One is the temptation to “make it real” by including (boring and unnecessary) details about a route driven. Does anyone really care that your character took Three Chopt to Gaskins and merged onto I-64 west, exited onto I-295 to pick up I-95? Ditto with such details as taking Horsepen to Boulevard, taking a right onto Malvern, and a left on Cary St. Local readers might think, “Yeah, s/he knows the territory.” But if these specific turns and streets aren’t central to the plot, find a more dynamic way to establish your credibility!

If your plot involves any sort of violent crime, whether you’re a mystery/crime writer or not, you should know forensic nursing. In broad terms, forensic nursing is where the healthcare system and the legal system intersect.

Photo credit: KOMUnews via Visual Hunt / CC BY

Photo credit: KOMUnews via Visual Hunt / CC BY

Survivors of violent crimes typically come through the ER, where their medical needs are taken care of—setting broken bones, stitching wounds, etc. Ideally, the patient spends as little time as possible in the controlled chaos and tension of the ER; the goal is no more than 45 minutes.

Then they are escorted to a quiet, comfortable room furnished much like a small living room, but with drinks and snacks as well as TV. Anyone accompanying the patient would typically wait here during the examination. The area is secured, and only people the patient chooses to bring are allowed into the room. These people might be family or, perhaps, a trained volunteer from an organization such as Hanover Safe Place, which supports survivors through what is inevitably a traumatic time at the hospital.

The patient then meets with a forensic nurse. The forensic nurse’s role is to record the details of the crime and collect physical evidence. This process typically takes 3 to 4 hours.

Background information comes first, including general medical history as well as questions about any injuries, surgeries, diagnostic procedures, or medical treatments that might affect the physical finding. But then come pages of more detailed and focused questions. For example, in cases of sexual assault, not only question about the assault itself and perpetrator(s) but also about the date, time, type, partner’s race, and relationship of last consensual intercourse; and since the assault, whether the patient bathed or showered, douched, brushed teeth, defecated, urinated, vomited, wiped or washed affected area, changed clothes, or had consensual intercourse.

For strangulation cases, they ask how the patient was strangled—one-handed, two-handed, knee, forearm, ligature—how long it lasted, and whether there was more than one incident.

A danger assessment is conducted as well, focusing on whether the violence is escalating in severity or frequency, whether weapons (especially guns) are available and/or used, drug or alcohol use, presence of children, and control of the survivor’s daily activities and social interactions.

Although the verbal data are crucial, the physical exam is central to forensic nursing. Samples of blood, urine, hair, and swabs of orifices are taken. Specialized equipment is available. Photographs are taken. Hair is combed, nails cleaned and clipped. The patient stands on a plastic sheet to remove clothing, to catch any random debris.

Chain of custody must be carefully controlled and documented.

Children have special treatment as well. They are given a toy that they can keep. They’re also given tablets and pencils or markers to draw pictures that can help in understanding the assault. Sometimes an outline of a person is presented for the child to mark where he or she was touched or hurt.

Improvements and refinements are always in progress. Once upon a time, a survivor might be asked to detail the crime by a dozen different people. Now recounting the crime waits for the forensic nurse, diminishing the impact of reliving it.

When a patient’s clothes are taken in evidence, they are given generic going-home clothes. These are grey sweatpants, t-shirt, and—until recently—the granny panties pictured above, one size for all. A college student survivor said that having to wear those granny panties made her feel violated all over again.

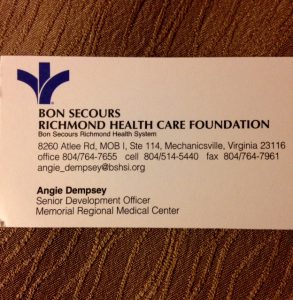

She organized her sorority sisters to provide hundreds of pairs of new panties in varied colors, styles, and sizes. All of the clothing provided to survivors is donated. Should you or your group want to donate new clothes, new toys, child pillowcases, gas cards, food cards—or money!—here’s your contact. And, by the way, she gives talks about the program.

Forensic nursing is a relatively new medical specialty. In 1992, 72 registered nurses—mostly sexual assault nurse examiners—came together to form the International Association of Forensic Nurses. Since 1993, Bon Secours Forensic Nursing in Richmond has served survivors of sexual assault, child sexual abuse, and domestic violence. Now a team of 10 full-time nurses work with 26 agencies to serve survivors of any type of violent crime.

Bon Secours is atypical. There are over 300 hospitals in Virginia, and many of them have no full-time forensic nurses. Therefore, patients from all over central Virginia can end up at Bon Secours. They assist more than 2,200 patients per year.

