In October, I think of bones. And what uses might bones have besides holding up human and animal bodies? This week’s blog is the first of my October bone series.

Wind Chimes

Archeological evidence of wind chimes dates back almost 5000 years. They were first used in Asian, Mediterranean, and Egyptian civilizations. In South East Asia, historians have found remains of wind chimes made from bone, wood, bamboo, shells, jade, and bronze in about 3000 BCE. Ancient peoples may have thought chimes warded off evil spirits. A more practical use in Indonesia was to scare birds from crops.

Different cultures attribute unique meanings to wind chimes:

- Protection & Warding Off Negativity – Ancient Rome, China, and Japan

- Good Luck & Prosperity – Feng Shui, Hindu temples, and business entrances

- Healing & Meditation – Used in sound therapy, yoga, and spiritual rituals

- Remembrance & Tribute – Common in memorial gardens and sympathy gifts

Today, you can still buy bone wind chimes, for example, on Etsy at prices ranging from $30 to $300.

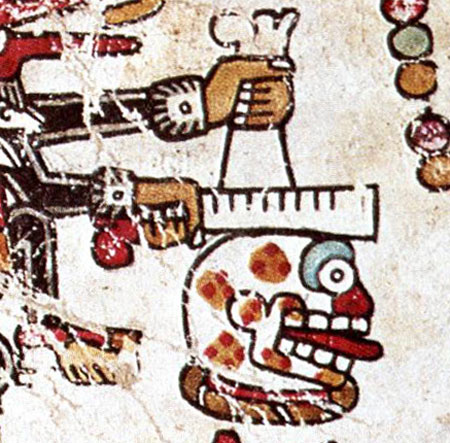

Musical Rasps (Omichicahuaztli)

The musical rasp originated in Mesoamerica. It consists of a dried, striated deer bone or human femur that is scraped by a smaller bone to produce doleful sounds for the accompaniment of funeral dirges. Musicians sometimes held them above a resonating chamber, such as a conch shell or a skull, to amplify the sound. Amazing, what people will do to make music!

Some might quibble over calling it music. According to anthropologist Walter Krickeberg, Nahuatl people may have restricted funeral ceremonies to a sung dirge and the bone music of the omichicahuaztli, which he argues does not qualify as music.

What is not in dispute is the use of these instruments prior to the Spanish invasion.

“Several commentators have noted that instruments similar to the omichicahuaztli have continued to be used in modern times amongst the indigenous peoples of NW Mexico and SW United States, such as the Tarahumara (Rarámuri), Huichol, Pima, Hopi…), in some cases as magic instruments for bringing success in hunting, in others as medicinal tools used by shamans to speed a person’s recovery from illness.”

Ian Mursell, MexicoLore

Flutes

Flutes, made of bone and ivory, represent the earliest known musical instruments, clear evidence of prehistoric music. Archaeologists have discovered several such flutes in caves in Germany, dating to the European Upper Paleolithic, products of the Aurignacian culture.

The vulture bone flute was not alone in Hoel Fels Cave. Specifically, archaeologists have also found two flutes made of mute swan bone and one made of wooly mammoth ivory.

Flutes made of bone, horn, ivory, etc. are available today online.

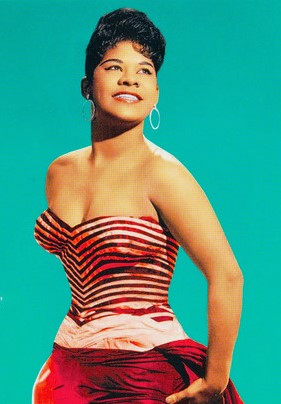

Bones

Mostly made of wood today, in their most basic form, bones are sections of animal rib bones—usually sheep or cow—between 5 and 7 inches long. Players hold them between their fingers, curved sides facing each other, and knock them together with flicks of their wrists. Experts can create a vast range of percussive sounds. You may have heard bones without realizing it.

In 1949, Freeman Davis, known as “Brother Bones,” recorded a version of the Jazz Age standard “Sweet Georgia Brown,” which became famous after the Harlem Globetrotters picked it up as their theme song three years later.

The bones have their roots in traditional Irish and Scottish music, and immigrants from those countries brought them to America, where they found a home in bluegrass and other folk genres. They’re similar to other clacking percussion instruments like the spoons, the Chinese paiban, and castanets.

