Several professions, including—but not limited to—doctors, trainers, physical therapist, dancers, and athletes are hyper aware of bones. But bones are important to everyone for simply living and functioning. So let’s show bones a little love!

Check out the rest of my October bone series: Bone Music, Bone Eating, and Fortune Telling Bones!

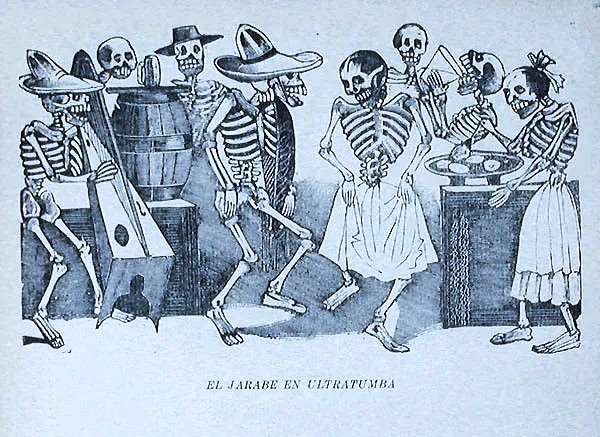

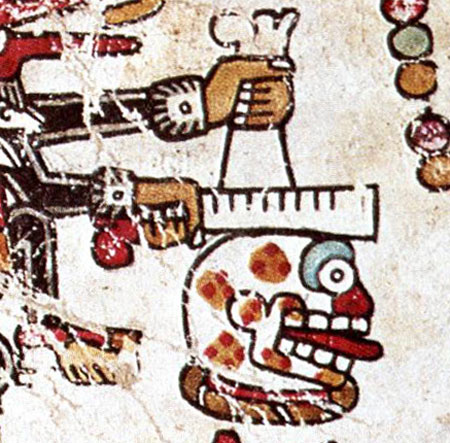

Metaphorical Bones

Basically, a metaphor is when the meaning isn’t what the words literally say. Writers are very aware of the value of metaphors, but they are more prevalent in our everyday lives than we might think. Bones are very useful this way!