Bon Secours is a premier forensic nursing program. For the sake of your story line, you might create more conflict in the story if the characters botch the process. A screw-up could taint evidence or miss it. Insensitive treatment could leave the survivor among the walking wounded.

Last but not least, put this worthwhile event on your calendar!

Benefiting Bon Secours Forensic Nursing

Sunday, October 30, 2016

2:00-5:30 p.m. at Hilton Richmond

Hotel & Spa

Short Pump

Genetic mosaics are not so rare, formed by fusing two gametes in utero or a placenta shared between fraternal twins or by the mother’s cells crossing the placental barrier and continuing in her child. Imagine that a woman had children with all of her genetics, so the cell lines were thoroughly mixed.

Fantasy, on the other hand, is making it up out of whole cloth. Even so, it could draw on science for an idea. For example, another book I came across recently has such possibilities: TEMPERATURE-DEPENDENT SEX DETERMINATION IN VERTEBRATES edited by N. Valenzueta & B. Lance. It contains articles by leading scholars in the field and reveals how the sex of reptiles and many fish is determined not by the chromosomes they inherit but by the temperature at which incubation takes place. Fantasy would be a story in which human sex is determined by ambient temperature. And perhaps it can vary as the temperature varies. And so forth.

Names have long fascinated me. You may recall that I wrote an earlier blog on naming characters. But as a writer, you will be naming much more, for example, towns, streets, roads, rivers, mountains, events, buildings. When I last lived in Ohio, I lived in Portage County. The county was named for the portage between the Cuyahoga and Tuscarawas Rivers. Cuyahoga is an English transliteration of its Mohawk name. The Tuscarawas River has had several names—Little Muskingum River, Mashongam River, Tuscarawa River, and Tuskarawas Creek, all derived from Native American terms. Ohio’s Native American roots are clearly visible, reflected in the names of counties (including Ashtabula, Coshocton, Geauga, Hocking, Huron, Logan, Ottawa, Sandusky, Scioto, Seneca, Wyandot) as well as rivers and cities of the same names. The state of Ohio takes its name from the Ohio River—which is from the Iroquois word meaning great river or large creek.

I now live near Three Chopt Road. In colonial times, it was called Three Notch’d Road, a major east-west route across central Virginia. Historical consensus is that it was originally an Indian trail, marked by three notches cut into trees.

The trail extended hundreds of miles, from the fall line of the James River (now Richmond, VA) to the Shenandoah Valley, crossing the Blue Ridge Mountains at Jarmans Gap. Today a large part of U.S.Route 250 in Virginia as well as much of Interstate 64 follow that historic trail. You can look up Jack Jouett’s Ride or the activities of Marquis de Lafayette for the role of Three Notch’d Road in the Revolutionary War.

![By Glass Negatives of Indians (Collected by the Bureau of American Ethnology) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons Portrait of Marcia Pascal, daughter of Col. Pascal.](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/0/00/Portrait_of_Marcia_Pascal%2C_daughter_of_Col._Pascal.jpg)

Perhaps the reason I tend to notice Native American connections is that I have Cherokee blood on my father’s side. But the richness of place can be shaped by any ethnic heritage. Think Amish, Pennsylvania Dutch, African or Chinese American, for example.

Think of “place” in both the broadest and narrowest terms—as Garrison Keillor does for Lake Woebegon, i.e. whether your place is your character’s apartment or a country, go beyond geographic labels as found on maps to show that you really know the place.

In your daily to-and-fro, pay attention to places and the elements that make them distinctive from and/or similar to other places. If you are writing about a real place, get into it a bit—the history, feel and tone of it, whatever helps identify it. You should know a lot about your place that never makes it into your work. If you’re making it up, you must know it just as well to make it feel richly real.

Sometimes a detail can tell a lot about your place. When I was writing Nettie’s Books, I collected vivid names for places, roads, and churches. Not all of them ended up in the book, but I still like the flavor of Old Footpath Road, Horsehead Lane, Folly Road, Whispering Forest, Church of God-the Prophecy, Tockwough, Buzzard’s Bottom, Integrity Drive, Broken Bit Lane, Wild Sally Road, Hell Neck Road, Church of the Risen Lord, Walkabout Mountain Lane, Slaughter Pen Hollow, Sunnyside Church of the Brethren, Fresh Fire Church of God, Message of Freedom Church, Turning Point Church, Willing Hill, Puddin Ridge Road, Paradise Found—to give a few examples.

I often walk in Deep Run Park, which was looking pretty good the last time I was there. Lo and behold, trails are still marked on trees and roots, although now with paint rather than notches.

If I ever write a body into Deep Run Park, I’ll have the details to make it real!

Don’t put your poetry or prose on a diet; go for richness in every morsel.