Turkey breeders domesticated farmyard turkeys from a species actually called the Wild Turkey (Meleagris gallopavo), native to the eastern and southwestern states and parts of Mexico. Last week’s blog explores turkey origins, early domestication, and return to the U.S. from Europe with colonists.

The Modern Turkey

Domestic stock returned from Europe was eventually crossbred with the wild turkeys of North America. Today, there are six common standard domestic varieties in the United States:

- Bronze

- Black

- Narraganset

- Bourbon Red

- Slate

- White Holland

Although wild and domestic turkeys are genetically the same species, that’s about where the similarity ends.

The domestic turkey lost its ability to fly well through selective breeding that created heavier, broad-breasted birds. The shorter legs of the domestic turkey also mean it can’t run as well as its wild cousin.

Generations of farmers have bred domesticated turkeys to have more breast meat, meatier thighs, and white feathers. (White feathers don’t leave the dark pigmentation after plucking.) Most of the turkey we eat is from the Broad Breasted White breed.

Americans consume about 736 million pounds of turkey each Thanksgiving. In 2022, Americans collectively spent approximately $1.1 billion on Thanksgiving turkeys.

One fifth of America’s annual turkey consumption is on the Thanksgiving dinner table.

What About Turkeys Off the Thanksgiving Platter?

Some reports say Americans consume an average of 18 pounds of turkey meat per capita each year. Other estimates suggest it’s 13.6 pounds per person. In any case, it’s more than anyone consumes at a single meal, even Thanksgiving.

While Americans prefer the white meat of turkeys, most of the rest of the world prefers the dark meat.

Avian myologists (bird muscle scientists) refer to dark meat as “red muscle.” Animals use red muscle for sustained activity—chiefly walking, in the case of a turkey. The dark color comes from a chemical compound in the muscle called myoglobin, which plays a key role in oxygen transport. White muscle, in contrast, is suitable only for short bursts of activity such as, for turkeys, flying. That’s why the turkey’s leg meat and thigh meat are dark, and its breast meat (which makes up the primary flight muscles) is white. Other more “flighty” birds, such as ducks and geese, have red muscle (and dark meat) throughout.

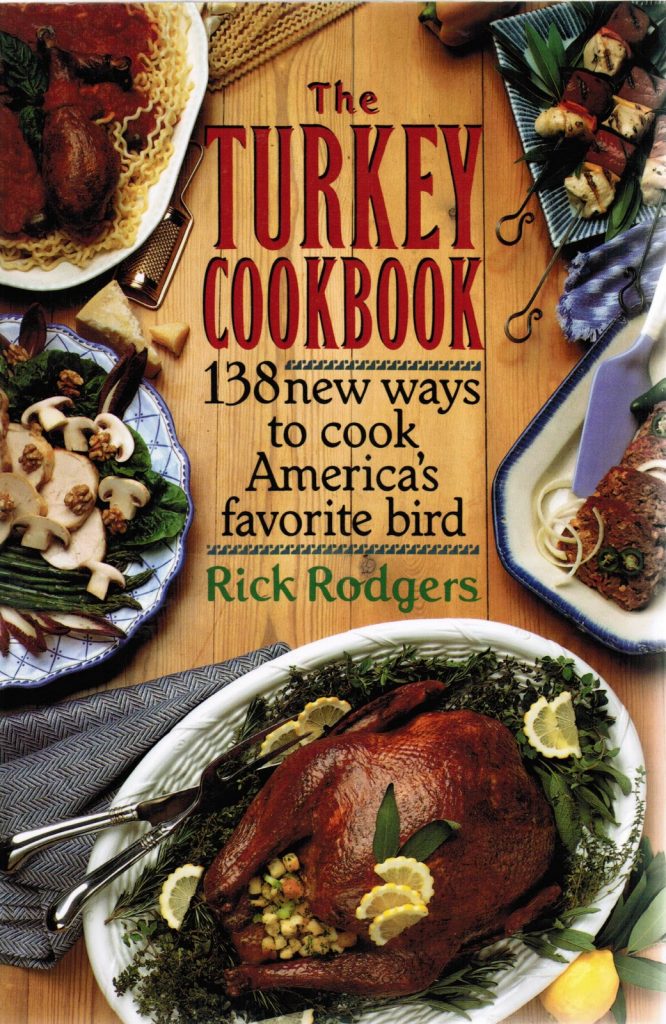

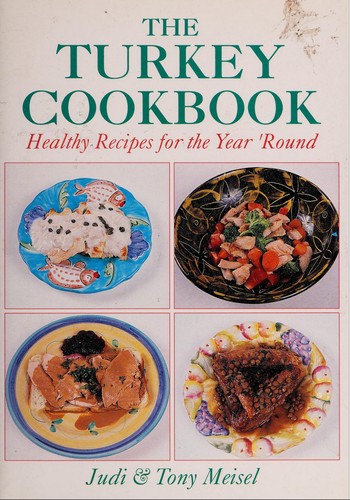

Creative chefs have written whole cookbooks about turkey.

by Rick Rodgers

by Judi and Tony Meisel

by Chef Jumoke Jackson

As with other cookbooks, you can find recipes for appetizers, beverages, soups, breads, salads, side dishes, sandwiches, burgers, and many uses for leftovers.