No backbone/spineless: lacking courage or willpower

Boneheaded: a stupid person, a dunce

A bone to pick with you: wanting to discuss a problem or grievance

Bone of contention: a point of disagreement, matter of dispute

Bag of bones: very thin, skinny

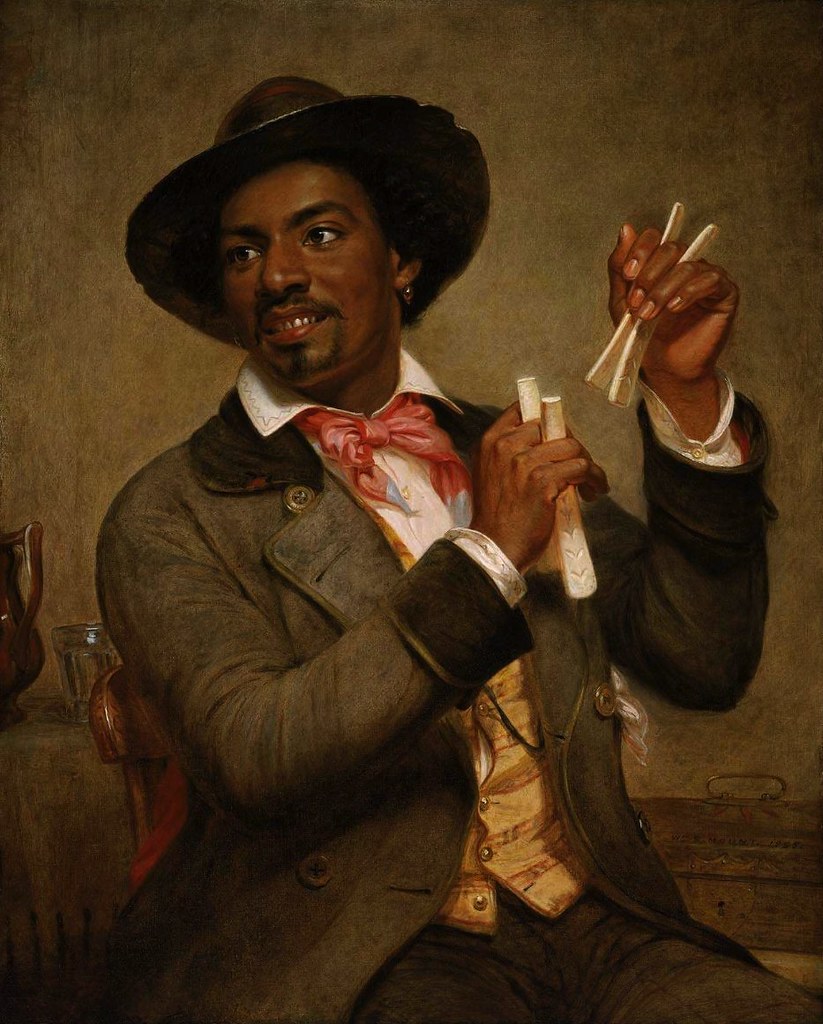

Sawbones: a physician, especially a surgeon

No bones about it: to speak frankly or directly, no hesitation or evasion, to emphasize certainty

Funny bone: a point on the elbow, nerve close to the surface, which when struck produces a tingling sensation; sense of humor (as in, that joke tickles my funny bone)

Bare bones: essentials, basic elements, no details

Bone chilling: extremely cold, causing feelings of fear or terror

Boner: embarrassing mistake, an erection

And One Step Removed:

Jawing: scolding, clamorous, or abusive talk

Knuckle-dragger: strong but dimwitted

Glass jaw: vulnerability physical (e.g., a boxer easily knocked out) or more metaphorical (a public figure’s vulnerability to destructive criticism)

Weak-kneed: lacking willpower, strength of character, or purpose, timid

Functional Bones

Bones are absolutely essential for survival, movement, and health.

They protect internal organs from impact injury, especially the brain and heart.

They produce white blood cells to fight infection.

Bone marrow produces red blood cells to carry oxygen.

Bones literally hold up the body and keep it from collapsing to the ground. Your posture depends on your bones.

Certain types of bones store fat and then release it when your body needs energy.

Bones can also store necessary minerals when their blood levels are too high. They release these minerals when the body needs them. Examples include calcium, phosphorus, and vitamin D.

Problem Bones

When things go wrong with bones, they can go very wrong indeed.

Arthritis. A painful condition where the joints wear down, causing inflammation in the joints.

Scoliosis. This is when the bones in the spine are no longer straight. Sometimes called curvature of the spine.

Cancers. Unfortunately, there are certain cancers that can form inside of your bones and impact your skeletal system.

Breaks. Bones can break — sometimes very badly. Although your bones can heal breaks on their own, people typically need medical help to help a broken bone heal properly.

Osteoporosis. Bone resorption disease characterized by thinning of bone tissue and decreased skeletal strength. It is the most common reason for broken bones among the elderly.

Healing Bones

A broken bone can seriously hinder one’s ability to function, particularly a broken arm or leg. Fortunately, our bones can almost always heal themselves.

- Bones repair themselves so quickly that you have a new skeleton about every seven years.

- Arms are among the most commonly broken bones, accounting for almost half of all adults’ broken bones.

- The collarbone is the most commonly broken bone among children.

- Most broken bones heal on their own — blood vessels form in the area almost immediately after you break it to help the healing process begin. Within 21 days, collagen forms to harden and hold the broken pieces in place. A cast or brace only ensures the bone heals straight to avoid more problems in the future.

Fun Facts About Bones

This section is included because it is just so interesting—at least to me!

- Technically, tooth enamel is bone, the strongest in the body.

- The adult human body has 206 bones (some say up to 213), but infants have many more: 270-300 or so.

- A 13th rib is rare — only 0.2% to 0.5% of people are born with it. This extra rib, called a cervical rib, can cause medical issues like neck pain, so people born with this extra rib often have it removed.

- More than half the bones in the body are in the hands and feet. Each hand has 27 bones, while each foot has 26. Together, that’s a combined 106 bones.

- The femur, or thighbone, is the longest and strongest bone of the human skeleton.

- The stapes, in the middle ear, is the smallest and lightest bone of the human skeleton.

- Bones stop growing in length during puberty. Bone density and strength will change over the course of a lifetime, however.

- The upper arm bone is called the humerus, which gives the “funny bone” its name. In reality, anytime you bang your elbow, it’s the ulnar nerve causing the tingling feeling.

- The only bone in the human body not connected to another is the hyoid, a V-shaped bone located at the base of the tongue. It anchors the tongue and helps you speak and swallow. It’s held in place by ligaments, muscles, and cartilage

Bottom Line: There are things about bones that anyone can and everyone should appreciate.