Check a thesaurus for words related to inertia. You’ll find plenty of alternatives, from attitude to Newtonian physics.

- Apathy

- Indolence

- Idleness

- Languor

- Lassitude

- Laziness

- Lethargy

- Listlessness

- Oscitancy

- Passivity

- Sloth

- Deadness

- Dullness

- Immobility

- Immobilization

- Inactivity

- Paralysis

- Sluggishness

- Stillness

- Stupor

- Torpidity

- Torpor

- Unresponsiveness

Indeed, the first dictionary definition (n) is a tendency to do nothing or to remain unchanged.

If you ask a physicist (or any one in a beginning physics class) you get a less one-sided view:

Inertia noun

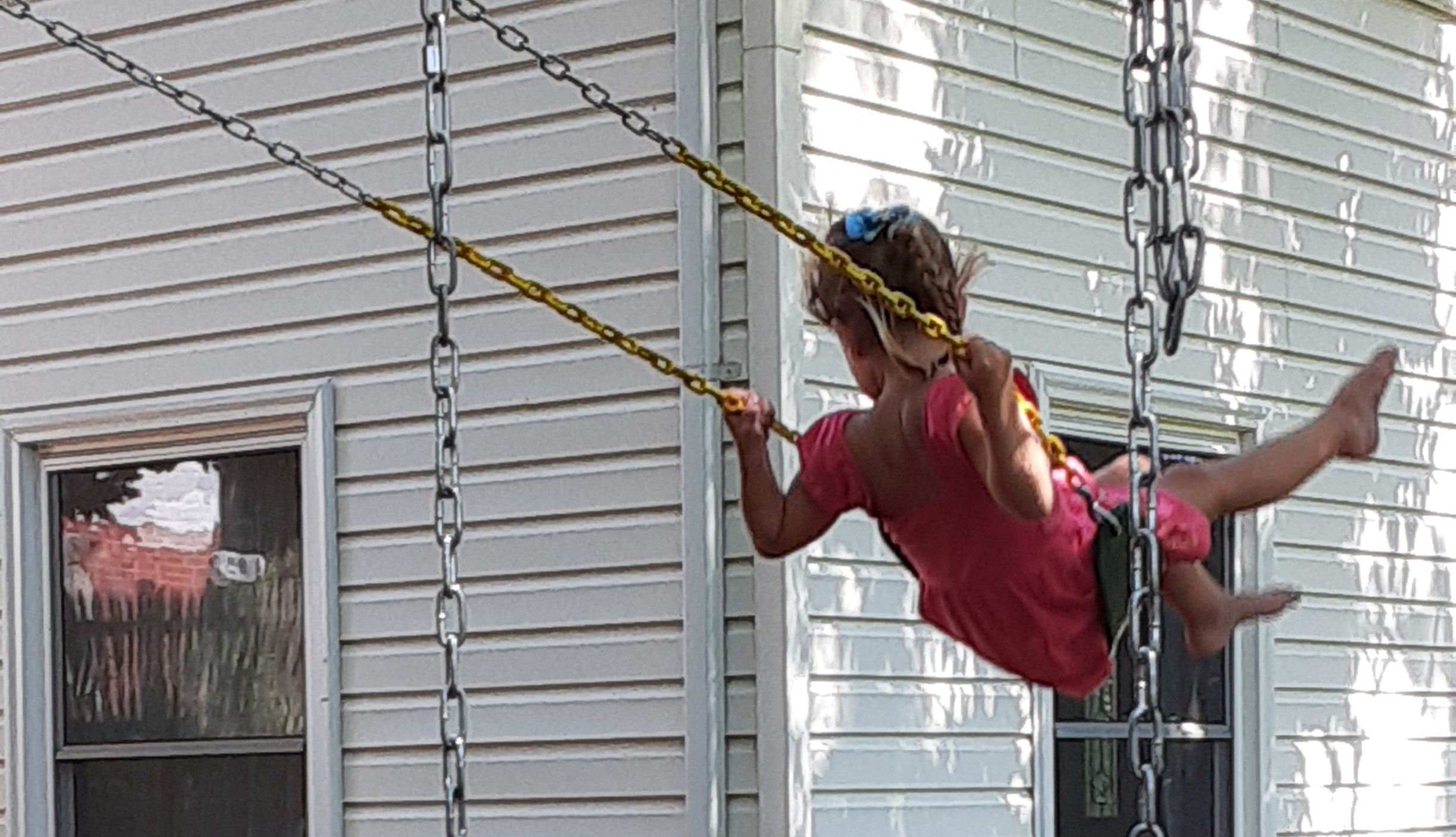

In life in general, including one’s writing life, the remaining-at-rest side of inertia is typically a hurdle to overcome. In its simplest form, the longer one goes without writing (or scheduling a doctor’s appointment, sending condolences, making an apology, weeding the garden, etc.) the more effort it takes to make it happen.

Despite all the anatomical evidence available, crash test dummies used in car safety tests are modeled on an average male body from 1976. That might be why female drivers are 73% more likely to be seriously or fatally injured in a car accident.

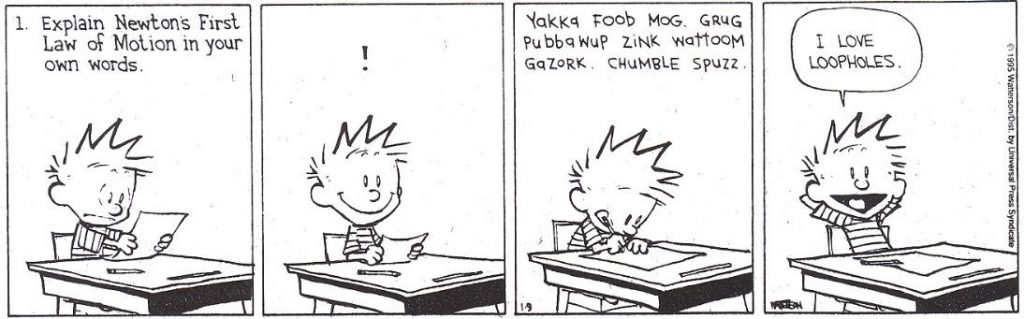

Procrastination is a bear of not getting off the mark. Researchers suggest that it takes approximately 18 to 250 days to train yourself to a new habit. The first 21 days are said to be the most difficult, especially for a physical habit (regular exercise, quitting smoking, etc.).

This holds true for habits of thought, too. It’s a little more difficult to get precise numbers in this area, but studies show that you can train yourself to meditate, think positively, stop apologizing to everyone, even improve your memory. The brain, like the body, wants to remain at rest.

