Today’s guest blog was written by Kathleen Corcoran

As discussed in last week’s blog, tea has played a vital role in military pursuits all around the world. However, tea has been a part of human culture far beyond warfare in every part of the globe since Chinese Emperor Shen Nong first drank it in 2737 BCE.

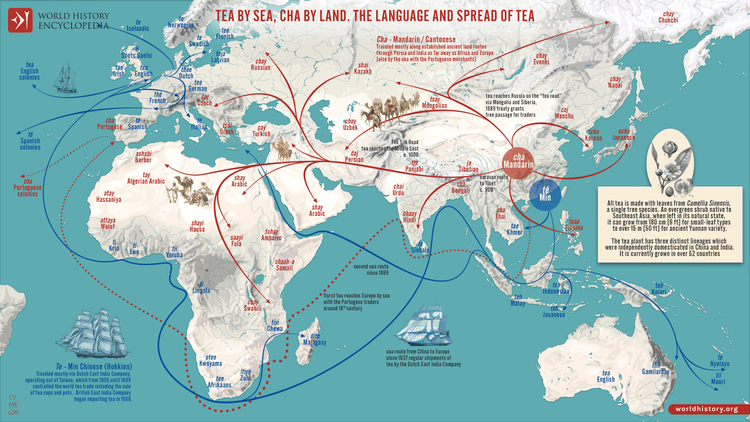

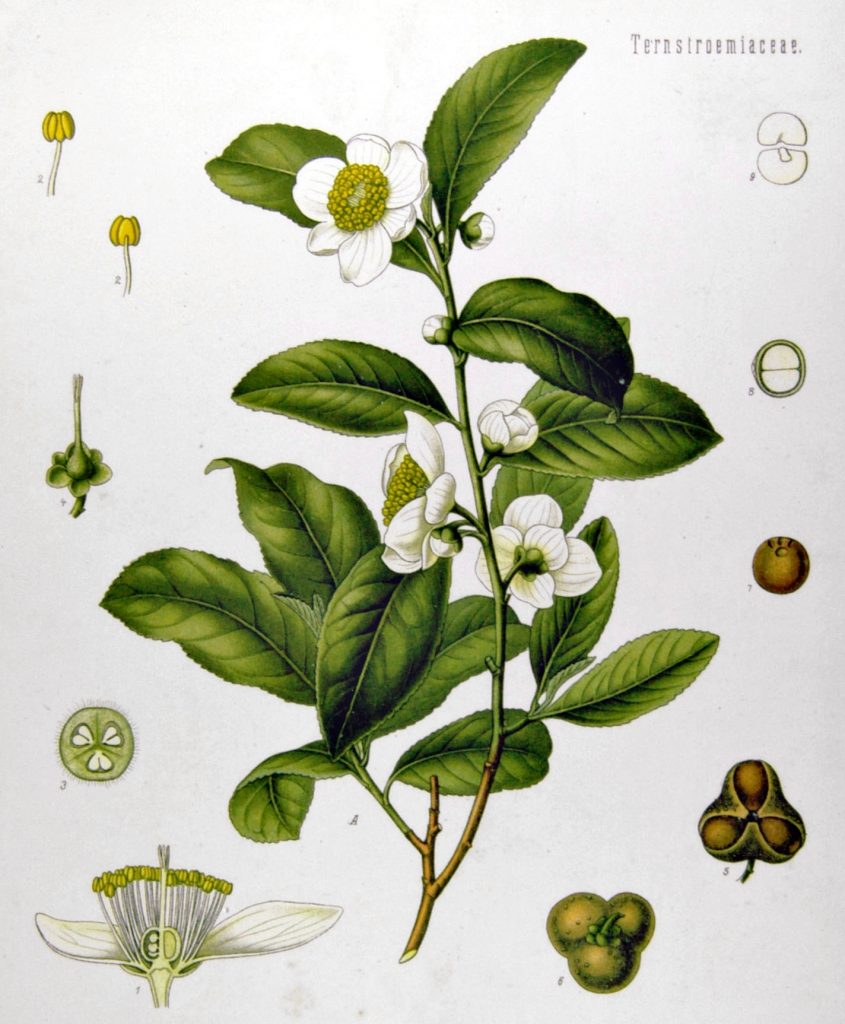

Camellia sinensis is a hardy bush, able to grow in a variety of climates. However, it requires a very specific micro-climate to develop leaves capable of making a tasty tea brew. Even so, international trade has allowed tea to grow in popularity all around the world.

