A couple of weeks ago, I blogged about makeup for men. Researching that topic took me deep into the worldwide history of cosmetics. But discussions of cosmetics for African Americans or Native Americans were glaringly absent.

There are many reasons for this, ranging from forced relocations disrupting a community’s access to materials traditionally used for beautification, to societal beauty expectations, to cultural practices, even to the way film development parameters affect the way darker skin tones appear in photos and movies. The history of makeup use in darker-skinned communities in America also reflects the segregation and discrimination non-white people have faced. Cosmetics marketed to lighten or bleach skin, hair care products advertised to change texture, and a variety of treatments purported to change one’s racial appearance have been on the market for as long as the market has existed. The idea that one must mimic European ideals of beauty to be attractive is slowly changing.

Native American Cosmetics

In researching Native Americans, I found little that was specified for beautification, but many practices that would improve appearance. Across the entire North American continent, many different environments present very different challenges and materials for skin care and beautification. A Miccosukee person living in the heat and humidity of Florida would have a very different beauty regimen than a nomadic Assiniboine person living on the northern Great Plains. Better Nutrition identifies these 5 specific sources of health and beauty for Native Americans commonly used in the Mojave Desert. The article does not specify which tribe used these methods, but the author mentions researching in Sedona Arizona, where the Yavapai, Tonto Apache, Hopi, and Navajo lived at various times in history. (Bolding added.)

“Desert-dwelling Native Americans used aloe vera gel to expedite wound healing, soothe sunburn, and hydrate skin. Aloe is antimicrobial, antibacterial, antifungal, anti-inflammatory, and it contains antioxidants. Aloe also has phytosterols that help soothe itches and irritation. The bioactive compounds in the plant are rich in vitamins A, B, C, D, and E as well as magnesium, potassium, and zinc that aid healing.

“Agave nectar is antimicrobial and was mixed with salt by Native Americans to heal skin conditions. Agave’s sugars soften skin and lock moisture inside hair. These sugars form complex bonds with internal proteins to add strength, resiliency, and elasticity to skin and hair.

“Native Americans ate the prickly pear and used oil from the fruit’s seeds to help strengthen skin and hair. The oil contains twice as many proteins and fatty acids as argan oil, and is rich in vitamin E, making it an excellent remedy for damaged or mature skin and dry hair. Linoleic and oleic fatty acids help moisturize and restore skin’s elasticity. The vitamin K in prickly pear helps to brighten dark spots and undereye dark circles.

“Native Americans discovered that juniper berries produce a stimulating, astringent, and detoxifying oil. They used it to remove impurities. Today, juniper oil is a key ingredient in detox skin products. It can balance oily skin and open blocked pores and keep them clear. Juniper improves circulation and reduces swelling, making it an ideal ingredient in massage oil.

“Native Americans used the juice from the yucca root to make soap and shampoo because of its ability to lather. Since it’s packed with vitamin C and other antioxidants that soothe and nourish the skin and scalp, they also used it to treat ailments from acne to hair loss. Yucca is also anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, and detoxifying.”

Many ingredients in modern beauty products were first used by Native Americans. In areas where maize was a prominent crop, people ground corn to use as a skin cleanser. It was often rubbed on to the skin to remove impurities from the body, sometimes for ceremonial purposes.

By “cosmetics” one usually means preparations intended to make the wearer more attractive, used as part of one’s regular toilet. Such cosmetics are typically removed daily.

Although not cosmetics in the above sense, the oldest materials used in Native American face paint were derived from animal, vegetable and mineral sources, with earth or mineral paint being the most common. White and yellow paint was obtained from white and yellow clays along river beds, and buffalo gallstones produced a different kind of yellow.

A growing number of cosmetic and skincare brands owned by Native people make use of traditional materials. Cosmopolitan recently published an article highlighting makeup brands owned and run by Indigenous Americans, including Prados Beauty, Cheekbone Beauty, Ah-Shí Beauty, and Sḵwálwen Botanicals. Huffington Post wrote about how some of these brands are using marketing and product design to break down harmful stereotypes and educate consumers about distinctions among the many, varied tribal cultures.

Black Cosmetics

By comparison, searching for African American/Black cosmetics turns up a long history of a population underserved by commercial cosmetic companies.

