Happy half-hour was typically celebrated with our workshop group, followed by dinner during which we dispersed among the other writers present. Then we adjourn to the renovated Rec Hall for 8:00 readings. On Sunday night, Cathy Hankla and Sheri Reynolds read and Charlotte Morgan gave us our marching orders about the week’s structure.

I’m honored to be interviewed on Fiona Quinn’s Thrill Writing, a blog helping thriller writers write it right.

We talk about why a character might act “out of character,” group mentality, behavior matching, why people might be more passive in groups or more likely to riot, and more.

In this article, we’re talking about what happens to a character when they get into a group where a character might act “out of character”, which is a fun way to develop the plot.

Can you first give us a working definition for “group”

Vivian – We usually think three or more, but some “group” effects are present even with only two. Also, the “group” needn’t be physically present to exert influence.

Fiona – Can you explain that last sentence?

Vivian – Some group memberships are literal memberships–for example, a church congregation, sorority, bridge club, etc. such groups are often in our thoughts, and serve as a reference or standard for behavior even when the member is alone.

Fiona – Does “group mentality” work both ways? For example, people in a riot become riotous, but people in a disaster, where they see all hands on deck, become heroes?

People in a religious forum feel more religious. . .sort of like a magnifier?

Vivian – Absolutely. I just mentioned formal groups–which are the ones having the strongest influence at a distance– but crowds, mobs, any physical gathering of people, shapes our behavior to act or remain passive.

Fiona – Can you give us a short tutorial on what we need to know about group dynamics to help write our characters right?

Vivian – Well, there is a phenomenon known as behavior matching, a tendency to do what others around us are doing. This is reflected in everything from eating to body language. Even a person who has eaten his or her fill will eat more if someone else comes in and starts eating. If others are slouching, your character isn’t likely to remain formal.

Fiona – Yes, it’s hard to pass up a piece of chocolate cake when everyone else is moaning about how delicious it tastes.

Just sayin’

Vivian – A related phenomenon–I suppose it could be a subset of behavior matching– has the label diffusion of responsibility. This is the tendency for people to stand passively by when others are present. There was a classic case, decades ago, in which a NYC woman named Kitty Genovese was murdered in the courtyard of her apartment. The murder took approximately half an hour, and dozens of her neighbors watched from their windows. No one came to help or even called the police. The more people who could help, the less likely anyone will take responsibility for doing so.

And then there is group disinhibition. This is sort of the opposite. It is that people are more likely to take risks, break the law, be violent when others are doing so. Think looting, or harassing a homeless person. Disinhibition is even more powerful when alcohol is involved. I recently posted a blog on alcohol for writers that goes into that a bit.

But the bottom line is that we behave differently with others present than when alone.

Thank you, Fiona!

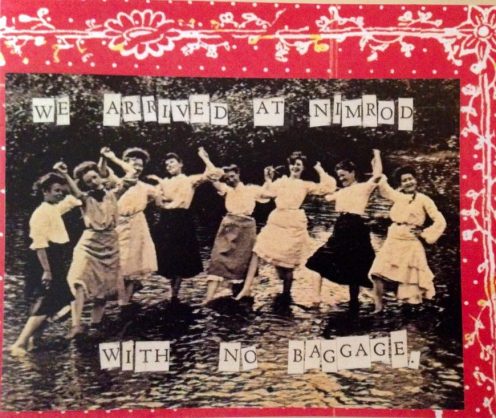

For many years I’ve traveled to Nimrod Hall in Millboro, Virginia, for their annual writing retreat. Nimrod has inspired several of my stories and given me hours of valuable writing time.

Last year I kept a travel log of my two weeks at Nimrod. I shared everything from packing my bags…

…to the wild women writers I met there.