Strictly speaking, “tea” (荼) refers only to the brew created from the leaves of the Camellia sinensis plant. Anything else is technically a tisane (from the Greek ptisanē “crushed barley”) or herbal brew. On the other hand, popular culture tends to refer to any drink made from brewed leaves as tea, so I will include other herbal drinks here.

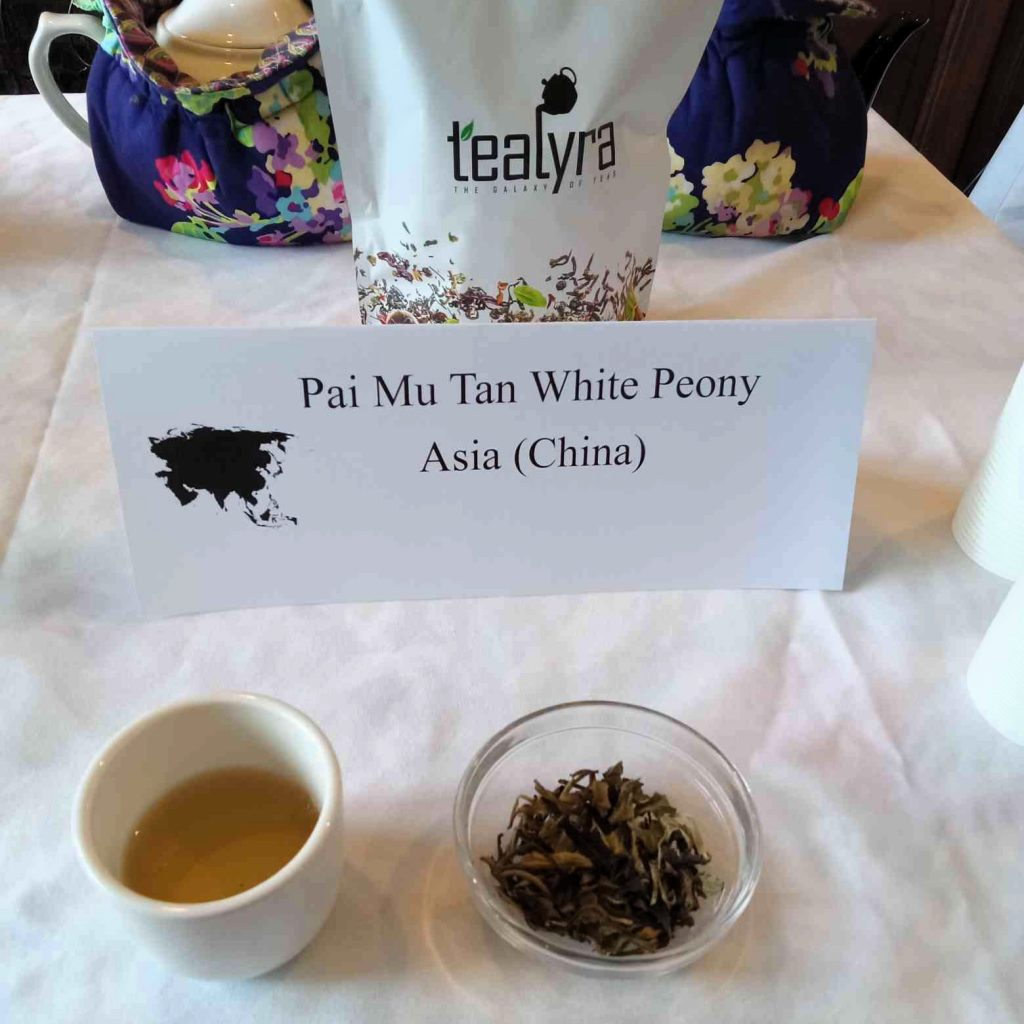

I had the pleasure of attending a lecture and tea tasting at Historic Green Springs recently. Historian Debbie Waugh presented an example tea blend from each continent and spoke about the history of each.

