Who comes to mind? Chances are it’s such Pulitzer Prize winners as fiction writers Alice Walker, Toni Morrison, and Colson Whitehead.

“From the first African-American Pulitzer winner — Gwendolyn Brooks in 1950 — to more recent winners such as Tyehimba Jess, Lynn Nottage and Colson Whitehead, these writers’ creative interpretations of black life are rooted in research and history.” (pulitzer.org)

Since that 1950 first, there have been six African American Pulitzer Prize winners in poetry (including Tracy K. Smith, the Poet Laureate of the U.S. from 2017 to 2019), four in drama, and a special citation for Alex Haley, author of Roots.

So far, the only Black American to win a Nobel Prize in literature is Toni Morrison, in 1993.

These recent accolades have grown from deep historical roots.

Early Examples of Poetry and Fiction

Lucy Terry Prince, often credited as simply Lucy Terry (1733–1821), was an American settler and poet. As an infant, she was kidnapped in Africa and sold into slavery in the colony of Rhode Island. Obijah Prince, her future husband purchased her freedom before their marriage in 1756. She composed a ballad poem, “Bars Fight”, about a 1746 altercation between white settlers and the native Pocomtuc. This poem was preserved orally until being published in 1855. It is considered the oldest known work of literature by an African American.

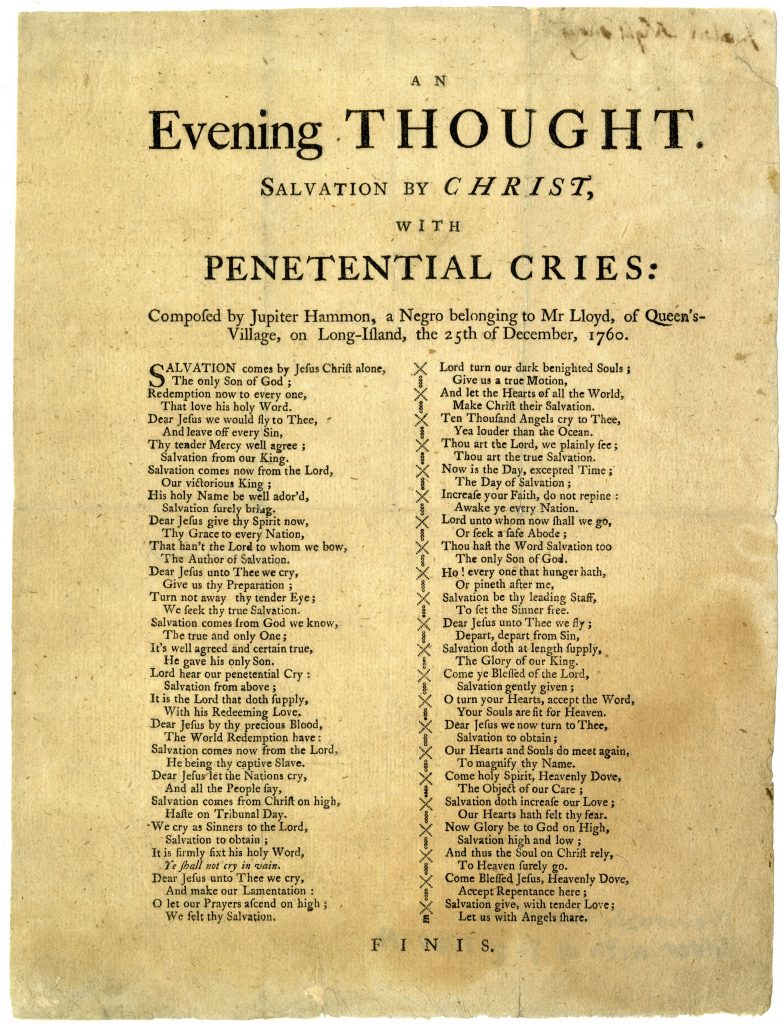

Another early African-American author was Jupiter Hammon (1711–c1806), enslaved as a domestic servant in Queens, New York. Hammon, considered the first published Black writer in America, printed his poem “An Evening Thought: Salvation by Christ with Penitential Cries” as a broadside in early 1761. His speech “An Address to the Negroes in the State of New York” (1787) may be the first oration by an African American speaker that was later published. In 1778 he wrote an ode to Phillis Wheatley, in which he discussed their shared humanity and common bonds.

