I have chiro—a chiropractic manipulation—every four weeks, and have done so for years. On my way to my most recent appointment, I decided to write a blog about “bone doctors.” But after talking with my practitioner, I decided to focus on only one bone doctor specialty, chiropractic medicine.

By most estimations, DCs (Doctors of Chiropractic) treat over 35 million Americans annually—adults, children, even infants.

To put it another way, more than one million chiropractic adjustments happen every day.

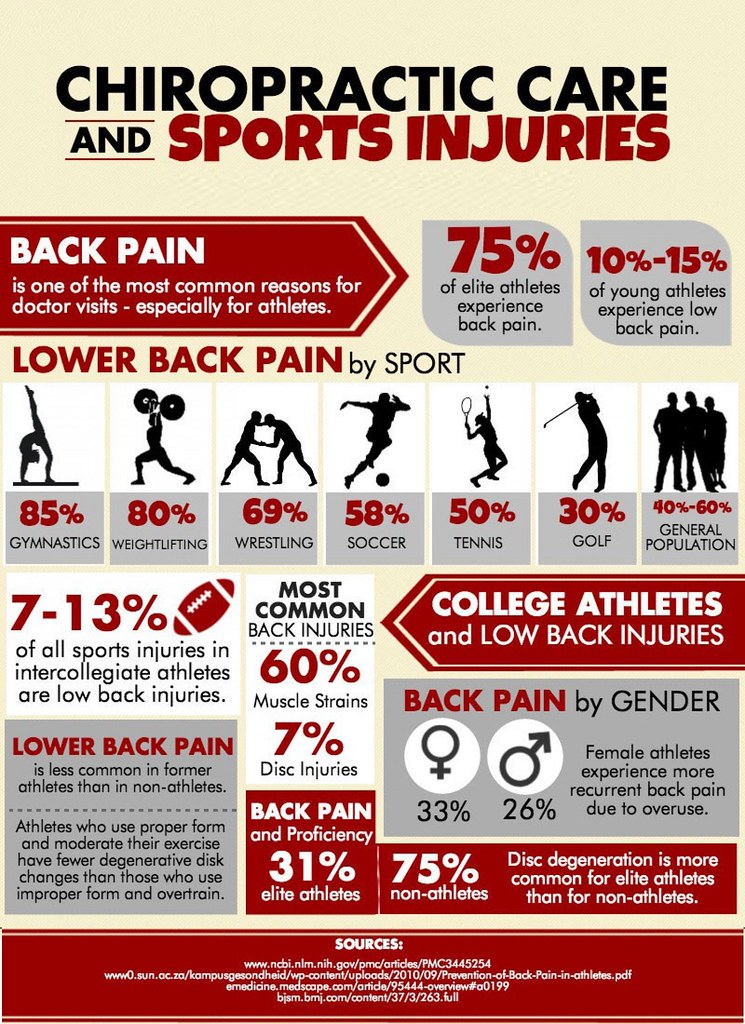

I get a monthly adjustment because of pain in my back and shoulders. (Because of the hours I hunch over a laptop, perhaps.) Chiropractic treatment is used to treat a a lot more than my type of issues, of course, including headaches, whiplash, strains and sprains, sports injuries, arthritis, and more.

Who Sees a Chiropractor?

In general, people experiencing chronic pain or musculoskeletal issues are most likely to seek the services of a chiropractor. Some sources say that’s adults aged 31 to 64, while others put the ages between 45 and 64. Among younger patients, the majority are between 12 and 17. Well over half of chiropractic patients are female, sixty percent to be exact.

My chiropractor said that he sees more people who work in the financial sector than day laborers such as ditch diggers. Go figure.

Another sector that relies on chiropractors is athletics. All 32 NFL teams have their own chiropractor(s) to boost performance, maintain wellness, and treat musculoskeletal strain and injury. Many professional dance companies include a chiropractor among the medical staff.

