And who would want to?

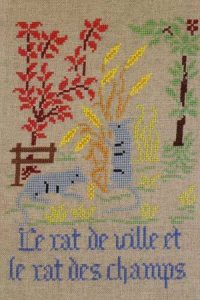

Writers, that’s who. Rats have long been characters—sometimes major—in literature old and new. Fables from around the world feature rats/mice and the moral usually relates to survival in one form or another. In these fables, rats are often presented as clever and resourceful. Aesop’s Fables, the Fables of Bidpai, and Panchatantra all feature rats involved in moral lessons.

In some languages, rats and mice are interchangeable. When there is a distinction made, rats usually come off worse. In fiction and in popular consciousness, rats are almost always portrayed as more devious or dirty than mice.

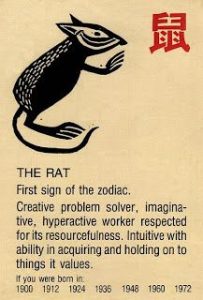

Rats are extremely important in Chinese mythology. The rat is the first of twelve animals in the Chinese Zodiac, corresponding to Sagitarius. Both are assigned the traits of creativity, hard work, generosity, and optimism.

The Year of the Rat is reputed to be one of prosperity and hard work. FYI: 2020 is a year of the rat. The rat rules daily from 11:00 p.m. till 1:00 a.m. and its season is winter.

N.B. writers: if you are inclined to write a rat fable, this might be the place to start.

Often rats are included in stories to add a touch of horror to scenes involving dungeons, torture chambers, vampires, the unknown… Authors from Edgar Allen Poe (“The Pit and the Pendulum“), to George Orwell (1984) to Stephen King (“Graveyard Shift” and “1922,” for example) have made effective use of rats. Shakespeare included rats in eight of his plays. Perhaps the epitome of horror would be The Coming of the Rats by George H. Smith (1961), suggesting the aftermath of the H-bomb.

And of course, if it’s in books, it’s in movies as well. Think Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade. Some movies, such as Ratatouille, Chicken Run, The Fantastic Mr. Fox, and Flushed Away, include rat characters who are funny and likeable in addition to being clever. Willard, Of Unknown Origin, and The Missing are Deadly are horror movies that focus on twisted relationships between humans and rats. Many films, especially The Food of the Gods, Deadly Eyes, Rodentz, and Rats: Night of Terror, focus on swarms of rats pitted against humanity.

If you do write about rats, it may help to know the terminology.

- A group of rats — a mischief

- Male rat — buck

- Female rat — doe

- Infants — pups or kittens

- Musophobia (suriphobia) — fear of rats and mice

Rats have such a horrific reputation that threats of being eaten, taken, overrun, etc., by rats are a common tool used around the world to frighten naughty children into better behavior. In Canada—Newfoundland—rat threats were second only to bear threats, and twice as frequent as big fish (in third place out of seven).

Writers consider the possibilities: “I’ve got an attic/cellar full of rats for naughty little girls and boys like you.”

As mentioned above, rats are often depicted as smart, and turn up in unexpected places. Consider this poem by Emily Dickinson:

The rat is the concisest tenant.

Emily Dickinson

He pays not rent—

Repudiates the obligation,

On schemes intent.

Balking our wit

To sound or circumvent,

Hate cannot harm

A foe so reticent.

Neither decree

Prohibits him,

Lawful as

Equilibrium.

Rat Facts

- Rats are everywhere in the world except Antarctica, where it’s too cold for them to survive outside and there are too few humans to provide for them.

- In some places, especially islands, aggressive rat control policies have reclaimed the land.

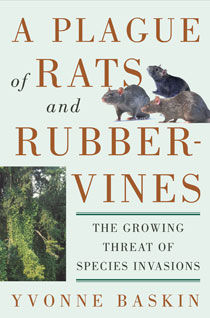

- Rats are one of the world’s worst invasive species.

- Transported around the world on ships, rats have been credited with the extinction of untold number of small native animals and birds.

- Rats often live with and near humans (commensals).

- Rats carry many zoonotic pathogens, all sorts from The Black Death to foot-and-mouth disease.

- Many rats in the wild live only about a year due to predation.

- By and large, rat vocalizations are pitched beyond the range of human hearing.

- Rats have been kept as pets at least since the late 1800s, most often brown rat species, and are no more of a health risk than cats or dogs.

- Rats are omnivorous.

- Rats are cannibals.