possibly by Scipio Moorehead

The poet Phillis Wheatley (c. 1753–1784) published her book Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral in 1773. This first book aimed to prove that “Negros, Black as Cain,” were not inherently inferior to whites in matters of the spirit and thus could “join th’ angelic train” as spiritual equals to whites. Her mastery of a wide range of classical poetic genres, Greek and Latin classics, history, British literature, and theology proved that claims that only Europeans were capable of intelligence and artistic creation were patently false. Members of the Abolitionist movement embraced Wheatley’s literary prowess, which combined elements from many genres of poetry with Gambian elegiac forms and religious themes to create work that was read and shared by people on both sides of the Atlantic. In addition to being the the first African American to publish a book, Wheatley was the first to achieve an international reputation as a writer. Selina Hastings, the Countess of Huntington, was so impressed by Phillis Wheatley’s skill that she gave the financial support to publish Wheatley’s book in London.

Victor Séjour (1817–74) wrote “The Mulatto” (1837), the first published work of fiction known to have an African American author. Juan Victor Séjour Marcou et Ferrand was an American Creole of color and expatriate writer. Born free in New Orleans, he spent most of his career in Paris and published his fiction and plays in French. “The Mulatto” did not appear in English until the Norton Anthology of African American Literature was published in 1997.

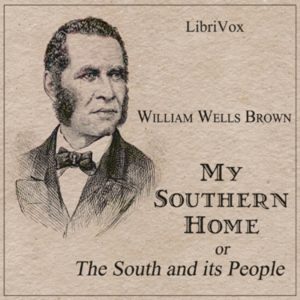

In 1853 William Wells Brown, an internationally known fugitive slave narrator, authored the first Black American novel, Clotel; or, The President’s Daughter (1853). The story centers around two mixed-race women fathered by Thomas Jefferson and held in slavery in Monticello. Like Phillis Wheatley’s poetry, Brown’s book was first published in London. Inspired by the success of Frederick Douglass’s work, Brown published Narrative of William W. Brown, a Fugitive Slave, Written by Himself in 1845, detailing his early life in Missouri and his escape from slavery. In 1858, he wrote The Escape, the first play written by an African American author to be published in America.

Frank J. Webb’s 1857 novel The Garies and Their Friends, was also published in England, with prefaces by Harriet Beecher Stowe and Henry, Lord Brougham (Lord High Chancellor of England). It was the first work of fiction by an African-American author to portray passing, a mixed-race person deciding to identify as white rather than black. It also explored northern racism, in the context of a brutally realistic race riot closely resembling the Philadelphia race riots of 1834 and 1835. Webb published his novel in London, where he and his wife lived between 1856 and 1857.

In 1859—still pre-Civil War—Harriet E. Adams Wilson wrote the first novel by a Black person that was published in the United States, in Boston. She claimed to have written the book with the sole purpose of earning enough money to survive. Our Nig; or Sketches from the Life of a Free Black, In a Two-Story White House North, Showing that Slavery’s Shadow Falls Even There, was largely autobiographical, and most of what scholars know about “Hattie” Wilson is derived from her novel. The story of Our Nig centers around a mixed-race woman in New England, discussing the racism and abuse that went on even in the nominally free states of the North. The publishing world largely assumed her novel to have been written by a white author until scholarship by Henry Louis Gates, Jr proved the author to have been an African American woman.

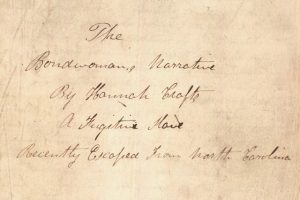

A recently discovered work of early African-American literature is The Bondwoman’s Narrative, which was written by Hannah Crafts between 1853 and 1860. Crafts was born into slavery in Murfreesboro, North Carolina in the 1830s but escaped to New York around 1857. Her book has elements of both the slave narrative and a sentimental novel. If her work was written in 1853, it would be the first African-American novel written in the United States. The Bondwoman’s Narrative also has the distinction of being the only novel entirely untouched by white editors, presenting the author’s thoughts without being filtered to be palatable to a white audience. The novel was published in 2002.

Autobiographies

Early African-American spiritual autobiographies were published in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, preceding the slave narratives. I won’t delve into those here, except to say that authors of such narratives include James Albert Ukawsaw Gronniosaw, John Marrant, George White, Zilpha Law, Maria W. Stewart, Jarena Lee, Nancy Gardner Prince, and Sojourner Truth.

According to Wikipedia, “The slave narratives were integral to African-American literature. Some 6,000 former slaves from North America and the Caribbean wrote accounts of their lives, with about 150 of these published as separate books or pamphlets. Slave narratives can be broadly categorized into three distinct forms: tales of religious redemption, tales to inspire the abolitionist struggle, and tales of progress. The tales written to inspire the abolitionist struggle are the most famous because they tend to have a strong autobiographical motif. Many of them are now recognized as the most literary of all 19th-century writings by African Americans.”

