Today’s blog entry was written by Kathleen Corcoran, a local harpist, writer, editor, ESL teacher, luthier, favorite auntie, duct tape sculptor, frequent ER visitor, and nosy acquaintance of medical professionals.

The human body is a complicated mess of electricity and wobbly bits, delicately balanced on a knife-edge of temperature and calories. All this pain and suffering is wonderful! …in fiction. Spectacular injuries, sudden deaths, miraculous recoveries, selfless healers all make great stories, but medicine doesn’t always oblige authors by being acceptably dramatic.

In reality, many of the most common medical scenes are impossible. People who have drowned don’t open their eyes to gaze adoringly at their rescuer giving them mouth-to-mouth resuscitation. A pregnant patient won’t feel her water break like an exploding water balloon and then go immediately into screaming contractions. The tough warrior can’t simply pull a knife from a stab wound and run back into the fray. It’s perfectly fine to wake a sleepwalker.

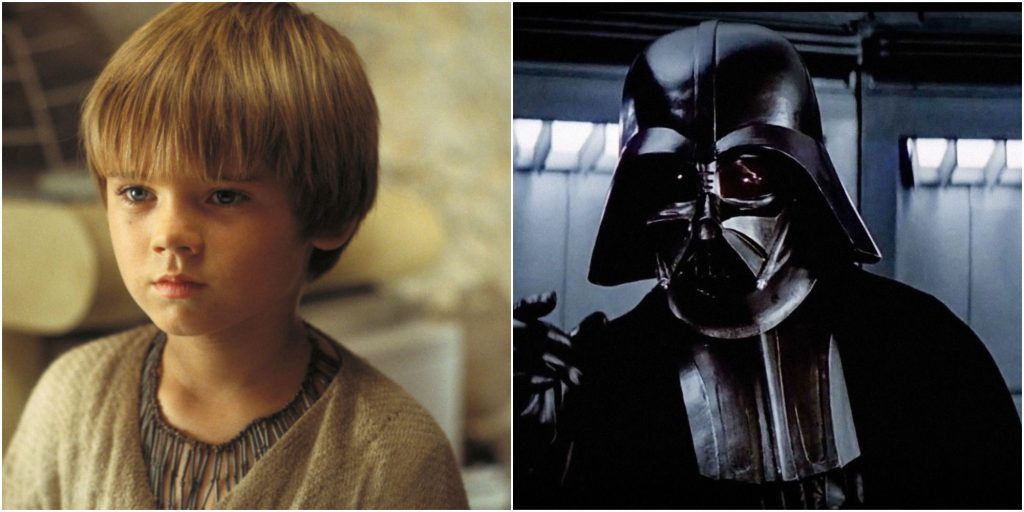

No One Comes Out of a Coma Like Sleeping Beauty

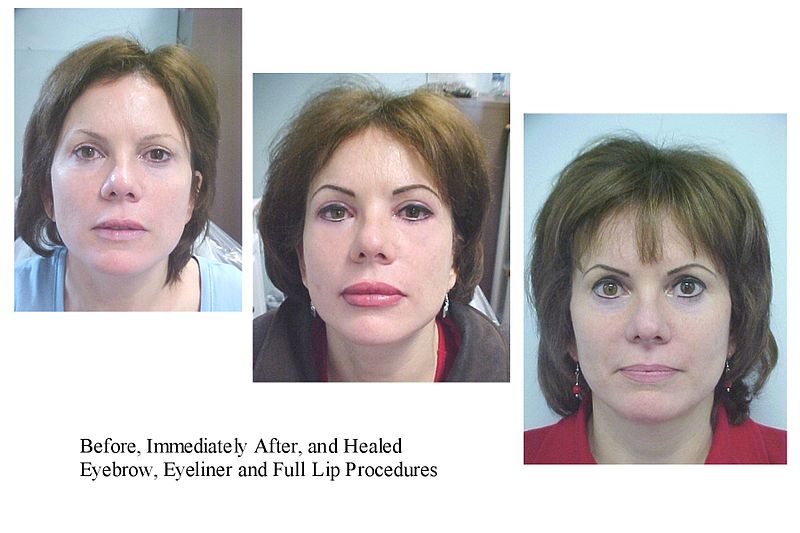

Fairy tales (and soap operas) would have us believe that a patient in a coma state will flutter their lashes and smile their way to consciousness at the most convenient moment in the plot. Of course, hair and make-up are always perfect, and any IVs or breathing tubes are just for show. Immediately, the patient is able to sit up and provide vital information to conveniently stationed witnesses.

