“Self-soothing” refers to behaviors people use to regulate their emotional state by themselves. It’s a strategy used to regain equilibrium after an upsetting event, or when facing a stressful situation. (For example, when a child’s parents argue, or an older person has to make a public presentation.)

Self-soothing behaviors are often apparent early in life, and are calming or comforting for a child or adolescent. Infants, for example, may be seen repeatedly sucking fingers or thumbs, hugging a toy or blanket. These habits may continue for years.

Self-soothing behaviors are repetitive/habitual in nature—and are often not consciously applied. Do you touch your hair, twist a ring, straighten your tie, etc.? Noticing when you engage in such behaviors can help you recognize mildly tense or stressful situations. It’s another form of self-awareness.

Following a shock, a traumatic or upsetting event, all people need soothing. In these more intense situations, two common self-soothing behaviors include reaching for an alcoholic drink or a tub of ice cream or other emotional eating. However—as you no doubt know—these kinds of self-soothing behaviors can cause additional problems.

Several self-soothing behaviors can lead to other problems: binge-watching TV, compulsive gaming, or internet surfing. Many superheroes have unhealthy self-soothing behaviors, including Jessica Jones and Iron Man.

Constructive Methods of Self-Soothing

Positive Psychology published an article suggesting several more positive strategies: “24 Best Self-Soothing Techniques and Strategies for Adults.” The following 7 suggestions quoted below are included in that article.

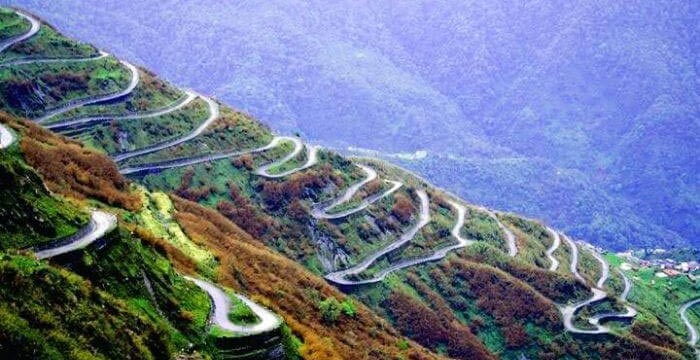

1. Change the Environment

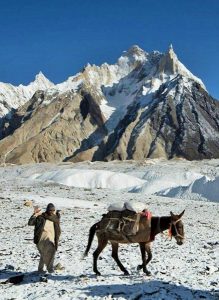

If possible, just change the environment for a few minutes. Go outside and focus on greenery or find a soothing indoor space with a pleasant view or ambiance.

(The origin of the “Green Room” in theaters may stem from Elizabethan actors resting “on the green” between scenes to calm their eyes and their nerves. As the wavelength of green light causes the least strain on the human eye, those Elizabethans may have been on to something!)

2. Stretch for Five Minutes to Move Any Blocked Energy

Often, after upsetting news or a shock, our bodies respond by freezing and energy gets blocked. A few simple trunk twists, neck rotations, or bends at the hip to touch the toes can help shift stagnant energy.

(Even without a shock, our bodies tend to store tension and stress in our backs, shoulders, and necks. Stretching these areas can prevent headaches and improve circulation.)

3. Take a Warm Shower or Bath

Treat yourself with soothing body wash or bubbles and a fresh, soft towel afterward.

(For best results, do not use overly hot water and avoid scrubbing too hard. If hot water is not available, you can turn to oil, smoke, some types of mud, or simple cold water to achieve cleanliness and promote peace of mind.)

4. Soothing Imagery

Find soothing things to look at such as a burning candle, soft lights, pictures of loved ones, favorite places, or perhaps some framed inspirational resilience quotes or affirmations.

(The color green is most restful to the human eye, but some evidence suggests that other colors may have a calming effect on stress and mood. According to the principles of chromotherapy, surrounding oneself with blue, purple, or white can calm, soothe, and relax the central nervous system.)

5. Soothing Music

Listen to favorite tracks that have a calming effect or one of the many relaxing music videos for stress relief that are available online.

(Harp music in particular has a soothing effect on the body as well as the mind. Research has shown that listening to harp music improves pain management, blood pressure, and heart rate regularity.)

6. Soothing Smells

Create pleasant smells by using an essential oil diffuser, scented candle, or incense. Also, try using scented hand lotion.

7. Self-Compassion

Speak compassionately to yourself aloud. Talk to yourself like a good friend would. Give yourself the grace to be off-balance and the space to just be as you are for a while.

Soothing Every Sense

When people experience high levels of stress or discomfort often, some therapists recommend making a self-soothing box that includes objects or reminders of how to soothe all five senses:

- Comforting smells such as scented candles, essential oils, or body lotion

- Pleasant tastes such as herbal teas or favorite snacks

- Soothing things to touch such as a favorite sweater, wrap, or stress ball

- Comforting sights such as photos of loved ones, pets, or favorite places

- Soothing sounds such as a favorite piece of music or guided meditation track

Most of us are familiar with people soothing other people—a hug, a back-rub, a shoulder to cry on. During COVID, when interpersonal soothing was less available, researchers studied the benefits of self-touching (Dreisoerner et al., 2021). They found that both self-soothing touch (in this study, most participants chose to place their right hand on their heart and their left on their abdomen while focusing on the rising and falling of their breath) and receiving a hug from another person were equally effective at lowering stress levels.

When adults are distressed, it’s difficult to regulate potentially disruptive emotions like anger, fear, and sadness, especially in a public space such as the workplace. If you want to explore self-soothing further, just look online. You will find lists of techniques from 8 to 100. Surely there’s something there for everyone.

Bottom Line: Everyone experiences distress of various sorts and at various levels. Self-soothing is a life skill worth learning.