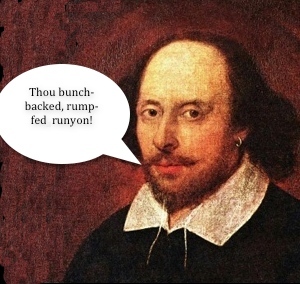

Not body language—facial expressions, gestures, movement, etc. Rather, body parts used in clichés and idioms that mean more than the words. Keep your nose to the grindstone or Have a silver tongue.

Linguists have noticed that English is not the only language with idioms full of body parts. Czech, Korean, Malay, Pashto, Turkish, Igbo, and Vietnamese (just to name a few) are full of body part phrases that mean more than the literal sum of their parts. It seems, no matter what language you speak, your brain reaches for parts of your own body when looking for interesting ways to express yourself.

So, head to toe, here are examples.

Head

- Hard-headed

- Soft in the head

- Bang your head against a brick wall

- Keeping your head above water

- Able to do something standing on your head

- Keep your head down

- Hold your head high

- Bite someone’s head off

- Head in the clouds

- Head in the sand

- Bring something to a head

- Can’t make heads or tails out of something

- Drum something into someone’s head

- Head to toe

- Keep your head in the game

- Fall head over heels in love

- Get a head start on something

- Get someone or something out of one’s head

- Give someone a head’s start

- Go over someone’s head

- Have a good head on your shoulders

- Head someone or something off

- Hit the nail on the head

- In over your head

- Lose your head

- Keep your head

- Off your head

- Scratching your head over something

Brain

- Right brain/left brain

- Brain storm

- Brain fart

- Brain buzz

- Brain freeze

- Brain dead

- Braining (to hit someone on the head)

Neck

- A pain in the neck

- Stick your neck out

- Neck and neck

- Breathe down your neck

- Dead from the neck up

- Up to your neck

- Neck of the woods

- Millstone round your neck

- (Competitors are) neck and neck

- To save your neck

- Risking your neck

- Wring his or her neck

- Rubber necking

Shoulders

- A chip on your shoulder

- Come straight from the shoulder

- Give someone the cold shoulder

- Put your shoulder to the wheel

- A shoulder to cry on

- Stand shoulder to shoulder

- Shoulder a burden

Arm

- Arm of the law

- Cost an arm and a leg

- Give your right arm

- Up in arms

- (Keep) at arm’s length

- Strong arm someone

Hands

- Give a hand

- At hand

- Out of hand

- Bite the hand that feeds you

- Change hands

- First hand

- Hands down

- Have a hand in

- A firm hand

- Hand something over

- Hand in glove

- Heavy handed

- Hand holding

- In your hand

- Lend a hand

- Out of your hands

- Wash your hands of

- Get your hands dirty

- Hands full

- Hands tied

- Live from hand to mouth

- All hands on deck

Chest

- Something will put hair on your chest

- Get something off your chest

- Keep your cards close to your chest

- Chest thumping

Spine

- Spineless

- (Send) a shiver down someone’s spine

- Spine-tingling

- Spine of steel

Heart

- Change of heart

- Heart of gold

- Eat your heart out

- Know/learn something by heart

- After your own heart

- Cross your heart

- Lose heart

- Follow your heart

- Heart skips/misses a beat

- Take heart

- Follow your heart

- Break your heart

- Have your heart set on/against something

- Heartbeat away

- My heart bleeds

- Bleeding heart

- Heart of stone

- Soft-hearted

- Young at heart

- Wear your heart on your sleeve

- Big-hearted

- A heavy heart

- From the bottom of your heart

- Get to the heart of the matter

- Be halfhearted about something

- Have a heart-to-heart talk

- Heart in the right place

- Pour your heart out

Guts

- Gut feeling /reaction

- Gut punch

- Beer gut

- Blood and guts

- Bust a gut

- Go with (one’s) gut

- Gut feeling /instinct

- Gut it out

- Gutted

- Gut-wrenching

- Hate someone’s guts

- Have someone’s guts for garters

- Have the guts (to do something)

- No guts, no glory

- Puke (one’s) guts out

- Slog/sweat/work your guts out

- Spill your guts

- Split a gut

Leg

- Not have a leg to stand on

- On one’s last legs

- On the last leg (of a journey)

- Pull (someone’s) leg

- Put your pants on one leg at a time

- Have/find your sea legs

- Get/give a leg up

- Break a leg (theater)

- To have hollow legs

- To leg it

- To talk the hind leg off a donkey

- To pull someone’s leg

Knees

- Bee’s knees

- On one’s knees / bring to one’s knees

- Knee-high to a grasshopper

- Weak in the knees

- Take a knee (football)

Feet

- Cold feet

- Foot in the door

- Have two left feet

- Get off on the wrong foot

- Have itchy feet

- Put your foot down

- Feet on the ground

- Foot the bill

- Get back on your feet

- Feet of clay

- Get your feet wet

- Swept off your feet

- Best foot forward

- Have a lead foot

- One foot in the grave

- Bound hand and foot

- Dead on my feet

- Foot in both camps

- Jump in feet first

- On the back foot

Heels

- Achilles heel

- Bring someone to heel

- Cool one’s heels

- Dig in your heels

- Be a heel

Toes

- Dip one’s toes in (the water)

- Keep someone on their toes

- Step/tread on someone’s toes

- Toe the mark

Bottom Line: When words about body parts don’t literally mean what they say, they can be used in an infinite number of ways.