Chiropractic is especially popular among people seeking natural solutions for pain, injury recovery, sports performance, and preventive wellness—especially those looking to avoid surgery or medication.

Chiropractic History

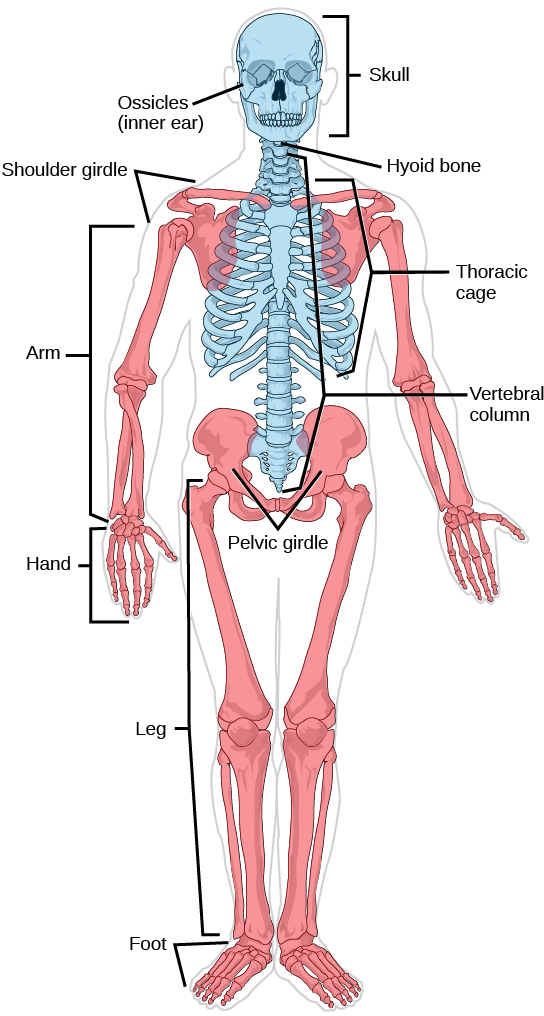

Hippocrates, who is often called the Father of Modern Medicine, as far back as 450 BCE, wrote, “Look Well To The Spine For The Cause Of Disease.”

Hippocrates also said that the function of the skeleton and the spine is to form the shape of the body and keep us upright.