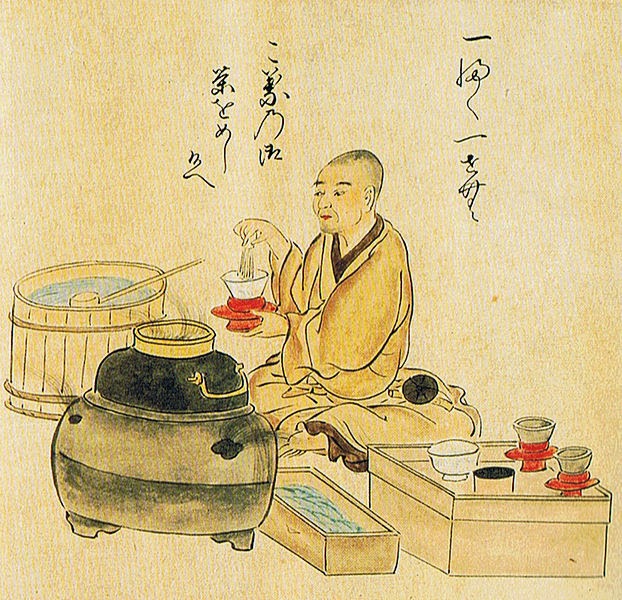

Asian Tea

Since its origins in southern China, tea production and consumption have played an important role there. China still leads the world in tea production, growing 14,542,600 tons in 2025. In addition to being a popular beverage, tea serves an important role in traditional Chinese medicine and cooking. Children serve tea to their elders to apologize for misbehaving. The tea house is traditionally a place where people can set aside social rank to have frank discussions. Doctors in China have been prescribing tea to patients since at least the Three Kingdoms period, 1800 years ago.

India holds the title of the world’s second largest producer of tea, and many of the most recognizable varieties originate there. Since before recorded history, the Singpho and Kamit peoples in northeastern India have been drinking “soma,” which may have been Camellia sinensis tea. Ayurvedic medical practice also includes many herbal teas. In addition to milk-brewed chai, many people in India drink basil, cardamom, and pepper teas.

The Silk Road brought tea from China through the Middle East centuries ago. In many Middle Eastern countries today, people serve sweet, hot tea to guests and business partners to signify hospitality. In fact, rejecting an offered cup of tea may be a sign of extreme rudeness.

White tea is made by plucking the unopened buds at the tip of a tea plant and subjecting them to minimal processing. Debbie Waugh selected this white Chinese tea from Tealyra. While brewing, the buds open like a blooming chrysanthemum flower, giving the tea its name.

European Tea

Though very few places in Europe have the ideal climate to grow tea, that hasn’t stopped people from shipping tea around the world to enjoy a cup or two. Or ten. Per capita, three of the world’s highest tea consuming countries are in Europe (Türkiye, Ireland, and the United Kingdom).

Each Turkish person consumes, on average, nearly 7 pounds of black tea (çay) every year! They grow much of it themselves, in the mild climate along the Black Sea. In neighboring Georgia, though no longer providing the entire Soviet Union with black tea from the Guria and Adjara regions, sixty one local tea producers still cultivate Camellia sinensis in the Caucasus mountains.