For humans, the continuing movement side of inertia, it seems to me, is both rarer and more beneficial. I think of it as being on a roll.

If you are on a roll, you may be having a run of good luck. (This expression, which alludes to success rolling dice, dates from the second half of the 1900s.) Enjoy it while it lasts, but the nature of luck is that it’s beyond one’s control.

Alternatively, being on a roll can mean enjoying a success that seems likely to continue. Continuing in the same habits will likely lead to a series of successes. This is true of everything from an athletic success to the first book in a popular series.

Being on a roll also means a period of intense activity. This building momentum side of inertia comes to the fore when meeting deadlines, whether work or social (like Halloween preparations).

The outside force part of the physicist’s law of inertia is where a writer’s free will comes into play. There are all sorts of things you can do to overcome inertia in your life. Identify and remove triggers for a behavior you want to change. Set reminders on a timer or a note taped to your wall.

Those outside forces can be the basis for a character’s motivation in your writing as well. Perhaps an overheard comment sparks a character’s curiosity to begin a massive research survey. Perhaps a health scare inspires a character to change jobs and move to the opposite side of the globe. Perhaps new of impending alien invasion encourages an entire planet to move all habitations below ground.

BOTTOM LINE: If you understand both sides of inertia, you can make it work for you!

In honor of International Women’s Day (March 8th), check for biases in your life, in your thought patterns, even in your writing. At its core, bias is often just mental inertia.