For more than a month, people have been bombarded with ads, displays, and commercials about things to buy for Halloween: costumes, candy, house decorations, yard displays, etc., etc., etc. Indeed, more money is spent on Halloween than any other holiday except Christmas—which I find pretty horrifying in and of itself.

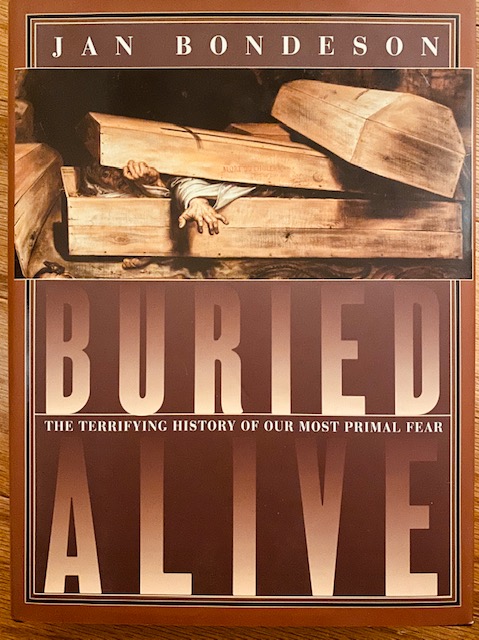

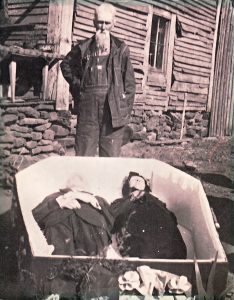

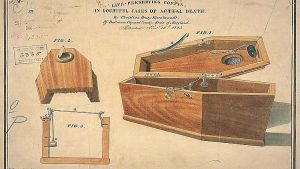

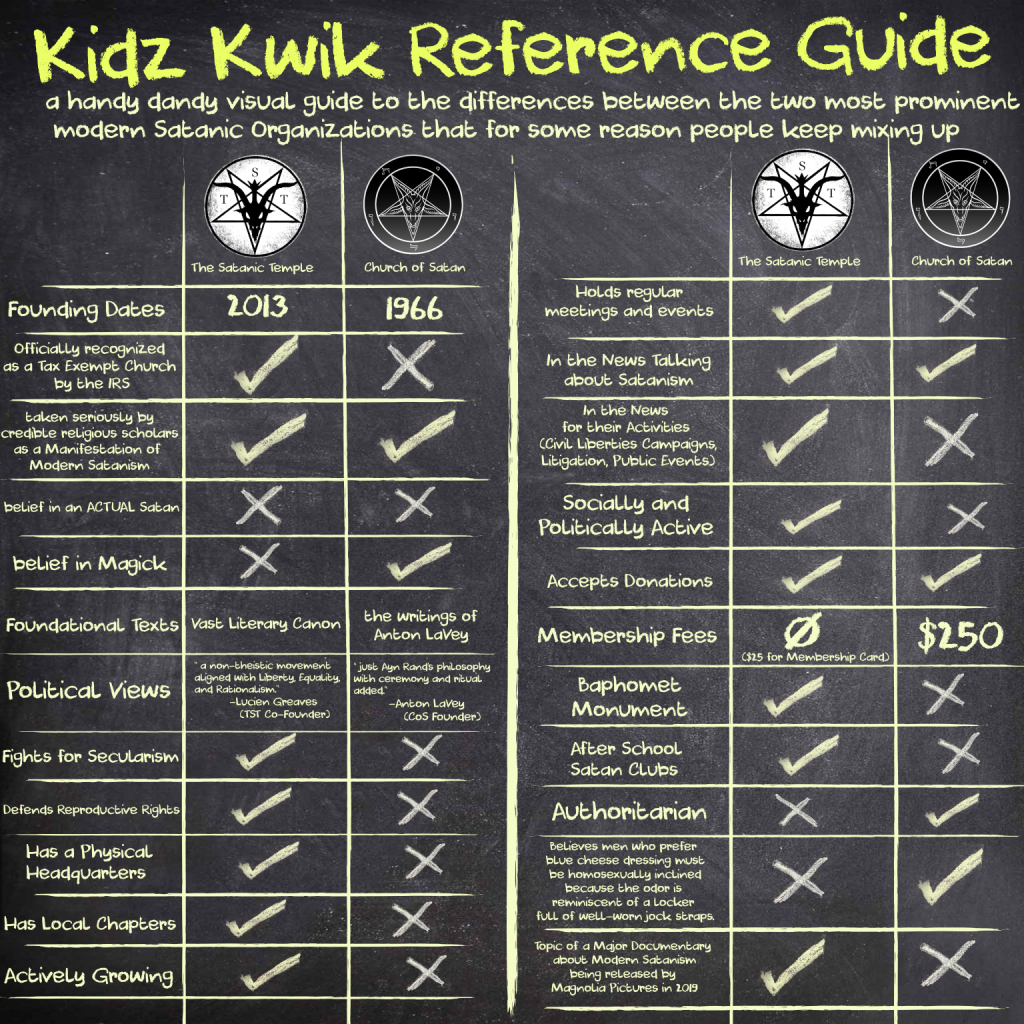

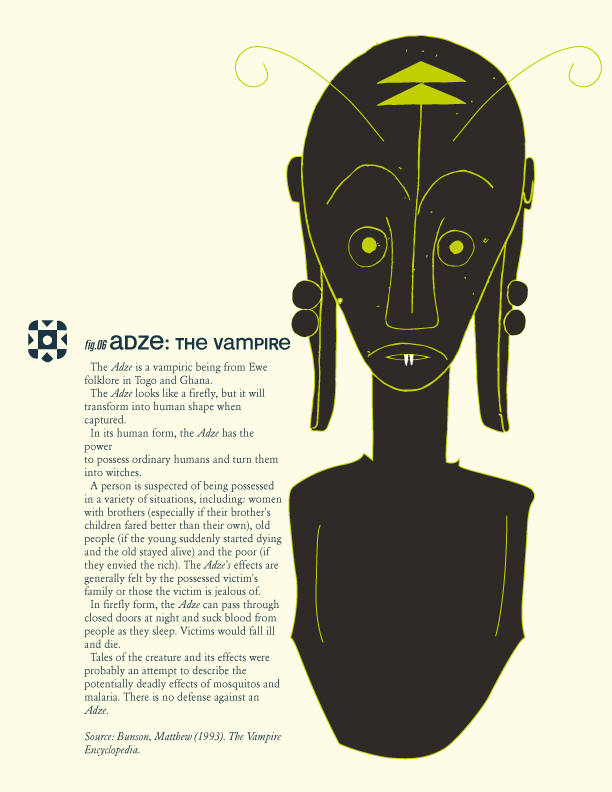

But that’s just the tip of the horror: evil witches, vampire bats, the walking dead, haunted houses, werewolves, and not-nearly-as-friendly-as-Casper ghosts. The scary side of the season is why the previous four blogs on this website have been about evil twins, being buried alive, satanism, and vampires.

Hard on the heels of Halloween comes Dia de Muertos, The Day of the Dead (though it seems to me it ought to be Days, plural). It begins at midnight on October 31 and continues through November 1 and 2.

- Writers please note:although November 1 and 2 coincide with the Catholic holidays of All Saint’s Day and All Soul’s Day, respectively, the Day of the Dead is not now tied to any particular religion. It is more of a cultural holiday than a religious one.

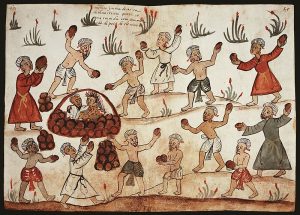

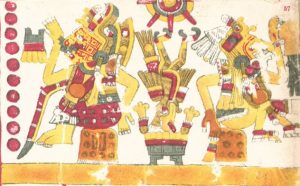

Scholars have traced the modern holiday back hundreds of years, particularly to an Aztec festival dedicated to the goddess Mictecacihuatl. People can, and have, personalized it, integrating elements into their own cultural and/or religious practices. It is nearly opposite of all that Halloween stands for.