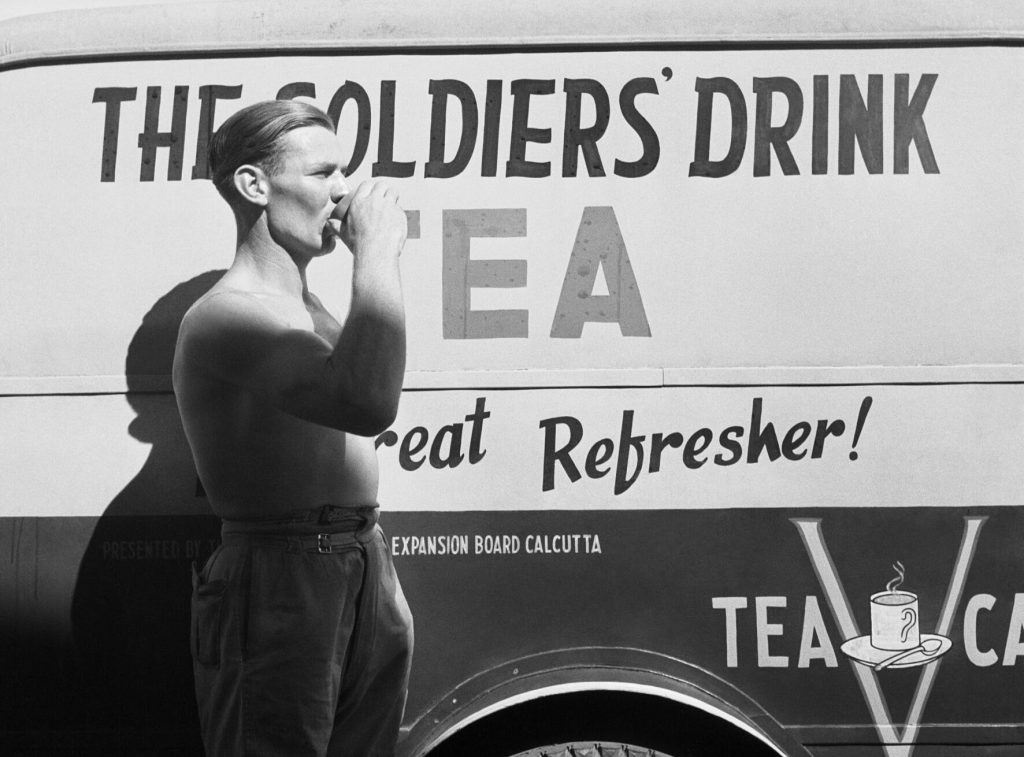

In Ireland and the United Kingdom (second and fourth in the world in tea consumption), tea plays a huge social role. Since tea first arrived in the 17th century, people have relied on tea to provide hospitality, celebrate, mourn, relax, socialize, or simply nourish their bodies.

Many other countries in Europe grow the herbs and spices to make distinct tea blends. Bergamot oranges, which produce the oil that gives Earl Grey tea its distinctive flavor, originate in Italy.

Debbie Waugh selected this Earl Grey tea to represent Europe. From Fragrant Tales, it combines Ceylon black tea with Italian bergamot oil.

African Tea

In 2025, Kenya was the third most prolific producer of tea in the world. In addition to popular black teas, Kenyan tea growers cultivate purple varieties of Camellia sinensis tea. Uganda, Malawi, and Tanzania all have ideal climates for growing tea and export significant quantities. In Rwanda, tea has become both an export commodity and a tourist attraction. Visitors to Rwandan tea plantations can combine tours of tea fields with wildlife safaris.

However, most of the Camellia sinensis tea produced in Africa is destined for export. A variety of herbal blends are far more popular for local consumption.

South Africa’s Aspalathus linearis bush produces rooibos (also called red or bush tea), a caffeine-free tisane. Ntingwe, also from South Africa, is a blend of rooibos, Honeybush, and other herbs. In northern Africa, people make very popular teas from mint leaves or hibiscus flowers. During Ramadan, many Muslims in west Africa make kinkeliba from the leaves of the Combretum micranthum bush.

This Rooibos from The Tea Smith comes from South Africa. As Debbie Waugh pointed out, rooibos has loads of antioxidant benefits.