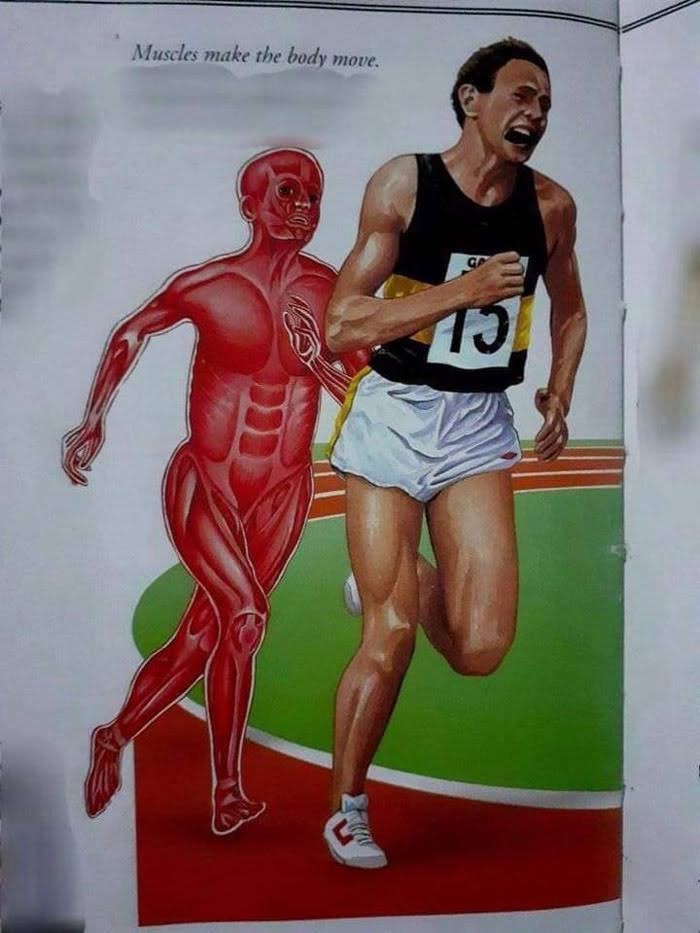

In real life, a patient comes out of a coma slowly, often over the course of hours or days. Random mumbles and muscle contractions are far more likely than eloquent confessions. Of course, that’s assuming the patient doesn’t have a breathing tube in their throat, pneumonia and bed sores from staying in one position for so long, and permanent brain damage. Any extended time in bed will result in muscle atrophy, which makes dancing around the hospital room a little difficult.

CPR Doesn’t Magically Bring People Back to Life

When someone’s heart stops beating, there is no point shocking their chest with defibrillator paddles and shouting, “Clear!” while the patient’s body jerks like a dolphin. Those scenes have plenty of tension and drama but not much medical fact.

A trained onlooker leaning over the lifeless body and thumping on the chest is a little more accurate, but the outcome is unfortunately not. Applying enough pressure on the chest to force the heart cavities to squeeze blood nearly always is also enough pressure to crack ribs. It’s an exhausting process, and the person providing CPR can’t stop. The American Red Cross no longer trains first aid providers to stop and force air into the patient’s mouth, because it is so much more important to stimulate and simulate heartbeats.

Unlike those dramatic scenes in medical dramas, real CPR scenes are frequently unsuccessful. Only 10-20% of patients undergoing CPR recover at all. Those whose hearts do resume beating on their own are likely to suffer permanent loss of function and brain damage.

People Knocked Unconscious Don’t Just Pop Back Up

Knocking characters unconscious is a very convenient way to take them out of a fight without racking up the body count. Unfortunately, it’s not very convenient to the brains of those knocked unconscious.

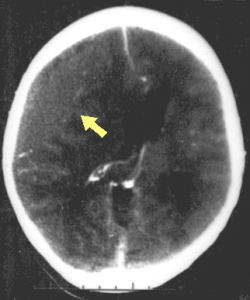

A blow strong enough to knock someone unconscious, even briefly, is strong enough to cause brain damage, possibly even skull fractures. Hematomas (bleeding into the skull) can leave scars on the brain that can be seen on X-rays years later.

Like coma patients (which head trauma patients may become), a character knocked unconscious is likely to be groggy and uncoordinated when they come to. Someone who has been repeatedly knocked unconscious might develop chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), as football players are finding out now.

Fictional Medicine Never Includes Enough Paperwork

Medical TV shows almost always show the characters taking long coffee breaks, jumping in and out of relationships, creating miraculous cures just in the nick of time, and doing everything else except practice medicine. The same rules seem to apply to nurses, technicians, radiologists, residents, EMTs, office staff, and everyone else employed in or around sick people.

What these fictional settings almost never show is the reality of medical practice: paperwork. So much paperwork. When not attending directly to patients, everyone has to dig their way out from under mountains of unending paperwork.

.

There are far more examples of medical inaccuracies than I can cover in this one post. Watching a medical professional watch TV is often more entertaining than the show itself. I have it on good authority that Scrubs and Sirens are two of the most accurate portrayals of the medical profession, despite (or perhaps because) they are both absurd comedies.

Before writing about injuries, death, doctors, nurses, medicine, pharmacists, or anyone or anything else involved in healthcare, I strongly suggest doing plenty of research or asking a medically inclined editor to take a look at what you’ve written.