Facts About Turkeys Off the Table

Male turkeys are sometimes called “gobblers,” after the “gobble” call they make. Alternatively, they are called “toms.” Females are called “hens.”

Many factors impact a tom turkey’s impulse to gobble. The presence of other male turkeys or of female turkeys, the weather, the time of year, and a turkey’s age all influence when and how loudly a tom turkey gobbles.

Hens make a clucking sound. Other turkey sounds include “purrs,” “yelps,” “cutts,” “cackles,” “hoots,” and “kee-kees.”

Adult gobblers weigh between 16 and 22 pounds. They have a beard of modified feathers on their chests that reaches seven inches or more long and sharp spurs on their legs for fighting.

Hens are smaller, weighing around 8 to 12 pounds. They have no beard or spurs.

Both genders have a snood (a dangly appendage on the face) and a wattle (the red, fleshy thing that hangs from a turkey’s neck). However, they only have a few feathers on the head.

Snood length is an indicator of a male turkey’s health. When males challenge each other, scientists can use snood length to predict the winner. In addition, a 1997 study in the Journal of Avian Biology found that female turkeys prefer males with long snoods.

Tom turkeys also have caruncles, visible bumps on their heads. The larger the caruncles, the more testosterone a tom has.

Turkey hens live together in flocks (called rafters) with their female young. These rafters can have 50 or more birds!

Male turkeys form their own flocks, sometimes further separated by age. At mating time, a group of related male turkeys will band together to court females. However, only one member of the group gets to mate.

Commercial poultry farms today artificially inseminate turkey eggs. Generations of selectively breeding for larger breasts has created birds too large and heavy to mate naturally.

When a hen is ready to make little turkeys, she’ll lay one egg per day, over a period of about two weeks until she has a clutch of 10 to 12 eggs. Then, the eggs incubate for about one month before hatching.

Baby turkeys (poults) eat primarily berries, seeds, and insects. An adult’s more varied diet can include acorns and even small reptiles.

A clever observer can determine a turkey’s gender from its droppings. Males produce long, thin, spiral-shaped poop. Females’ poop clumps more and looks like the letter J.

Early farmers kept turkeys on small farms not just for their meat but also because they ate large numbers of insects and so were a great source of pest control.

One of the difficulties of raising turkeys stems from their curiosity. Without sturdy and cleverly built pens, turkeys will get out of their enclosures and wander off to explore the neighborhood. Also, they tend to get into places they can’t get out of, such as nearby buildings and the pens of other animals. In particular, turkeys commonly get their heads caught in fences!

A flock of wild turkeys has caused problems at NASA’s Ames Research Center in Mountain View, California. The curious and territorial birds are big enough to deter pedestrians, stop traffic, and even halt aircraft.

Adults must teach their young to eat from special feeders and waterers, just like other baby animals.

Turkeys like to roost high up in trees where they are safe from predators and can see any danger coming. They are not always graceful when descending, often crashing from branch to branch on their way to the ground.

Turkeys have approximately 3,500 feathers at maturity. If you’re particularly industrious, you can use these feathers, along with chicken feathers, to make feather-tick bedding. It’s not nearly so light and comfy as down!

Wild turkeys swim very well. They can flatten their feathers for a stream-lined effect, steer with their tails, and kick with their powerful legs.

Turkey skins are tanned and used to make items like cowboy boots, belts, and other accessories.

The dance called the Turkey Trot was named for the short, jerky steps a turkey makes. It became very popular following its introduction in a San Francisco nightclub in 1910. The movements were so “outlandish” that authorities used to arrest people for Turkey Trotting in public, and Pope Pius X begged his flock not to follow the new dance craze.

Before modern transportation, farmers in the British Isles put leather shoes on turkeys and walked them to market.

The 57th Annual Tremont Turkey Festival was held June 9-11, 2023. The festival features footraces, bed races, horseshoes, music, a parade, food, food, food, and more.

Bottom line: (Some people think) turkeys are kind of cool.