Oceanian Tea

Though Fiji grows black tea for export, most Fijians prefer to make kava from the local yagona root.

Long before the British arrived Down Under, Aboriginal Australians were brewing infusions of the Mānuka (Leptospermum scoparium) tree. Captain Cook called the Mānuka a “tea tree” because of the brew’s similarity to tea.

When the first British colonists (and convicts) arrived in Australia in 1788, they brought tea with them. Wealthy British immigrants continued their customs of high tea on fancy china. Out in the bush, people brewed tea in billy cans over open fires.

In northern Queensland, where the climate is closest to that of southern China, the Cutten brothers established a tea plantation in 1884. However, the majority of tea in Australia is still imported. Prior to 1950, Australia held the title of highest per capita tea consumption in the world.

New Zealand has had a similar history of tea consumption. At the beginning of the 20th century, New Zealanders drank more tea, per capita, than the British!

Australia has a large market for herbal tisanes, producing them for both domestic use and export. Debbie Waugh presented this lemon myrtle blend from Full Leaf Tea Company.

North American Tea

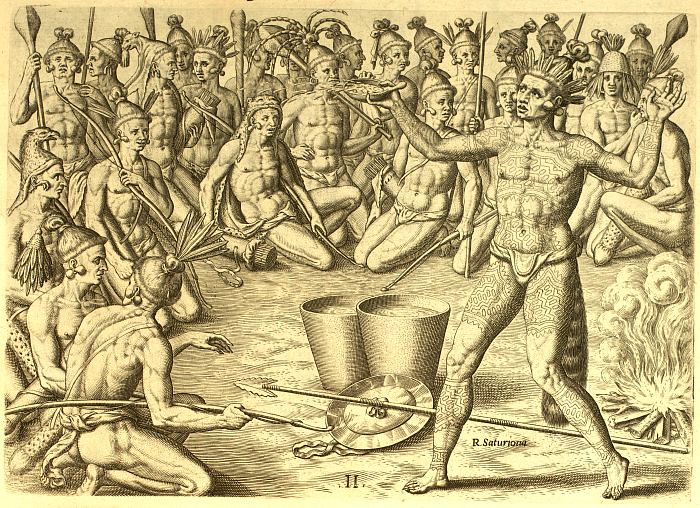

Long before European colonists arrived, people in North America drank many herbal brews, particularly yaupon. By roasting and boiling the leaves of the yaupon holly tree (Ilex vomitoria), people created the mildly caffeinated “Beloved Drink” for ceremonial, social, and everyday use. Historical and archaeological records show that yaupon’s popularity stretched from the Algonquin on the East Coast to the Tankowa along the Rio Grande.

Although Mexico produces two thousand tons of black tea yearly, few Mexicans drink tea regularly. Instead, people drink a variety of herbal teas, such as agua de Jamaica (hibiscus tea). In cold weather, many Mexicans drink champurrado, made from chocolate, corn masa, and spices.

