 Heavenly Stems and 12 Earthly Branches creates a complex naming system for years, months, days, and even hours.

Non-Gregorian Calendars Today

Whether called calendars or not, people have used multiple systems to align days, months, and years with the solar cycle.

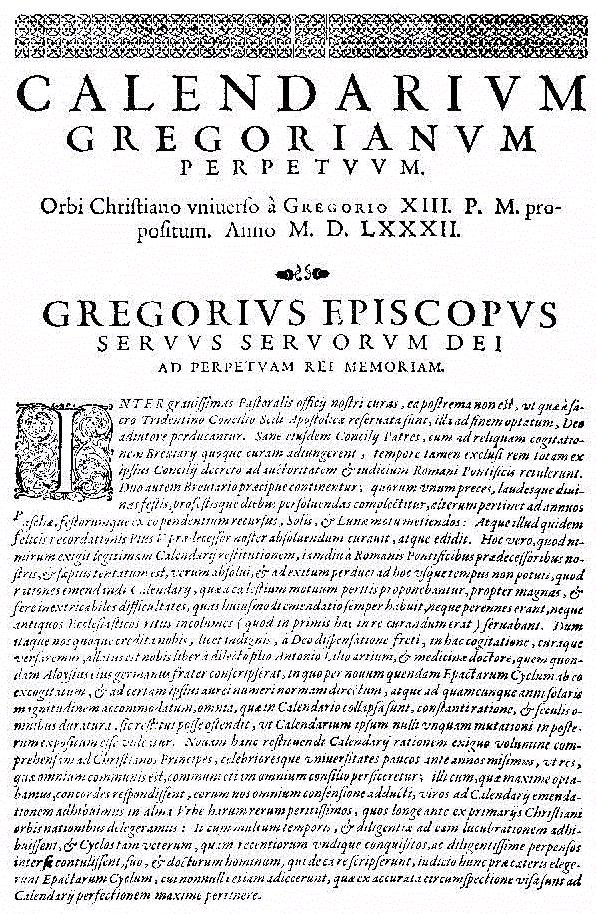

Today, when we talk about a calendar, no one doubts that we mean the Gregorian calendar. It is the calendar in use in most parts of the world. It went into effect in October 1582 following the papal bull Inter gravissimas issued by Pope Gregory XIII, which introduced it as a modification of, and replacement for, the Julian calendar. The principal change was to space leap years slightly differently to make the average calendar year 365.2425 days long (rather than the Julian calendar’s 365.25 days). This more closely approximates the 365.2422-day “tropical” or “solar” year that is determined by the Earth’s revolution around the Sun. Tiny tweak, but apparently really significant.

Although the Gregorian Calendar is virtually universal for civic purposes, people continue to use many other calendars for religious or cultural purposes.

Here are some of these calendar comparisons, and how they would have marked the same date:

- Gregorian calendar: 30 December, AD 2025

- Islamic (ٱلتَّقْوِيم ٱلْهِجْرِيّ Hijri) calendar: 10 Rajab, AH 1447 (using tabular method)

- Solar (ڕۆژژمێری کۆچیی ھەتاوی Hijri) calendar: 9 Dey, SH 1404

- Hebrew calendar (הַלּוּחַ הָעִבְרִי HaLuakh ha’Ivri): 10 Tevet, AM 5786

- Coptic calendar: 21 Koiak, AM 1742

- Bengali calendar (বঙ্গাব্দ Bôṅgābdô): 15 Poush, BS 1432

- Ethiopian calendar (ዐውደ ወርኅ Geʽez): 20 Tahsas, 2019

- Julian calendar: 17 December, AD 2025

And sometimes people use calendars in idiosyncratic ways. A well-traveled friend of mine said, “When I lived in Georgia [the country], people took advantage of the difference between the Gregorian and Julian calendar to celebrate Christmas twice: on December 25th and again on January 7th!”

Bottom Line: People have always tracked the progress of the year in whatever ways served their times and lives.