When my three children were young, we always carved three Jack-O-Lanterns on Halloween. (FYI: The traditional pumpkin for American Jack-O-Lanterns is the Connecticut field variety.) If my family of origin had a crest, our motto would be “Waste Not, Want Not.” Of course, I couldn’t just throw away perfectly edible food! This combination of personality and plenty resulted in lots of pumpkin for our table.

Culinary Uses

The day after Halloween, we “dealt with” those pumpkins. At the time, this meant chunking them up, baking the pieces, pureeing, and freezing the pulp in two-cup freezer bags. (Full disclosure: Jack-O-Lantern pumpkins are far from the best eating ones. Sugar pie pumpkins or Long Island Cheese pumpkins are preferred by pumpkin connoisseurs.) The bounty led me to cut recipes from can labels, ask for favorite recipes from family members, and buy cookbooks like this.

Between then and now, I’ve learned just how narrow my culinary use of pumpkins had been.

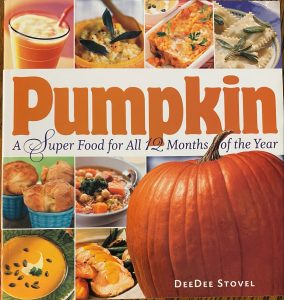

In word associations tests, “pumpkin” is almost certain to be followed by “pie.” And sure enough, I have at least a dozen excellent pumpkin pie recipes. And then there is pumpkin bread, pumpkin stew, pumpkin curry, pumpkin lasagna, pumpkin beer, pumpkin butter, pumpkin muffins, pumpkin pancakes… Pumpkin smoothies are a current favorite.

FYI: Pumpkin can be substituted for other winter squash in virtually any recipe. In fact, the FDA does not distinguish between pumpkins and other varieties of squash. When you buy a can of “pumpkin” from the grocery store, it’s just as likely to be acorn or butternut squash inside.

Pumpkins grow worldwide. Antarctica is the only continent that can’t grow pumpkins. (Those poor penguins…)

- Blossoms cooked with duck were and are a Chinese delicacy

- Small, green pumpkins can be treated like summer squash

- Leaves can be eaten by themselves or dressed in a salad

- Whole pumpkins stuffed and baked (sweet or savory)

- As a complement to meat in stews (especially in Native American, African, and South American recipes)

- Slices fried with apples, sweet herbs and spices, and currants

- With corn and beans as succotash (Native American)

- Dried/dehydrated; sometimes pounded into powder for baking

- Seeds:

- Popular with pre-Columbian people of Mexico and Peru; now available in most grocery stores

- Oil from seeds

- Butter (like apple butter)

- Beer/fermented drinks

- As a hard times substitute for other ingredients

- E.g., pumpkin syrup for molasses, pumpkin sugar)

Pumpkin shells can even be used a type of slow-cooker. After the stringy guts have been scooped out, they can be filled and buried in ashes or baked in an oven. Armenian rice pudding baked in a pumpkin shell is a particular holiday delicacy.

Native Americans (Iroquois in particular) had Four Sisters of agriculture: pumpkins, corn, beans, and squash, interplanted so each vegetable provided sustainability and nutrients for the others to grow. The four sisters of agriculture allowed the survival the earliest colonists. The ubiquity—and importance of pumpkins is clear in this old New England doggerel:

From pottage, and puddings, and puddings, and pies,

Our pumpkins and parsnips are common supplies.

We have pumpkins at morning, and pumpkins at noon;

If it were not for pumpkins, we should be undone.

Non-Culinary Uses

- Stacked on thatched roofs to provide stability

- South Africa soap

- As a medium of currency (1 pumpkin for 4 cocoa beans, etc.)