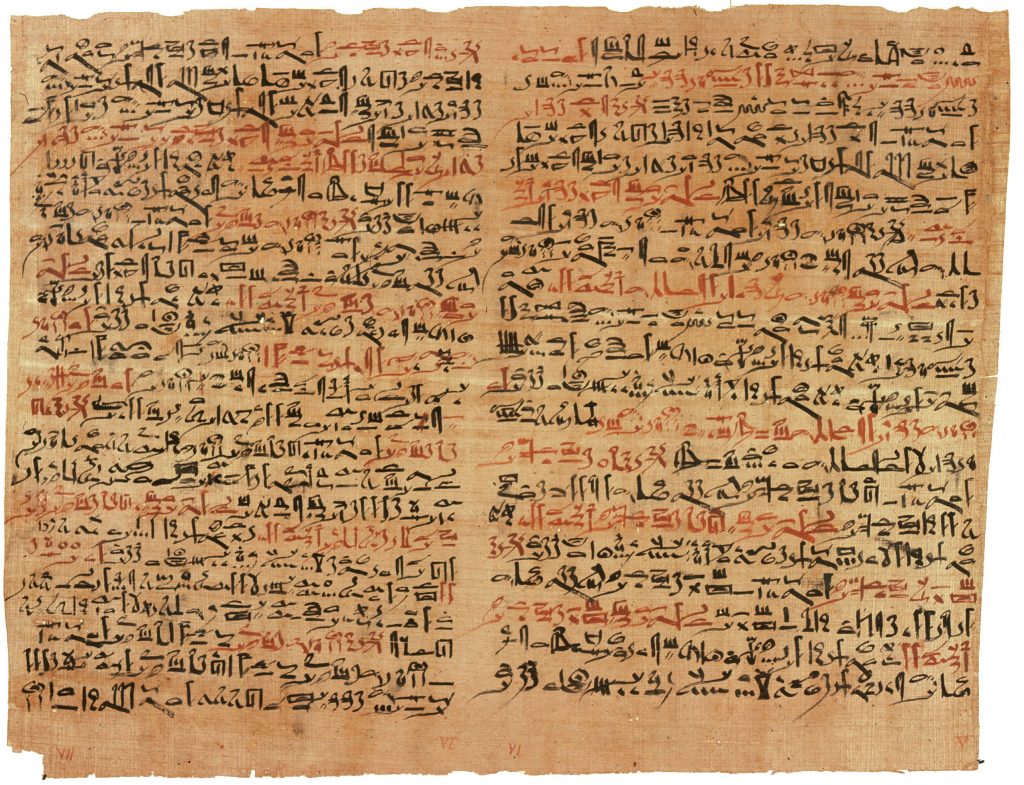

However, joint manipulation predated Hippocrates. The oldest known medical text, the Edwin Smith papyrus of 1552 BCE mentions joint manipulation. The text describes the Ancient Egyptian treatment of bone-related injuries.

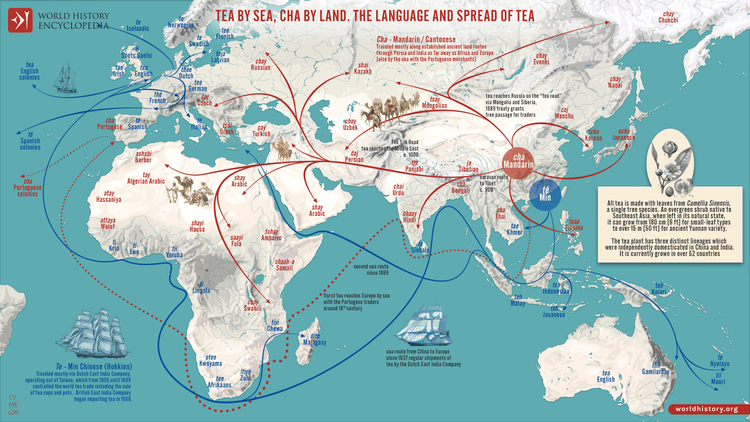

The term “chiropractic” derives from two Greek words: cheir which means hand, and praktos which means done, thus “Done by Hand.”

Early Chiropractors

Nevertheless, according to every source I found, chiropractors trace their roots to 1895, when Daniel David Palmer (the father of chiropractic!) helped Harvey Lillard by accidentally performing what is now known as a chiropractic adjustment.

I find the story of Palmer’s first patient pretty interesting. Unusual for that time, Harvey Lillard, an African American man, owned a cleaning company. By chance, his company serviced the building where Palmer was practicing magnetic healing.

The two were chatting one day, and Palmer noticed that Lillard had a vertebrae that was out of place. Lillard told Palmer that, about seventeen years prior, while picking up a wagon wheel he heard a pop in his neck and immediately lost his hearing.

Palmer examined Lillard’s neck and found what is now referred to as a subluxation, a vertebrae that is out of place. Palmer deduced that this was the cause of Harvey’s deafness, and thought he could fix the issue by moving that vertebra back into position. Immediately, Harvey said he could hear the “racket on the streets.” Word spread about the “cure,” and before long people were coming to Palmer from all over the place.

Lillard’s daughter remembers a different story of his treatment. According to her account, Palmer slapped her father on the back while laughing at a joke. A few days later, her father’s hearing improved. This inspired Palmer to investigate spinal manipulations as a method of treating illnesses.

According to Palmer’s own testimony, he wrote The Chiropractor’s Adjuster by means of spiritist messages from deceased physician Dr. Jim Atkinson. In fact, Palmer saw his new medical treatment as quasi-religious in nature, arguing against anyone who would “interfere with the religious duty of chiropractors, a privilege already conferred upon them. It now becomes us as chiropractors to assert our religious rights.”

