Attitude is a favorable or unfavorable reaction toward something or someone (often rooted in one’s beliefs and exhibited in one’s feelings and intended behavior). It is tempting to assume that there is a direct line between these favorable or unfavorable reactions and behavior. Good news for writers: people’s expressed attitudes seldom predict their actual behavior. This is because an attitude includes both feeling and thinking, and both affect behavior.

Attitudes predict behavior when these conditions are present:

- Social influences on what we say are minimal (little social pressure, fear of criticism). For attitudes formed early in life (e.g., attitudes toward authority and fairness) explicit and implicit attitudes often diverge, with implicit being a stronger predictor.

- Other influences our behavior are minimal: situational constraints, health, weather, etc.

- Attitudes specific to the behavior are examined: e.g., expressed attitudes toward poetry don’t predict enjoying a particular poem, but attitudes toward the costs and benefits of jogging predict jogging behavior.

- Attitudes are potent: stating an attitude and an intention to do something makes the attitude more potent and the behavior is more likely (recycling); asking people to think about their attitudes toward an issue also increases potency.

- Attitudes that are developed through direct experience are more accessible to memory, more enduring, and have a stronger effect on behavior.

Behavior affects attitudes when these conditions are present:

- Actions prescribed by social roles mold the attitudes of the role players. (Think prisoners and guards.)

- What we say or write can strongly affect subsequent attitudes. (Think being assigned a side in a debate.)

- Doing a small act increases the likelihood of doing a larger one later. (Think foot-in-the-door technique.)

- Actions affect our moral attitudes. We tend to justify whatever we do, even if it is evil.

- We not only stand up for what we believe in, we believe in what we have stood up for. (Think adopting a rescue animal or donating to a food drive.)

The question of whether government should legislate behaviors to change attitudes on a massive scale is compounded by the question of whether it is even possible.

Why does our behavior affect our attitudes?

- Self-Presentation Theory says people (especially those who self-monitor their behavior hoping to make a good impression) will adapt their attitude reports to appear consistent with their actions. Some genuine attitude change usually accompanies efforts to make a good impression.

- Dissonance Theory explains attitude change by assuming we feel tension after acting contrary to our attitude or after making difficult decisions. To reduce that arousal, we internally justify our behavior. The less external justification we have for undesirable actions, the more we feel responsible for them, thus creating more dissonance and more attitude change. (Think threat or reward.)

- Self-Perception Theory assumes that when our attitudes are weak, we simply observe our behavior and its circumstances and infer our attitudes (correctly or incorrectly) rather than the other way around. “How do I know what I think till I hear what I say?” And conversely, rewarding people for doing something they like anyway can turn their pleasure into drudgery—the reward leading them to attribute their behavior to the reward rather than the enjoyment of the behavior itself.

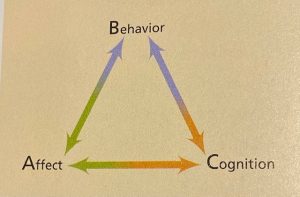

Bottom line for writers: to present a character’s attitudes to the reader, write what they are doing, thinking, and/or feeling. And note that each of these affects the other two and is affected in turn. Dissonance among the these creates lots of opportunity for tension, conflict, and misunderstanding!