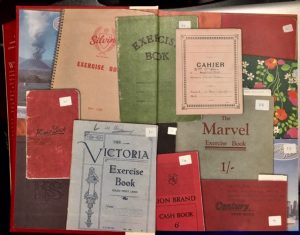

For me—and I venture to say, for most of you reading this blog—the initial exposure to notebooks—books meant to be written in—came with entering school. During the 14th and 15th centuries, notebooks were made by hand, often at home, by folding pieces of paper in half into bundles that were then bound. Binding involved sewing along the fold or punching holes and lacing with twine or other cord. The pages were blank, and any note keeper who wanted lined pages had to make ruled lines across each page. Making and keeping notebooks was so important to effective household, farm, and business management that children learned how to do it in school.

Currently, besides a stitched binding, a buyer can purchase notebooks that are glue-bound, spiral bound, or loose pages in ring binders. People keep notes on everything—food, physical activity, birds cited, blood pressure. . .

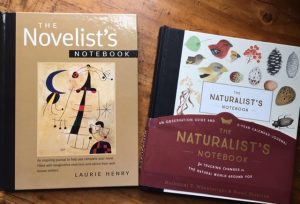

Today, notebooks are almost universally commercially produced. You can find them lined or blank or with printed grids, depending on your intentions. Specialized ones are available for virtually any and all needs. One can shop notebooks for elementary, middle, high school, or college. Additionally, one can find notebooks designed for particular interests.

Specialized notebooks often include related information, advice, etc. The Writer’s Notebook is a good example of this, providing tips and exercises to improve writing and creativity. Of the 207 pages of The Naturalist’s Notebook, the first 95 are pages of how-to. The body of the book is called a 5-year calendar-journal, though it’s set up like a diary.

So, segueing from notebooks to diaries: a diary is a record (originally handwritten) set up for discrete entries arranged by date, reporting on what has happened. Generally, a diary has daily entries. Although it might include anything, a diary is essentially a collection of notes, often brief, focused on “just the facts, ma’am.” A war diary would be a good example: a regularly updated official record of a military unit’s administration and activities, maintained by an officer in the unit.

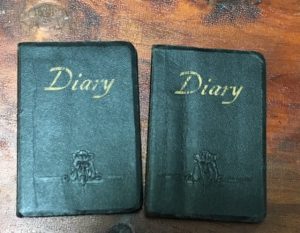

Pre-printed diaries typically allot the same amount of space or number of lines for each day. This forces the diarist to record only the most important events of each day. The diary shown above is set up for one year, with one week on each double-page spread. N.B.: These are a woman’s diaries, and you will see weather notes in the margin of each entry, which is typical of women’s diaries.

One-year diaries can come in any shape or size, though the entry space is often larger than that of multi-year diaries. Typical of diaries are the inserts and write-overs caused by the relatively small amount of space allowed for each day.

To Myself, known today as Meditations, written in Greek by the Roman Emperor Marcus Aurelius in the second half of the 2nd century CE might be the earliest recorded writing displaying many aspects of a diary. The earliest surviving diary that most resembles a modern diary was that of the Moroccan mathematician and scholar Ibn al-Banna’ al-Marrakushi in the 11th century. Needless to say, these were not pre-printed!

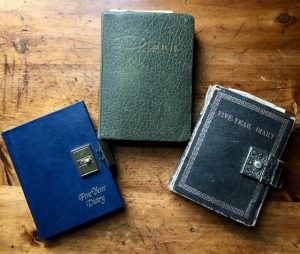

At one point, five-year diaries were very popular. They range in size from 2” x 3” up to 8.5’ x 11” and are still for sale today, priced from $5.59 to $72.00, though the price is not necessarily related to size. The major advantage of a five-year diary, in my opinion, is that it allows easy tracking of events (visits from relatives, weather, flower blooms) across years and seasons. The major disadvantage is the (usually) severely circumscribed space for each entry.

Today one can have a paper diary and/or a digital diary. Digital diaries are often tailored towards shorter-form, in-the-moment writing, similar to what might be posted on social media, but they avoid character limits that have the same effect as the space restrictions noted above.

In its original (French) meaning, the word journal (from the Latin diurnis or diurnalis)refers to a daily record of activities, but the term has evolved to mean any record, regardless of time elapsed between entries. More importantly, it is a record of significant experiences, as well as documenting thoughts, feelings, reflections, emotions, problems, and self-evaluations. In short, a journal is much more personal than a diary. Per Robert Gottlieb, journals have no deliberate shape, they simply accrete.

In writers’ terms, a diary is a fly-on-the-wall POV; a journal is a first person POV, showing everything through the eyes and heart of the writer.

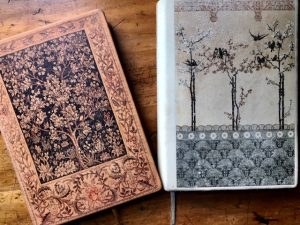

If you want to buy a journal, you are not likely to find books labeled “Journal.” Instead, you buy a blank book. Your first decision is totally blank or lined. It’s a very personal decision. For an artist, this would be totally blank, a sketchbook. But some journal writers also want a totally blank page,feeling freer—unconfined, not squished between lines. Others—somehow more restricted?—prefer lines, perhaps to keep them focused, perhaps to keep their words legible.

Journals can be broad ranging or focused—for example, dream journals, travel journals, gardening journals. In my experience, the more broad ranging, the more likely the writer will choose an aesthetically pleasing blank book.

For the most part, both diaries and journals are presumed to be personal, shared with no one or only a select few. But many of both have been published. Online, international lists of published journals and diaries are readily available.

An exception to the presumption of privacy, The Diary of Anais Nin was her own publication.

But many others are published posthumously.

Agatha Christie’s Secret Notebooks—numerous, informal, and not terribly organized—have been perused and edited by John Curran. He quotes lavishly from the originals but also comments and relates the notebook entries to Christie’s published works.

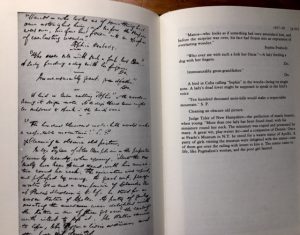

Among published diaries, notebooks, and journals, one of my favorites is Hawthorne’s Lost Notebook 1835-1841. I love this book because it has reproductions of the original hand-written notes side-by-side with readable printed versions of his words.

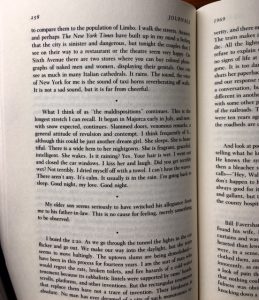

Another favorite is The Journals of John Cheever. Cheever wrote his inner life, day after day, year after year. His writings span a period from the early 1940s to a few days before his death on June 18, 1982, encompassing some three to four million words. The original journals are small, loose-leaf note books, approximately one per year, usually typed but sometimes written out in longhand, undated. The published version of his journals is, necessarily, a selection. Entries are identified by year, and each is reprinted in its entirety.

This printed version of his journals doesn’t draw punches, even when he made negative comments about his children or himself.

And now I would draw your attention to the similarities between the Hawthorne notebook entry and the Cheever journal entries. They are both open-ended and extremely personal.

Bottom line for writers: a rose by any other name! Call it a notebook, a diary, or a journal, record your days.

This is such a wonderful article, I haven’t read like this before. Clearly explains about diary and its uses. Thanks for sharing great content.