- Food for livestock, from chickens to pigs

- As an offering to deities in China during the season of the Fifth Moon

- As a dietary supplement for cats and dogs that have certain digestive ailments such as hairballs, constipation, and diarrhea

- In Native American medicine to treat intestinal worms and ailments

- In Germany and southeastern Europe to treat irritable bladder and benign prostatic hyperplasia

- In China for the treatment of parasitic disease and the expulsion of tape worms

- Hollowed out and lighted with candles, as lanterns to light the way after dark

And Then There is Halloween

The tradition originated with the ancient Celtic festival of Samhain, an important day for Druids, when the veil between this world and the afterlife was particularly thin. People would light bonfires and wear frightening costumes to ward off ghosts. All Hallows Eve (the night before All Saints Day) transmuted to Halloween—holy or hallowed evening.

Historically, in Britain and Ireland lanterns were carved from turnips or other vegetables. In the New World, pumpkins were a substitute, and even better because they are bigger and easier to deal with. Although other vegetables are still popular in Scotland and Northern Ireland, Britain purchases millions of pumpkins for Halloween.

In 1837, the term Jack-O-Lantern appeared in several Irish newspapers as a term for a vegetable lantern. The association with Halloween was documented by 1866. Additionally, in popular culture there’s a connection between pumpkins and the supernatural. Jack-O-Lanterns derive from folklore about a lost soul wandering the earth, searching for his missing head.

Festivities

Annually, Circleville, OH holds a Pumpkin Festival, complete with marching bands, a queen, all sorts of fair foods made with pumpkin, and a prize for the biggest pumpkin. FYI, the largest pumpkin in North American history was grown by a New Hampshire man and tipped the scale at 2,528 pounds. You can find other festivals and pumpkin contests online.

Then there are contests, often including baked goods. More actively, there are games like pumpkin throwing and pumpkin chunking. Chunking involves machines like catapults, trebuchets, ballistas, and air cannons. Some pumpkin chunkers breed and grow pumpkins specifically to improve the pumpkin’s chances of surviving a throw.

Folklore and Fiction

We all know a couple of examples

- Peter, Peter pumpkin eater

Had a wife and couldn’t keep her.

Put her in a pumpkin shell

And there he kept her very well. - Cinderella’s coach for the ball was carved from a pumpkin in many versions

- In some versions of The Legend of Sleepy Hollow, the Headless Horseman has a pumpkin in place of a head

- Pumpkin in the Jar

Overall, in the U.S., pumpkin folklore tends to be light and humorous (though keeping a woman in a gourd root doesn’t sound very nice), often involving the biggest, the fastest, the most fantastic. Pumpkins can talk, or someone hit by a pumpkin thinks he’s dead. Southern American folklore often stems from tall tales told by the descendants of West African slaves in which pumpkins—and pigs—meet magical realism.

In other cultures, pumpkins are often elements of different genres of myths.

- Creation myths

- Laotians believed that all the people of Indo-China came from a pumpkin.

- Magical transformation

- Turning into or giving birth to strange creatures, evil doers, beautiful princesses

- Because it ripens later than most fruits and vegetables, between summer and winter, the pumpkin is often seen as a symbol of change.

- Rebirth

- In many West and Central African cultures, pumpkins stand for rebirth, when a pumpkin grows from a dead mother’s grave.

- In Ukraine, a pumpkin was traditionally given to a suitor to symbolize that there was absolutely no chance of marriage.

Pumpkin History

Some sources, like Wikipedia, claim pumpkins are native to North America (northeastern Mexico and southern U.S). This assertion is based on evidence paleobotanists offer of cultivation as early as 7,500-5,000 BCE. Clearly, the use of pumpkins preceded the cultivation.

The Chinese grew pumpkins in the 6th and 7th centuries. Africa claims to have a pumpkin variety that preceded European or American contact. Pliny the Elder, in first century Rome, described something that seems to have been a pumpkin. Pre-Columbian Peruvians made pottery in the shape of pumpkins—suggesting that pumpkins were both prominent in their gardens and important in their culture. Conclusion: pumpkins were everywhere, very long ago!

Bottom line for writers: surely your plot and/or characters can use some tidbits about pumpkins!