I’m a fan of history—not so much the names and dates of battles and rulers, but the lives of ordinary people. I might say it’s a sociological and/or anthropological approach to history. I was fascinated by Anne Frank—what she wrote and how she lived—long before I visited the Anne Frank House in Amsterdam a few years ago.

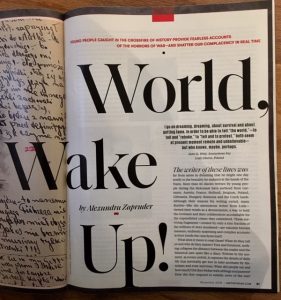

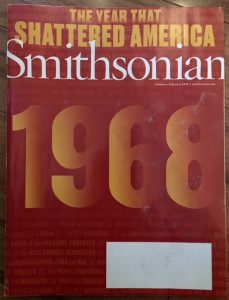

So, of course the cover of the November 2018 Smithsonian magazine caused me to snatch it up. Pages 39-88 are devoted to bringing us voices from the past, long silenced by war.

This page summarizes the point of this coverage: Never forget, lest we repeat the devastations of the past. This month marks the 80th anniversary of Kristallnacht, so the publication is particularly timely.

The first article recounts the twisted path by which a Holocaust diary showed up in the United States. Renia Spiegel, a 15-year-old girl in a small Polish town, wrote a diary. Her diary survived her death almost by accident, and had a profound effect on the lives of others.

The diary was published in Polish in 2016, but is translated into English and published in Smithsonian for the first time. Renia Spiegel was a teenager, not a trained writer, but her words are as powerful an Anne Frank’s, conveying the commonplace, day-to-day against the backdrop and ever impinging horrors of WWII. The diary is a gripping eye-witness record of history in prose, poetry, and sketches.

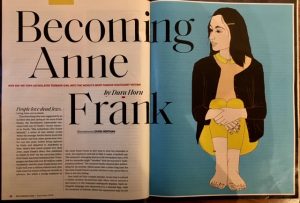

Just after the diary translation, the article by Dara Horn is thought-provoking exploration of the contradictions in attitudes and behaviors that surround people’s reactions to Jews and Jewishness. It includes a quote from Elie Wiesel: “Those of us who went through the war and tried to write about it… become messengers. We have given the message and nothing changed.” Wiesel was a prisoner in Buchenwold when the camp was liberated in April 1945.

In Lithuania, beginning in 1940, Matila Okin kept a diary of her life and times as a Jew in wartime Europe. Her poetry was published in literary journals and her work solicited by editors, and several are included in the article, which also talks about the Catholic priest who hid Okin’s notebooks in the wall of the church before the Soviets deported him to Siberia.

The last of the articles quotes from diaries written in the Lodz Getto in Poland, but also U.S. internment camps, Bosnia during the Serbian aggression, Syria, Iraq, and considers the impact of today’s digital war diaries.

Bottom line: This Smithsonian makes clear that history isn’t dead—and testifies that it isn’t even past. Every writer should read it.