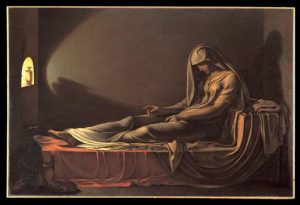

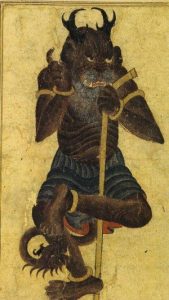

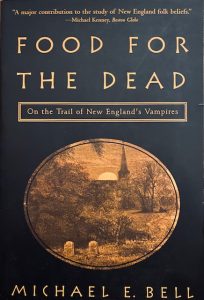

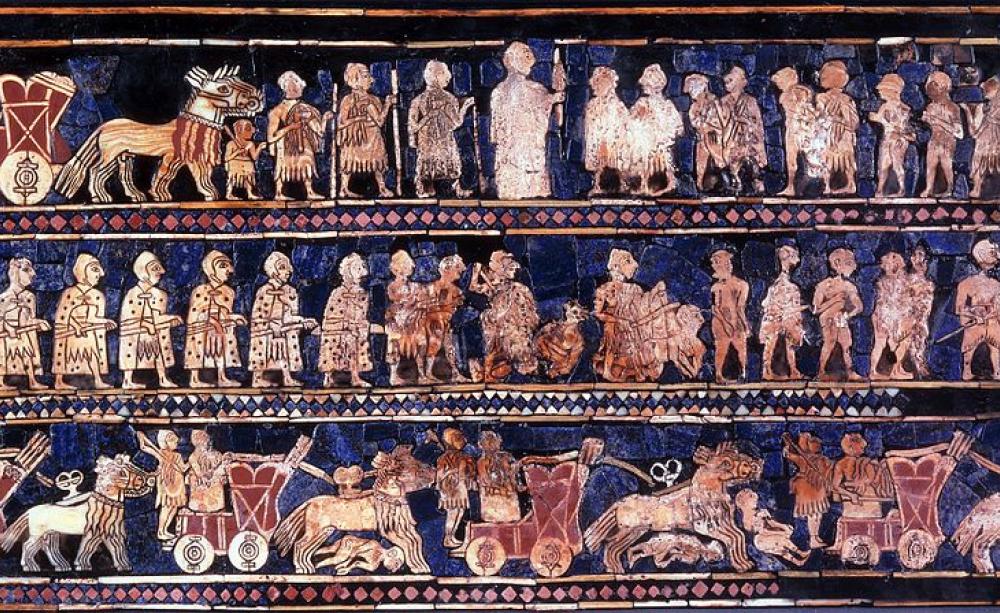

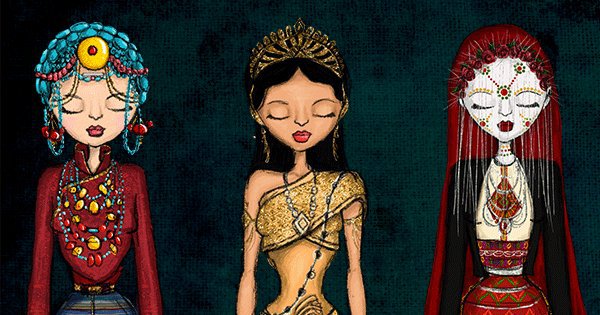

In Aztec mythology, Mictlan was the underworld and after-death destination for the majority of people. The ruler of Mictlan was

Mictlantecuhtli, who held the bones used to create all of humanity.

Mictlancíhuatl was his wife, who watches over the souls of the dead.

Dio de Muertos is celebrated throughout Mexico, especially the central and southern regions. It is also celebrated by people of Mexican heritage worldwide. Although the details of the celebration vary by location, the central elements are the same: celebrating the lives of those who have died with feasting, parties, costumes, and activities the dead enjoyed in life.

October 31 is usually devoted to preparing to welcome the souls of loved ones. A home altar is created, decorated with candles and lots of food and drink: fruits, peanuts, turkey mole, tortillas, and Day of the Dead breads (pan de muerto) ; sodas, cocoa, and water. These offerings are called ofrenda, though that can also refer to the altar itself. The breads often have icing that resembles and bones across the top. Buckets of flowers, especially wild marigolds (cempasúchitl), are used as well.