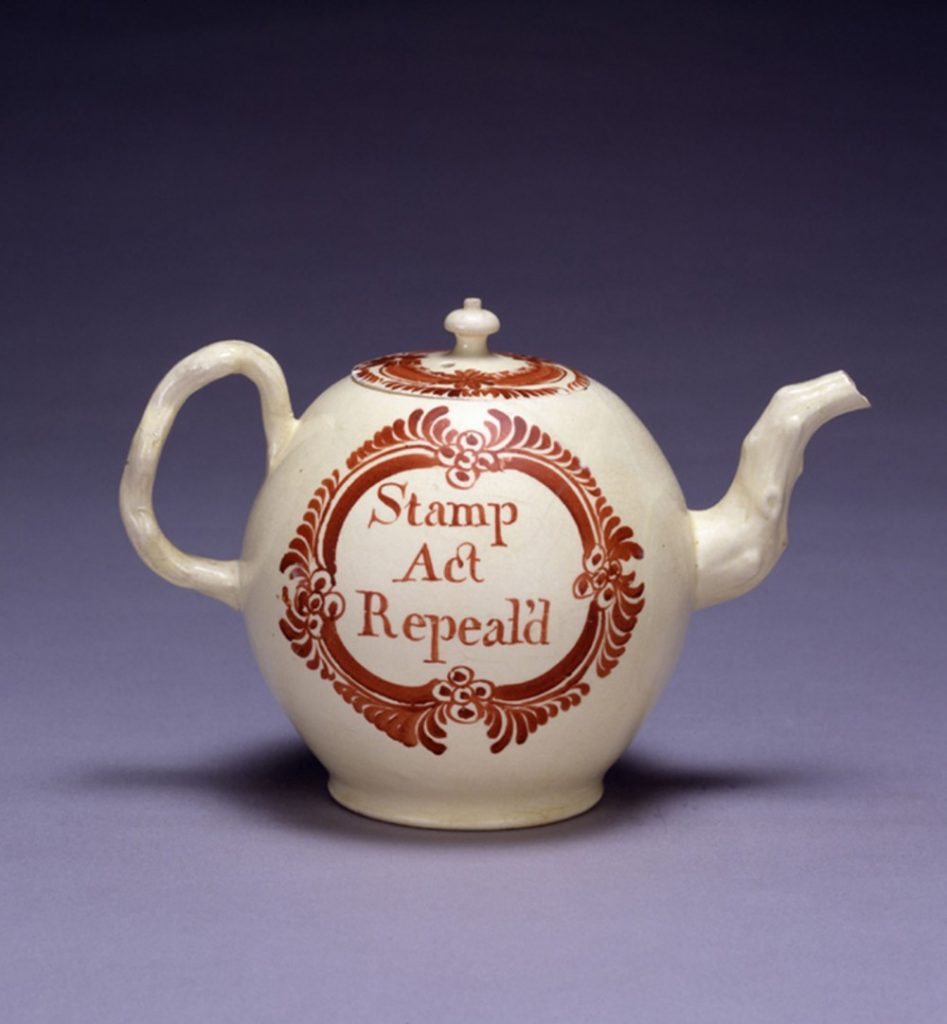

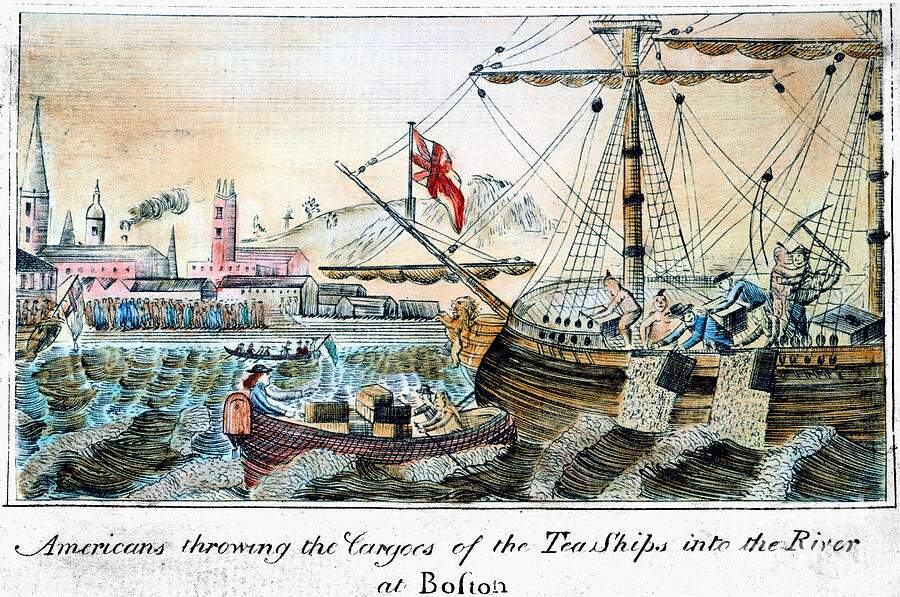

The Dutch East India Company may have been the first to import Camellia sinensis tea to North America in 1647. Colonists in Salem served boiled tea leaves with butter as a vegetable dish. The politics and economics of tea imports played a major role in the American Revolution. Canadian Theodore Harding Estabrook first developed the method of pre-blending tea to facilitate shipping.

