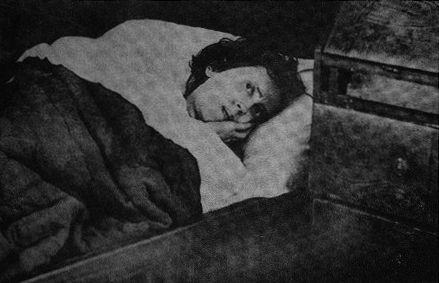

Is that even a thing? I asked myself that question after the night I slept more than eleven hours. First, I looked up what’s typical.

Recommended Sleep by Age

The following table is from the CDC.

| Age Group | Age Range | Recommended Hours of Sleep |

| Infant | 4-12 months | 12-16 hours (including naps) |

| Toddler | 1-2 years | 11-14 hours (including naps) |

| Preschool | 3-5 years | 10-13 hours (including naps) |

| School-Age | 6-12 years | 9-12 hours |

| Teen | 13-18 years | 8-10 hours |

| Adult | 18-60 years | 7 or more |

| 61-64 years | 7-9 hours | |

| 65+ years | 7-8 hours |

So, either I’m back to my middle school years, or I’m beyond the pale. No doubt the latter, but is that a bad thing?

Why Do People Sleep Too Much?

For people who suffer from hypersomnia, oversleeping is actually a medical disorder. The condition causes people to suffer from extreme

sleepiness throughout the day, which is not usually relieved by napping. It also causes them to sleep for unusually long periods of time at night. Many people with hypersomnia experience symptoms of anxiety, low energy, and memory problems as a result of their almost constant need for sleep.

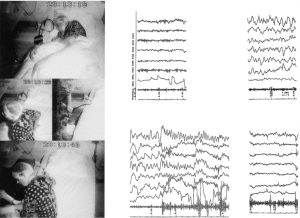

Obstructive sleep apnea occurs when something blocks part or all of your upper airway while you sleep. Your diaphragm and chest muscles have to work harder to open your airway and pull air into your lungs. Your breath can become very shallow, or you may even stop breathing briefly. You usually start to breathe again with a loud gasp, snort, or body jerk. You may not sleep well, but you probably won’t even know that it’s happening. This condition can also lower the flow of oxygen to your organs and cause uneven heart rhythms.

Not everyone who oversleeps has a medical sleep disorder. Other possible causes of oversleeping include:

- Alcohol

- Prescription medications

- Jet lag

- Illness, such as a cold or flu

- Extreme athletic exertion

- Depression

Besides the conditions mentioned above, too much sleep — as well as not enough sleep — raises the risk of: heart disease, diabetes, depression, and obesity in adults age 45 and older. Any of these can carry an increased risk of death.

Sleeping Preference

And then there are people who simply want to sleep a lot. Individual sleep needs vary as widely as individual dietary needs, but “anything worth doing is worth overdoing” (as Mick Jagger, Ayn Rand, or possibly G. K. Chesterton famously said).

If long-term risks are too distant to motivate stopping, consider this: if you sleep more than you need to, you’re probably going to wake up from a later sleep cycle, meaning you’ll feel groggy and tired even though you’ve slept more. Research bears out the connection between too much sleep and too little energy.

According to Harvard Health, it appears that any significant deviation from normal sleep patterns can upset the body’s rhythms and increase daytime fatigue. The best solution is to figure out how many hours of sleep are right for you and then stick with it — even on weekends, vacations, and holidays.

How to Manage and Treat Chronic Oversleeping

- Stop trying to “collect” sleep hours ahead of time.

- Establish consistent sleep and wake times.

- Have a regular exercise routine.

- Avoid caffeine eight hours before bed and excessive alcohol completely, if possible.

- Skip long naps, if possible.

- Seek testing for medical causes like sleep apnea, narcolepsy, depression, Prader-Willi syndrome, Kleine-Levin syndrome, or hypothyroidism.

But What If It’s Only Occasional?

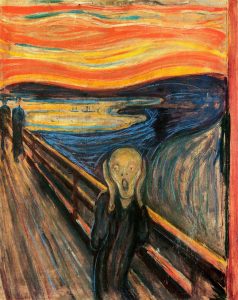

According to the Cleveland Clinic, when you’re sleep drunk, your brain doesn’t make the transition to wakefulness. Your conscious mind isn’t fully awake, but your body can get up, walk, and talk. “People who have confusional arousal might act confused or have trouble speaking,” says Dr. Martinez-Gonzalez. “They might appear to be drunk, but they’re not.”

The CDC discusses sleep inertia. It is a temporary disorientation and decline in performance and/or mood after awakening from sleep.

People with sleep inertia can show slower reaction time, poorer short-term memory, and slower speeds of thinking, reasoning, remembering, and learning.

Bottom Line: Inviting as a warm bed can be on a winter night, as comfortable as it feels during a pounding rain, as luxurious as it can feel to just not get up, consider the price you may pay.