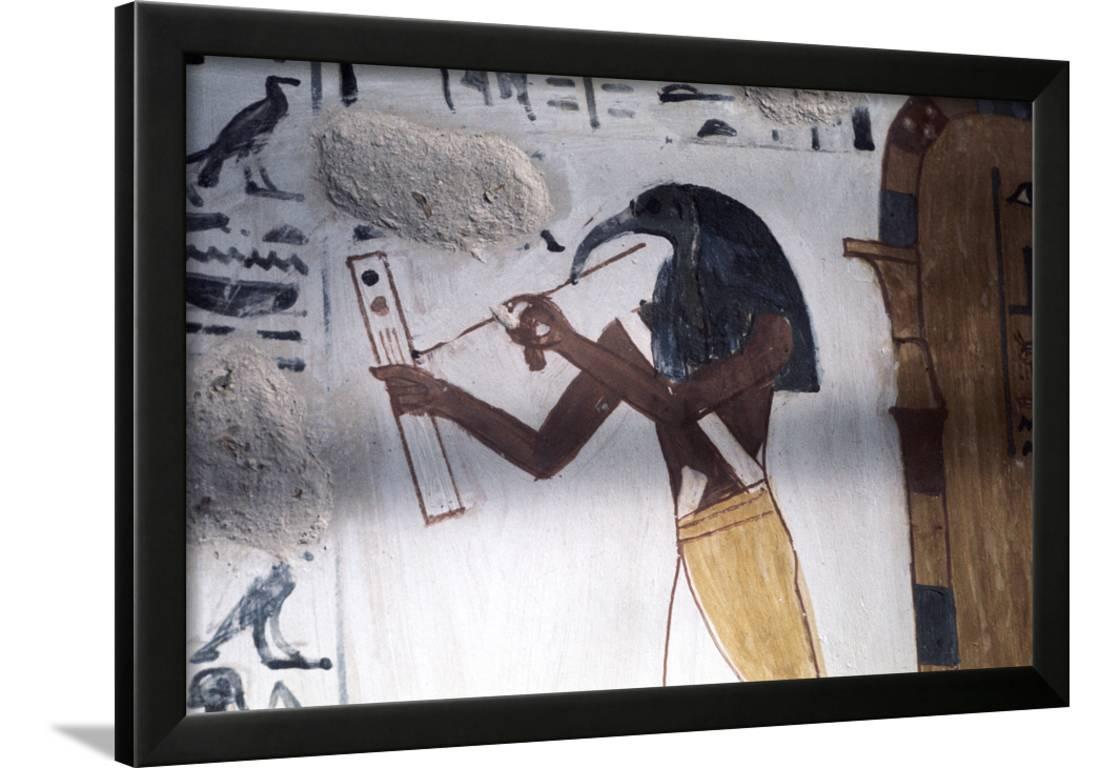

Copal incense was burned in Mesoamerica in ancient times.

The word copal is derived from the Nahuatl word copalli, which means “incense.”

Traditional altars include very specific elements, each with a distinct purpose.

- A candle for each relative remembers, so that the light will guide them.

- Flowers to represent the fleetingness of life.

- Salt and water to purify and refresh the souls tired from the journey.

- Copal incense to raise prayers to God.

- A photo or drawing of each relative, often with a favorite piece of clothing or toy.

The holiday begins when the souls of dead children and miscarried babies are allowed to return to their families for twenty-four hours, on Día de los Inocentes. Toys, candies, and miniature skulls are added to the home altars for these angelitos. On November 2, the spirits of adults arrive. The miniature skulls are replaced by full-sized ones. For adults, the altar includes cigarettes, shots of mezcal, and/or the favorite drink of the dead person(s).

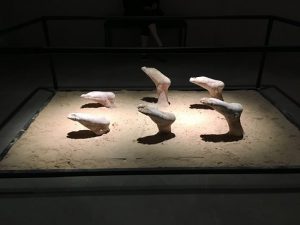

calavera de azucar (sugar skull) for a small child’s ofrenda

Sugar art was learned from Italian missionaries in the 17th century, who made sugar lambs and angels to adorn altars in Catholic Churches at Easter. Clay molded sugar skulls, angels, and sheep date back to the 18th century. As described on mexicansugarskull.com, “Sugar skulls represented a departed soul, had the name written on the forehead and was placed on the home Ofrenda [altar] or gravestone to honor the return of a particular spirit.” According to the same source, “Sugar skull art reflects the folk art style of big happy smiles, colorful icing and sparkly tin and glittery adornments.”

Now they are represented by jewelry and masks.

Typically, the holiday activities includes a trip to the cemetery/graveyard where loved ones are buried. Besides clean-up and maintenance of the gravesite, these visits include a party, often with local music, games, card playing, feasting, and decorating the graves.

Although a Mexican holiday, the Day of the Dead is celebrated worldwide. In the United States, Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona feature pretty traditional celebrations.

California, too, has strong historical ties to Mexico and Dia de Muertos is celebrated widely across the state—though the celebrations sometimes add a political element, such as an altar to honor the victims of the Iraq War.

Virtually every big city has a festival and events. For example, the historic Forest Hills Cemetery in Boston’s Jamaica Plain neighborhood hosts an annual festival celebrating the cycle of life and death. People bring food, flowers, pictures, and mementos to add to a huge decorated altar. It includes traditional music and dance.

Bottom line for writers: consider a scene involving Day of the Dead celebrations. Perhaps it is a tradition for one or more characters, or perhaps the protagonist just happens to be in a city where the celebration is taking place. Think broadly!