Rats as Food

The Bible forbids eating rats, and parts of the world, particularly in the Middle East, consider rat meat to be diseased, unclean, and socially unacceptable. Islam, Kashrut, the Shipibo people of Peru and the Sironó people of Bolivia all have strong taboos against eating rats. However the high number of rats and/or a limited food supply have brought rats into the diets of both humans and pets worldwide.

- Human food

- Rat meat is part of the cuisines of Vietnam, Taiwan, and Thailand.

- National Geographic (March 14, 2019) featured Vietnamese rat meat.

- In India, rats are essential to the traditional Mishmi diet, for women are allowed to eat only fish, pork, wild birds, and rats. In the Musahar community, rats are farmed as an exotic delicacy.

- Aboriginal Australians’ diet regularly included rats, as did traditional Hawaiian and Polynesian cultures.

- Rice field rats were an original component of paella in Valencia (the rat later replaced by rabbit, seafood, or chicken). These rats were also eaten in the Philippines and Cambodia.

- Rich people ate rat pie in England in Victorian times, and others ate rats during the World Wars when food was strictly rationed.

- Alcoholic rats trapped in wine cellars in France became part of a regional delicacy – grilled rats, Bordeaux-style.

- Rat stew was (and maybe still is) eaten in West Virginia.

- Animal food

- Snakes, both wild and pets, eat rats and mice. The rats are available to snake owners both live and frozen. However, in Britain, feeding any live mammal to another animal is against the law.

- When included in pet food, rats are counted as “cereals” in the ingredients list.

Rat Contributions to Science

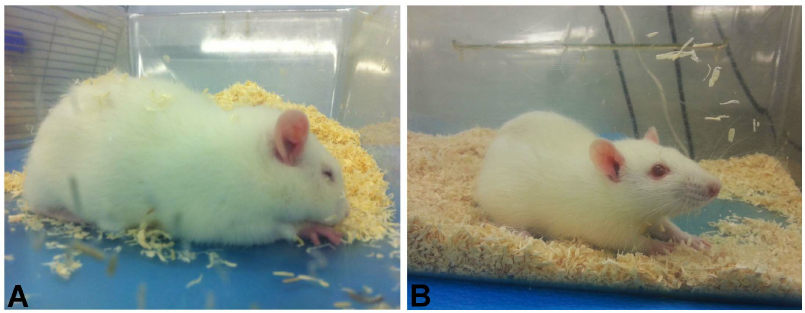

The first rat research I know of was conducted at Clark University (Worcester, MA) in 1895. Since then, rats have been used to study disease transmission, genetics, effects of diet, cardiovascular conditions, and drug effects.

Psychologists have studied rats to further our understanding of learning, intelligence, drug abuse, ingenuity, aggressiveness, adaptability, and the effects of overcrowding (the “behavioral sink”).

Working Rats

Besides acting in movies, rats are good a sniffing out gunpowder residue, land mines, and tuberculosis. They also can be trained for animal-assisted therapy.

N.B. writers: consider a PI or amateur detective who has a trained rat sidekick!

The stereotypic rat: Besides the horror aspects of ratness, their image is mainly that of pest.

They infest urban areas, particularly multi-family housing. They like areas with access to food, water, and a moderate environment, such as under sinks, near garbage, in walls, cabinets, or drawers.

In rural areas, rats are a threat to both grain supplies and small birds. (Think chicks.) They live in fields, barns, cellars, basements, and attics.

And as with so many things, rats are a bigger bane for the poor, whether rural or urban. Picture this: a baby crib is set in the middle of a room, all four legs in buckets of water to try to keep rats and mice from climbing into the crib. Meanwhile, beady eyes stare from darkened corners.

Rat in Everyday Language

Any way you cut it, rat is not positive.

- Noun: backstabber, betrayer, blabbermouth, canary, deep throat, double-dealer, fink, informant, sneak, snitch, source, squealer, stoolie, stool pigeon, tattler, turncoat, whistle-blower.

- In unionized workplaces, anyone who doesn’t pay dues and/or crosses picket lines is called a rat.

- Verb: the act of doing any of the above.

- Rats!—exclamation of surprise, frustration

- Drowned rat

- Gutter rat

- Mall rat

- Rat’s ass (as in, I don’t give a…)

- Rat faced

- Rat fink

- Rat hole

- Rat king

- Rat’s nest (hair or residence)

- Rat pack

- Rat race

- Rats from a sinking ship

- Rat tail (hairstyle)

- Rat tail comb

- Ratted hair

- Rat trap

- Ratty

- Smell a rat

Bottom line for writers: it’s worth your while to know about rats!