Yesterday, November 5, I met with Spotlight, the Colonial Heights High School club which focuses on literary and fine arts. I talked with these young, creative teens about fiction in general and historical fiction in particular.

Stating the obvious: in historical fiction, the plot takes place in a setting located in the past. What may not be so readily obvious is that beyond that, anything goes! Although this umbrella covers theater, opera, cinema, TV, etc., and my comments likely apply there as well, my focus has always been on the traditional: historical novels and short stories.

Historical fiction can be any genre and format. Romance, action/adventure, mystery, children’s literature, young adult novels, sci-fi, literary fiction, fairy tales, fables, satire, comedy, horror, even epic poetry—anything you can come up with is fair game. And it can be any length, from flash fiction to multiple-volume series.

The foundation of historical fiction is good writing. Therefore, start by mastering the craft. Ursula Le Guin’s book Steering the Craft is short, readable, and excellent instruction (although my personal opinion is that the sailing metaphor gets a bit trying by the end). But beyond that, consider what will give your writing authority and make it believable. So, here, in no particular order, are sample questions you would do well to answer.

What did people eat? People must eat. Beyond that, nothing is static. Food fashions change. The availability of various foods changes. Cooking methods and utensils change, how tables are set and what constitutes good table manners change. Even the timing of meals change—such as when the main meal of the day was eaten. And what was eaten: one example, a full breakfast is a staple of British cuisine, and typically consists of bacon, sausages and eggs, often served with a variety of side dishes and a drink such as coffee or tea. Prior to 1600, breakfast in Great Britain typically included bread, cold meat or fish, and ale. On an American farm table, pie for breakfast was common. You can search history of breakfast online and retrieve lots of valuable information by period of history and country.

How did people talk? The basic here is vocabulary, the words for ordinary objects and actions. Then, too, a word may not mean the same thing it once did. “Compromise” had a very different meaning for a couple in Jane Austen’s time compared to opponents in a political intrigue set in 1990. But phrasing comes into it, too: at some point, people became less likely to say “pardon me” and more likely to say “excuse me.” Besides the historical period, consider language specific to action; for example, carnival workers or mobsters.

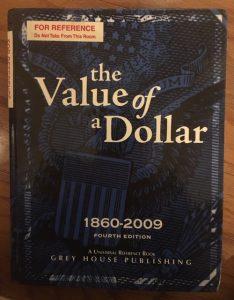

What did things cost? Everyone knows prices change. The basic point here is how much things cost during your time period. And perhaps even more interesting, what was bought? For example, in 1905 a household was likely to buy stove polish (at twenty-five cents a can). Or during the Great Depression in the United States, a man might berate his wife for “driving all over the county, like gas doesn’t cost ten cents a gallon.” Inserting a few such details gives a story authority as well as richness—assuming you get it right. The latest edition of this book (the 5th) is available from Amazon, $155 new and $25 used. For your purposes, new probably isn’t necessary, and library discards come available for a dollar or two.

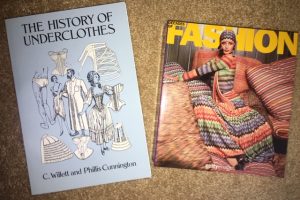

What did people wear? For example, did women wear underpants? Had bras been invented? Were corsets still in use? And related questions having to do with where the clothing came from, how much of it a person was likely to have, and how it varied by socioeconomic status.

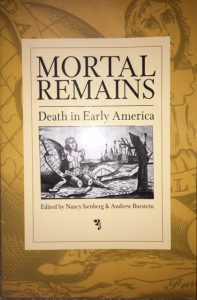

What was involved in birth, death, and marriage? Most historical fiction will touch on one or more of these nearly universal events. Where did births take place and who attended? What about funerary practices? Would bodies be embalmed, burned, put on a scaffold for birds of prey to clean the bones? For marriage, consider age, who consents, what the ceremony likely entailed. For women, what rights did she lose and/or acquire with marriage?

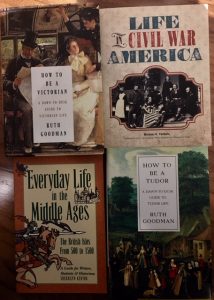

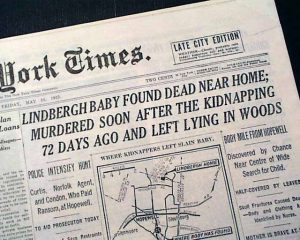

What was happening in the world at the time? Some awareness or mention of major events is unavoidable. For example, if your story is set in 1863, the American Civil War was a relevant event whether or not it was the focus of your plot, and even if your story is set in London or Paris. The kidnapping of the Lindbergh baby and finding the body in 1932 was similarly followed worldwide. For an excellent one-volume history of the United States, try Jill Lepore’s These Truths.

Doing your research. The above questions are just examples of things you need to know to make your historical work of fiction live for the reader. The list is endless: recreation and entertainment, mode of transportation and the time it took to get from place to place, weapons, toys, houses or whatever dwellings, how tall people were, hair styles. . . If you know the question you want to ask, online searching is convenient and inexpensive. Personally, any information I’m likely to want to refer to repeatedly, I like to have in physical books. Reading about the time of your plot is extremely valuable. And I find it fascinating. I have many books like the ones pictured above to get an overview of life during the period of interest, presenting answers to most of your factual questions in one convenient package.

Last but not least, read books written during and set in the time you’re writing about. Read extensively—meaning both a lot and broadly. It will give you a feel for tone, pacing, and (probably) things to avoid in your own writing!

BOTTOM LINE: Besides the foundation of good writing, historical fiction is built on research. Enjoy!