Fun fact: Don’t confuse playing the bones with Bones playing! Nah’Shon Lee “Bones” Hyland, a former star of the VCU basketball team, plays for the Minnesota Timberwolves!

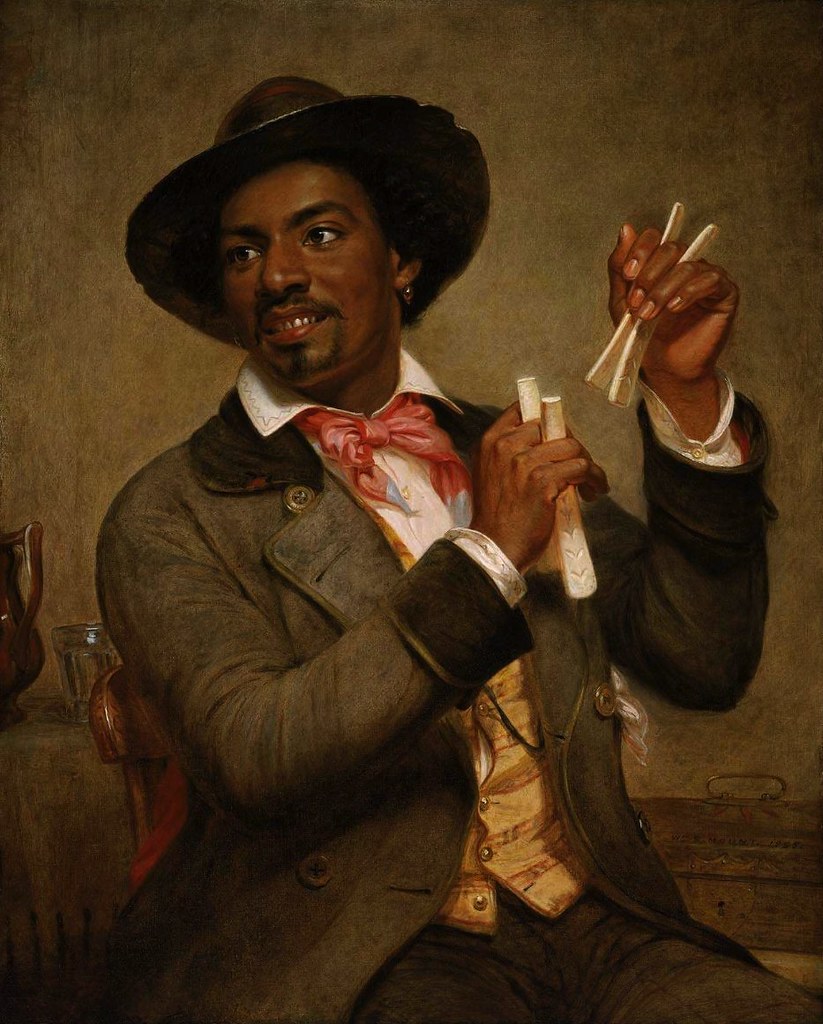

Jawbone (Quijada, Charrasca)

The jawbone as a musical instrument originated in Africa. It’s usually the jawbone of a zebra—or donkey, horse, mule, or cow—stripped of all flesh and dried to make the teeth so loose that they rattle around in their sockets. The jawbone came to the Americas along with the slave trade and was historically used in early American minstrel shows.

But it’s more than a simple rattle — players can create other sounds by striking the jawbone with a stick or rubbing wood across its teeth. Suz Slezak demonstrates several of these techniques here. Musicians use the jawbone throughout most of Latin America, including Mexico, Peru, El Salvador, Ecuador, and Cuba.

Fun fact: Martin B. Cohen designed the vibraslap to sound exactly like actual jawbones but with sturdier materials. He patented his design in 1969.

Bone Guitar

Artist Bruce Mahalski and guitar maker David Gilberd teamed up to build a bone guitar that features about 35 skulls. Super metal, yes, but not quite bony enough. It’s still, at its heart, a guitar. As far as I know, no such instruments are available for sale!

Bottom Line: Your skeleton does more than hold up your body. Human ingenuity has led people to create bone music!