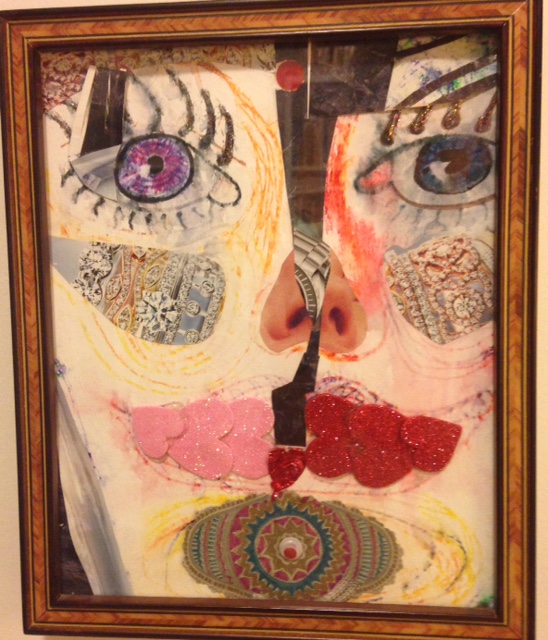

As I prepare to depart, I look forward to my misty morning walks,

and family-style meals with writer friends,

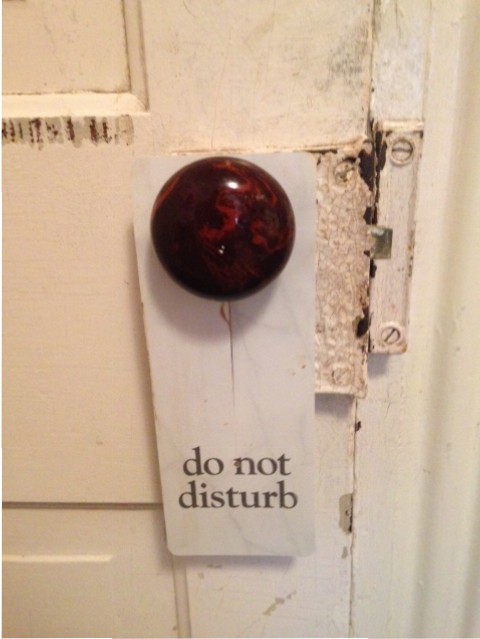

and uninterrupted writing time.

This year I will share my travel log on my Facebook page. I hope you’ll join me there.

Happy writing!

Nimrod Hall, established in 1783, has been providing summer respite from everyday stress since 1906. It has been operating as an artist and writer colony for over 25 years. The Nimrod Hall Summer Arts Program is a non-competitive, inspirational environment for artists to create without the distractions of everyday life.

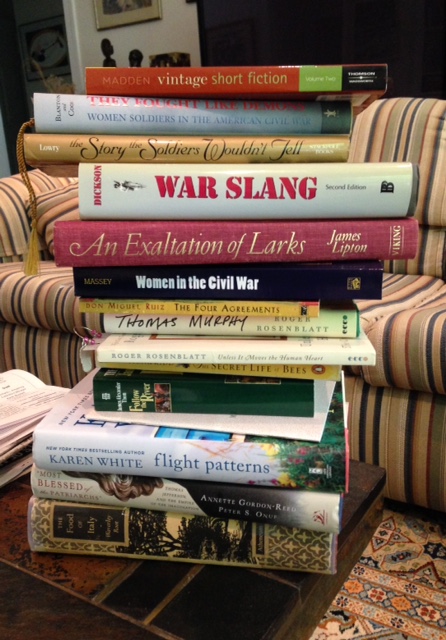

Addict: a person who has a compulsion toward some activity. Because these compulsions are often injurious, the label of addict has negative connotations. So one might instead choose alternative labels, such as aficionado, buff, devotee, enthusiast, fan, fanatic, junkie, etc.

As Erasmus once said, “When I get a little money, I buy books; and if any is left, I buy food and clothes.”

And, beware, this addiction is often passed on to one’s children and grandchildren, ad infinitum.

-Vodka sodas are for people who want to lose weight—or want people to think so—but not enough to quit drinking.-Jager bombs and vodka Red Bull are for basic bros.-Blue Moon is for craft beer posers.-Real craft beer drinkers are actually pretty cool.-Annoying people act like they invented picklebacks. (Apparently a shot of whisky followed by a shot of pickle juice—really.)-Buttery Chardonnays are for soccer moms.-Only rookies drink Appletinis.-Bud Light is for sporting events and day drinking, not Saturday night.-Martinis are a classic, classy drink.-Shots should be taken with a beer or a celebration. (Otherwise they’re for alcoholics.)

If it’s worth doing, it’s worth doing right.

Finish what you start.

If at first you don’t succeed, try again.

Failing is nothing to be ashamed of, but not trying your best is.

Go as far as you can, as fast as you can.

Education is the union card to a better life.

Your word is your bond.

Say what you mean and mean what you say.

Do unto others as you would have them do unto you.

Always be there for family.

It’s better to be the one giving help than the one receiving it.

When all is said and done, be prepared to take care of yourself and yours.

Just Because You’re Paranoid Doesn’t Mean They Aren’t Out To Get You.