Daniel David Palmer’s School

Two years later, Palmer started the first school of chiropractic, the Palmer School and Cure. This first school is still active today (renamed to Palmer College of Chiropractic), a leader in chiropractic education.

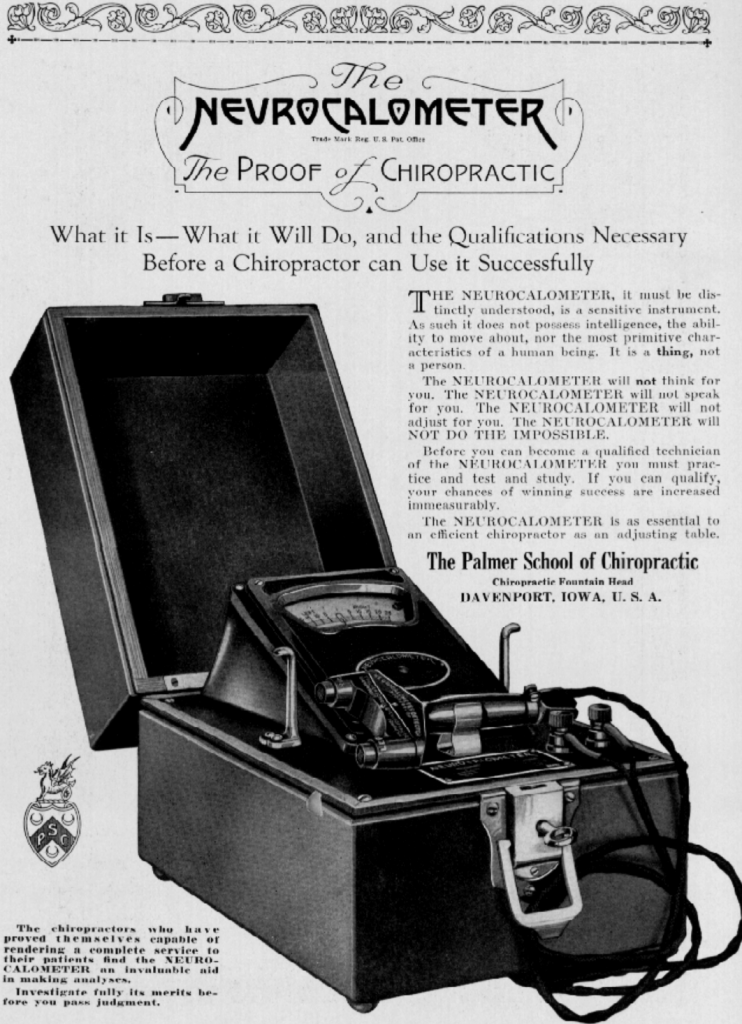

And talk about nepotism! Daniel David Palmer passed his interest in chiropractic to his son, DCBartlett Joshua (B.J.) Palmer. B.J. Palmer, known as “The Developer”, took chiropractic to the next level. He inherited his father’s practice and eventually took over the renamed Palmer College, where he added science, philosophy, and technique to the art of spinal adjustment. Under B.J.’s leadership, chiropractic care spread internationally and was positioned as a unique and vitalistic healthcare profession.

Unlike his father’s position that chiropractic medicine was a nearly religious calling, B.J. Palmer saw the school as a commercial operation. He said it was, “…a business, not a professional basis. We manufacture chiropractors. We teach them the idea and then we show them how to sell it.”

B.J. also introduced x-rays to chiropractic diagnostics in 1910—a controversial yet revolutionary decision at the time. He built a chiropractic research clinic and purchased a local radio station (WOC) to provide nationwide broadcasts promoting health. In fact, Palmer hired rookie reporter Ronald Reagan, in his first broadcast job, to read sports for WOC.

