In 2012 I received a letter from a man I had dated in graduate school. I had not seen or heard from him in decades. He told me that he owned a small villa in northern Italy which he rented during the season but spent time there himself in spring and fall. While there in October, he found a Kindle some renter had left behind. He browsed the library, didn’t recognize titles or authors, but read Dark Harbor. He liked it. He decided to check out the authors. As soon as he saw my website, he recognized me and decided to get in touch.

That whole circumstance was so flattering that I told numerous friends and fellow-writers. Who knew my book would make it to Italy? I mention it now because it’s happened again! Only this time with a twist.

His letter began, “Dear Ms. Lawry—I‘ve just competed a most pleasurable reading of your novel Dark Harbor. What a cast of suspects! My primary feeling at the end is happiness that the foul victim got what he had coming….[sic]” Then came the twist: “But the principal reason I am writing concerns an unusual document of which you’ll find a copy enclosed.”

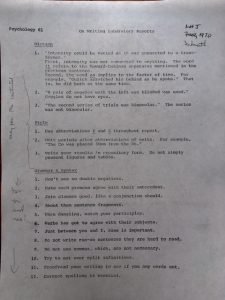

“This turned up on my desk a couple of weeks ago, mixed in with unrelated papers, and caused me to think of the co-author of your book, who composed this page very nearly fifty years ago. I was a student of Professor Gulick’s at Dartmouth, lo these many years ago, and as you will see from this page, he was not only an inspirational lecturer in the realm of sensory psychology but also a droll and vigorous defender of the English language!”

In case you can’t read the photo, I will copy what Gulick said about grammar and syntax in writing laboratory reports.

Grammar & Syntax

1. Don’t use no double negatives.

2. Make each pronoun agree with their antecedent.

3. Join clauses good, like a conjunction should.

4. About them sentence fragments.

5. When dangling, watch your participles.

6. Verbs got to agree with their subjects.

7. Just between you and I, case is important.

8. Do not write run-on sentences they are hard to read.

9. Do not use commas, which, are not necessary.

10. Try not to ever split infinitives.

11. Proofread your writing to see if you any words out.

12. Correct spelling is esential.

Later in the letter: “I looked in vain for an e-mail address for Professor Gulick… And in [reading Dark Harbor] I discovered your website and blog and your physical address… Hence this letter. I wonder if you would be so kind as to pass this along to Professor Gulick? I hope he might smile over the notion that his little document has endured for so long as both a pedagogical tool and source of chuckles.”

Of course I did so. A subsequent email from the letter writer complimented Tiger Heart and asked, “Dare I hope there will be a sequel?” My response was “…thank you again for the compliments on our mysteries. I doubt there will be a sequel. Lawry is approaching his 91st birthday and no longer owns a boat (the prototype for Nora’s boat). Although he started teaching me to sail in 1995, he was the expert. I’d never sail alone and know no one else with a sailboat at this time. I’ve toyed with the idea of continuing with the cast of characters but making it less water-related. We shall see.”

This exchange has made me think a lot about language and its evolution. My coauthor had several language preferences that seemed to me old fashioned, among them his preference for ’til over till, and expertness over expertise. I strongly prefer to set priorities rather than prioritize. We both share an abhorrence of the word “data” coupled with a singular verb, as does the letter writer. His sons, both software engineers, “…persist in using the construction ‘data is’…..[sic] I suppose it is so much in use these days as a collective noun more or less equivalent to ‘information’ that this is a battle which I’m not going to win!”

And that brings me to Bill Bryson.

I urge every writer to read Bill Bryson’s book Mother Tongue: English and how it got that way. Not surprisingly, it’s about the evolution of English. At some point he writes that people believe that the correct ways to speak, write, and spell are whatever was being taught at the time they finished formal schooling. The language continues to evolve—and every writer should take care that the language is true to the time and place of the story.