People have been trying to grow Camellia sinensis in North America since 1744. However, it wasn’t until 1772 that colonists in Georgia were able to grow tea plants successfully. Few places in North America have the correct microclimate for tea, but there are plantations in Louisiana, Oregon, Alabama, South Carolina, and Washington State.

Charleston Tea Garden, in South Carolina, is the only large-scale tea plantation in America. Debbie Waugh selected this blend of green tea with mint, all grown and blended domestically.

South American Tea

In South America, yerba mate (Ilex paraguariensis) is far more popular than Camellia sinensis for making a cup of tea. Traditionally, yerba mate is made by pouring hot (not boiling!) water over mate leaves in a hollowed gourd and drinking the resulting brew through a sieved straw. The name comes from the Spanish word for “herb” (yerba) and the Quechua word for the hollow calabash gourd (mati).

According to historian Debbie Waugh, yerba mate has “the strength of coffee, the health benefits of tea, and the euphoria of chocolate.”

Uruguayans drink more yerba mate than anyone in the world. In Paraguay, people drink a chilled version of yerba mate they call tereré. Brazilians enjoy erva mate on the go or as part of communal mate ceremonies. Argentinian gauchos drink yerba mate for health benefits while on long cattle drives.

Portuguese colonists established black tea plantations in the Brazilian highlands in 1812, but those mostly collapsed with the abolition of slavery in 1888. The Argentinian government has invested heavily in tea cultivation and is currently the ninth most prolific tea producer in the world. Tea gained popularity in Chile after the British navy assisted Chileans in their war of independence from Spain.

Yerba Mate can be dried over a fire, giving it a smoky flavor. Debbie Waugh provided this unsmoked yerba mate from EcoTeas Organic Yerba Mate.

Antarctic Tea

Sadly, my visions of vast greenhouses growing tea at the South Pole were not accurate. Still, there is a history of tea in Antarctica.

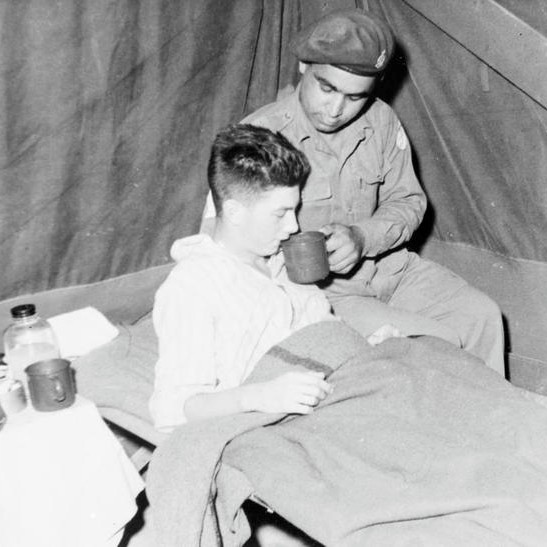

When Robert Scott outfitted his expedition to reach the South Pole, every member packed 16g of an especially strong black tea per day. He wrote, “…admitting all that can be said concerning stimulation and reaction, I am inclined to see much in favour of tea. Why should not one be mildly stimulated during the marching hours?”

Years after Scott’s team perished on their return journey, Ernest Shackleton retrieved an unopened tin of tea from Robert Scott’s Antarctic campsite. Scott’s Hut still stands in Antarctica, holding some of the supplies they packed for their journey.

Among the contents of the Scott expedition hut are tins of the special tea blend Typhoo created for the explorers. In 2012, Typhoo Tea sold a recreation of that blend to raise money for preserving the hut. Debbie Waugh presented a similar black blend from Typhoo Tea, reminiscent of what early Antarctic explorers drank.