His emphasis on the “above-down, inside-out” healing philosophy laid the foundation for the modern chiropractic worldview.

B.J.’s son, DC David D. Palmer also became involved. The fourth generation of Palmers, David’s daughters, are still active in the school today, and have all served the college or sat on its board of trustees.

The Palmer College now has campuses in Florida and California and offers cutting-edge training in everything from spinal biomechanics to functional neurology.

One of the foundational philosophies of chiropractic is Innate Intelligence—the idea that the body has a natural ability to heal itself when the nervous system is functioning without interference. Subluxations, or spinal misalignments, can block this natural healing ability.

This concept was central to D.D. and B.J. Palmer’s chiropractic philosophy and continues to guide many practitioners today. When the spine is aligned and the nervous system is clear, the body’s innate wisdom can restore balance and function.

Chiropractic Law

Chiropractors were once jailed for practicing medicine without a license. In the early 1900s, chiropractic was not recognized as a licensed health profession in most U.S. states because they didn’t prescribe drugs or perform surgery. In 1906, D. D. Palmer spent 17 days in jail rather than pay a fine for practicing medicine without a license in Iowa. He considered classifying chiropractic as a religion to avoid the new Iowa medical licensing law.

Dr. Herbert Ross Reaver was arrested over 70 times in Ohio between the 1930s and 1950s simply for practicing chiropractic. Dr. Reaver and other activists fought for legal recognition of chiropractic, eventually leading to licensure in all 50 states and in over 90 countries.

After decades of lobbying and advocacy, Louisiana became the final U.S. state to license chiropractic in 1974, officially recognizing chiropractic as a legitimate healthcare profession.

Even so there was still an aura of less-than clinging to chiropractors. In the 1960s, the American Medical Association (AMA) historically labeled chiropractic as “quackery.” In fact, in 1963, the AMA formed a “Committee on Quackery” with the goal of discrediting and eliminating chiropractic.

Chiropractors were barred from hospital privileges, referrals, and insurance reimbursements, and were ridiculed publicly.

However, chiropractors fought back! In 1987, a historic legal case—Wilk v. AMA— found that the AMA had unlawfully conspired to undermine the chiropractic profession. This landmark decision helped establish chiropractic as a legitimate, independent healthcare practice.

Today, chiropractors often work alongside MDs, DOs, and physical therapists as part of integrative health teams.

Chiropractors Today

Doctors of Chiropractic (DCs) go through a minimum of 4,200 hours of classroom, lab and clinical internships during their 4-year doctoral graduate school program, including lab and clinical work. Internships must be completed during a doctoral program, within four years. These standards are set by the National Board of Chiropractic Examiners. Individual states often have their own rules and regulations.

Chiropractic is recognized and regulated by law in over 49 countries. And in the United States, DCs are licensed in all 50 states!

The VA passed legislation allowing chiropractic treatment in VA medical facilities back in 1999. Today, 70 VA hospitals offer chiropractic treatments for rehabilitation and prosthetic services.

There are roughly 100,000 chiropractors in active practice around the world and over 70,000 here in the U.S. About 10,000 students are currently enrolled in chiropractic education programs in the United States.

Chiropractic treatments are extremely safe. In fact, out of hundreds of thousands of patients, less than 50 known injuries have been recorded—making it safer than treatments by primary care doctors.

Who Benefits?

Each day, over one million adjustments take place across the globe. That’s a whole lot of relief!

Chiropractors are the top rated medical professionals for treating lower back pain. Over three-quarters of chiropractic patients—77 percent, to be exact—feel that the treatment they received was very effective.

Analysis from a large chiropractic network dataset shows that 80.24% of patients who receive chiropractic care typically see significant improvement in their condition within one month of starting treatment.

Injured workers are a whopping 28 times less likely to need surgery if they go to a chiropractor first, rather than a doctor.

