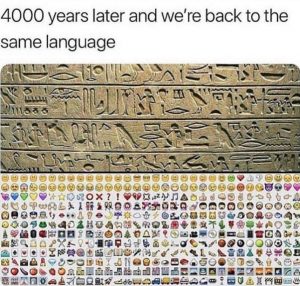

I approached this blog with the opinion that relying on emoticons—i.e., emojis—is dulling out ability to express emotions with rich language and subtlety. How can one retain, let alone develop, verbal and written skill if it isn’t practiced? The above image seemed to confirm my opinion: if hieroglyphics were sufficient for purposes of communication, why did other forms develop?

I searched online and did find some support for my original opinion. One study by YouTube (a survey of 2000, ages 16-65) found that 94% believe there has been a decline in the correct use of English, 80% of those saying youngsters are the worse culprits. Over a third of British adults believe that emojis are responsible for the deterioration of the English language—less command of spelling and grammar, due to use of spell check and predictive text. Although emojis convey a message, they breed laziness, diluting language expression. A common prejudice is that an emoji is the equivalent of a grunt, a step back in literacy, making us poorer communicators and maybe even dumber.

But all of this reflects what people think or feel. Where are the data? Academic research warns that peppering an email with emojis could harm your job prospects by making colleagues less likely to share information with you. Using emojis in the workplace doesn’t increase perceptions of warmth, it actually decreases perceptions of competence.

On the other hand, research commissioned by the dating site Match.com, released in 2017, a survey of 5600 singles found that the more emojis people used in their texts, the more dates—and sex—they have. The inference from this research was that using emojis made it easier for the potential match to gauge the message. Emoji users were concluded to be more effective communicators.

Originating on Japanese mobile phones in 1999, they’ve become increasingly popular worldwide since then. When Apple released a set of emojis in 2011, the uptake of emoji took off. Emojis to replicate non-verbal communication are used six billion times a day. Over time, the options to refine a particular emotional expression have increased.

When you look back over time, the power of image has always been there. Even prehistoric images such as cave paintings have been incredibly communicative: we can analyze those drawings and understand them thousands of years later. Pictures have the ability to transcend time and language—to be universal.

In the course of my reading, I found that Alexandre Loktiov, an expert on hieroglyphics and cuneiform legal texts, had this to say: “For me, they’re essentially hieroglyphs and so a perfectly legitimate extension of language. They’re signs which, without having a phonetic value of their own, can ‘color’ the meaning of the preceding word or phrase. In Egyptology, these are called ‘determinatives’—as they determine how written words should be understood. The concept has been around for 5,000 years, and it’s remarkably versatile because of its efficiency. You can cut down your character count if you supplement words with pictures—and that’s useful both to Twitter users today and to Ancient Egyptians laboriously carving signs into a rock stela.”

Emojis break down language barriers because people understand what the symbols mean, regardless of their native tongue. Perhaps its possible to learn a lot about a person from their preferred emojis. On the other hand, problems with emojis include cultural differences in the meaning of a given image. For example, two flagrant cases: apparently an eggplant has been taken up as a representative of a penis, a peach as a stand-in for a buttocks. One might inadvertently offend the recipient, even in more subtle ways. Public demand led to the option of modifying skin tone on the emoji.

In face-to-face interaction, up to 70% of emotional meaning is communicated via nonverbal cues. These include tone of voice, eye gaze, body language, gestures, and facial expression. Vyvyan Evans, an expert on language and digital communication, maintains that the emoji’s primary function is not to usurp language but to fill in the emotional cues otherwise missing from typed conversations.

He also had this to say: To assert that emojis will make us poorer communicators is like saying facial expressions make your emotions harder to read. The idea is nonsensical. It’s a false analogy to compare emojis to the language of Shakespeare—or even to language at all. Emojis don’t replace language: they provide the nonverbal cues, fit for the purpose in our digital textspeak, that helps us nuance and complement what we mean by our words.

One thing is sure: emojis are not only an integral part of e-communication. They are embedded in popular culture, and are making inroads in the general culture.

- Over 90% of the world’s 3.2 billion internet users regularly send “picture characters” (as the word means in Japanese) with over 5 billion being transmitted everyday on Facebook Messenger alone.

- The 2009 movie Moon features a robot who communicates in a neutral-tone synthesized voice plus a screen showing an emoji representing the corresponding emotional content.

- In 2014, the Library of Congress acquired an emoji version of Herman Melville’s Moby Dick.

- In 2015, Oxford Dictionaries named the Face with Tears of Joy emoji the Word of the Year.

- May 2016, Emojiland, a musical, premiered in Los Angeles.

- October 2016, the Museum of Modern Art acquired the original collection of emojis from 1999.

- November 2016, the first emoji convention, Emojicon, was held in San Francisco.

- In 2016, a High Court judge in England included a smiley face emoji in an official ruling, in an attempt to make the judgment in family court clear for the children it affected.

- March 2017, the first episode of Samurai Jack featured alien characters who communicate in emojis.

- April 2017, Doctor Who featured nanobots, called Emojibots, who communicate using emojis only.

- July 2017 Sony Pictures Animation released The Emoji Movie.

Alexandre Loktionov (mentioned above) said “. . .we have to think of the purpose of the means of communication, and in the case of emoji, we as a culture need to decide what they are: do we want them to be a bona fide script with full capability, or are they just a tool reserved for very specific purposes (alongside conventional means of writing)?”

In conversation with other writers, it seems we/they use emojis for specific purposes, limited entirely to electronic communications. For literary writing, they are irrelevant.

Some have asserted that the emoji is the fastest-growing language in history—for good or ill. How do you feel about emojis? If you use them, how?