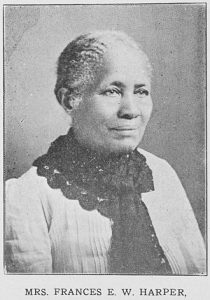

Frances E. W. Harper (1825–1911), born free in Baltimore, Maryland, wrote four novels, several volumes of poetry, and numerous stories, poems, essays and letters. She was an abolitionist, suffragist, co-founder of the National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs, and the first African American woman to publish a short story. She was also the first woman instructor at Union Seminary in Ohio. Her book Poems on Miscellaneous Subjects, self–published in Philadelphia in1854, sold more than 10,000 copies within three years.

Harriet Jacobs (1813 or 1815 – March 7, 1897), born into slavery in Edenton, North Carolina, was the only woman known to have left writing that documents that enslavement. Her autobiography, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, written by Herself, published in 1861 under the pseudonym Linda Brent, is now considered an “American classic”. For most of the twentieth century, critics thought her autobiography was a fictional novel written by a white author. Jacobs’ autobiography is one of the only works of that time to discuss the sexual oppression of slavery, which led many publishing companies to refuse her manuscript; she finally purchased the plates and had the book printed “for the author” by a printing firm in Boston.

Other African-American writers also rose to prominence in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

- Charles W. Chesnutt, was a well-known short story writer, novelist, and essayist. He wrote many works dealing with social and racial identity in the American South after the Civil War.

- Paul Lawrence Dunbar, who mixed mainstream English and the dialect of rural, Black communities, was the first African-American poet to gain critical acclaim and national prominence. His first book of poetry, Oak and Ivy, was published in 1893.

- Mary Weston Fordham published a book of poetry in 1897, Magnolia Leaves. She worked as a teacher for the American Missionary Society, and many of her poems contain spiritual themes, as well as references to family and historical events.

- Elizabeth Keckley was born into slavery and became a friend of Mary Todd Lincoln and head of the Department of Sewing and Domestic Science Arts at Wilberforce University in Ohio. Her book Behind the Scenes; or, Thirty Years as a Slave and Four Years in the White House, focused her narrative on the incidents that “moulded her character,” and on how she proved herself “worth her salt.” It details her life in slavery, her work for Mary Todd Lincoln and her efforts to obtain her freedom.

After the Civil War

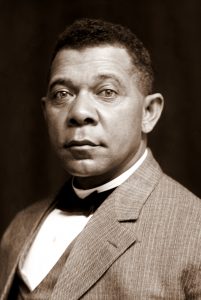

One of the most influential authors of this period is Booker T. Washington (1856–1915). Among his published essays, lectures, and memoirs are Up From Slavery (1901), The Future of the American Negro (1899), Tuskegee and Its People (1905), and My Larger Education (1911). Booker Taliaferrro (he adopted the surname Washington later in life) was born into slavery in Virginia and attended school while working in a coal mine, eventually graduating from Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute. He was the founder and first president of Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute (now Tuskegee University). Advisor to may presidents, he is the first African American to appear on a U.S. postage stamp, or to be invited to dine at the White House.

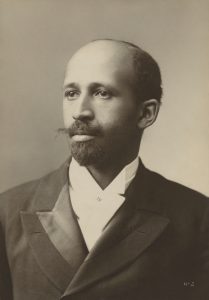

W. E. B. Du Bois (1868–1963), in addition to being one of the most prominent post-slavery writers, was also a sociologist, socialist, lecturer, historian, and civil rights activist. In 1903 he published an influential collection of essays entitled The Souls of Black Folk in which he wrote, “The problem of the twentieth century is the problem of the color-line.” He drew from his personal experience growing up in rural Georgia to describe how African Americans lived within American society. William Edward Burghardt Du Bois completed graduate work at the Friedrich Wilhelm University (Berlin, Germany) and earned a doctorate in philosophy from Harvard University. Du Bois was one of the original founders of the NAACP in 1910.

The Norton Anthology of American Literature (Fourth Edition, Volume 1) spanning the colonial period to the Civil War, includes biographical information and samples of the works by Phillis Wheatley, Harriet Jacobs, and Frederick Douglass. Volume 2, which surveys the years since the Civil War includes biographical information and writing samples from Washington and Du Bois, as well as more than a dozen other Black U. S. writers.

Bottom line: There’s much more to writing by Black Americans than the big name fiction writers (great as they are)!