Chiropractors can provide relief to pregnant women. In fact, some chiropractors have undergone special training and focus on helping women cope with the strains and stresses that growing a baby puts on the body. (If only I’d known this decades ago!) Misalignments in the pelvis can reduce the amount of space the baby has in the womb and can also cause complications with delivery. Aside from that, chiropractic treatment can help reduce nausea, relieve back and neck pain, and even reduce the chances of having to deliver by C-section.

Unbeknownst to many, infants can benefit greatly from the care of a chiropractor. It makes sense—birth can be pretty hard on a little body! The adjustment is adapted to suit their needs, but chiropractic treatment on children under age 2 is banned in many countries.

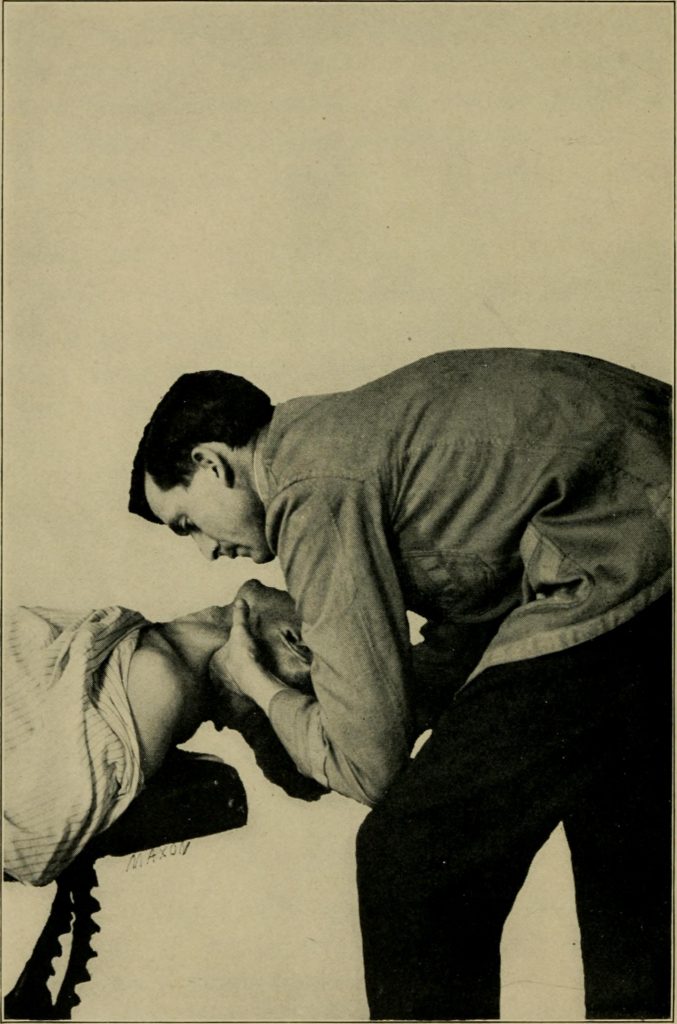

Chiropractic Methods

Modern chiropractors combine traditional hands-on techniques with high-tech tools, such as digital x-rays, thermal scans, EMG scans, and postural analysis software to provide safe, effective care. Research continues to validate chiropractic’s effectiveness for conditions like low back pain, neck pain, headaches, sciatica, and joint dysfunction.

Treatment for low back pain initiated by a DC costs up to 20 percent less than when started by a medical doctor. Patients save about $83.5 million a year by going to a chiropractor instead of an MD for chronic back pain. In addition, chiropractic care lowers pharmaceutical costs by as much as 58%.

An injured worker is 28 times less likely to have spinal surgery if the first point of contact is a DC rather than a surgeon.

Chiropractic care relies upon conservative natural treatments. Although chiropractors do not prescribe drugs or perform surgery, they work with other healthcare professionals to provide comprehensive care.

In addition, chiropractors offer soft tissue therapy, rehabilitation exercises, and lifestyle and nutritional counseling.

Bottom Line: Chiropractors are extensively trained to provide safe, effective care focused on musculoskeletal health and holistic wellness.