A black man born during slavery, Anthony Overton, opened the Overton Hygienic Manufacturing Co. in Kansas in 1898, to sell baking powder and other products to drug and grocery stores. Recognizing the absence of cosmetics in skin tones for women of color prompted his foray into makeup.

In the early 1900s, large department stores did not stock products for people of color, so Overton developed a network of salespeople who visited small stores with samples. People could also send for his products by mail.

Sales of Overton’s “high-brown” face powder boomed in the United States and countries like Egypt and Liberia. Overton Hygienic relocated to Chicago’s South State Street in 1911, and the next year went on to manufacture more than 50 products, including hair creams and eye makeup. The face powder expanded from “high brown” to include darker and lighter shades, such as “nut-brown,” “olive-tone,” “brunette,” and “flesh-pink.” Importantly, Overton (who had a chemistry degree) insured that his makeup was safe, unlike many products then on the market.

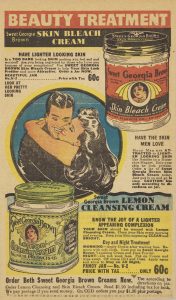

In 1926, Morton Neumann, a Hungarian American also a chemist who grew up in Chicago, established Valmor Products Co., which largely targeted black customers. A big seller was Sweet Georgia Brown face powder, then available for 60 cents in colors like “tantalizing dark brown,” “aristocratic brown,” “sun-tan,” and “teezum [tease ’em] red.” Sweet Georgia Brown also widely marketed skin bleaching creams, reflecting the continuing trend trend of equating lighter complexions with beauty and desirability.

What does it tell you that one ad for the face powder promised a “lighter appearance in 10 seconds” and pointed out that the powder “is specially made to give tan and dark complexions the BRIGHTER attractive beauty that everybody admires.”

Unfortunately, skin bleaching has not gone away. Many companies still produce creams, powders, and even drugs that cover skin, chemically bleach skin, or disrupt melanin production, often with painful and dangerous side effects.

In 1923, two white, Jewish chemists — Morris Shapiro and Joseph Menke — opened Keystone Laboratories in Memphis. They split up, and Shapiro launched Lucky Heart Laboratories in 1935. Lucky Heart products were sold only by representatives, often community members, to show the cosmetics “to friends, neighbors, people you know at work, church or in social groups.”

“Both Keystone and Lucky Heart are still in business today. They primarily sell hair and skincare products, with some relics of the past, such as Lucky Heart’s beauty bleaching cream. Lucky once offered makeup products like tint cream and a Color-Keyed Cosmetics line. However, another Memphis cosmetics business, the Hi-Hat Company, prided itself on offering “smart shades for every complexion.” Hi-Hat’s Jockey Club face powder came in hues such as ‘Harlem tan,’ ‘Spanish rose,’ ‘chocolate brown,’ and ‘copper bronze.’”

(racked.com)

In the 1960s, mainstream brands like Maybelline and Avon got into the act. During the five years that ended the 1960s, a half-dozen cosmetics lines for black women debuted. One of them, Flori Roberts, bills itself as the first such line that department stores carried.

In earlier years, women of color mixed shades to make the right foundation shade for their skin. But that didn’t address issues of oil or silicone.

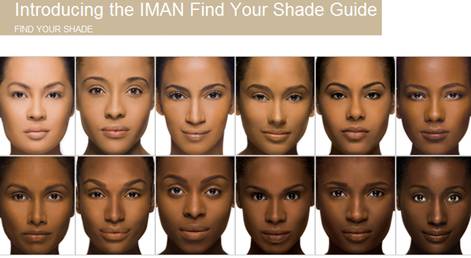

In 1994, Somali supermodel Iman Abdulmajid started IMAN Cosmetics, to serve women whom other makeup manufacturers had overlooked — blacks, Latinas, Asians. The basic premise was/is that skin tones overlap, so cosmetics companies shouldn’t target one ethnic group.

Today, women of color have more options when looking for cosmetics to match or complement their skin tones. Mainstream brands such as AJ Crimson, B.L.A.C Minerals, Plain Jane Beauty, M.A.C., Bobbi Brown, Cake Cosmetics, Makeup Forever, Nars, Lancôme, and others have widened their color palettes in foundation, eyeshadow, lipstick, liners, and contouring. Ulta Beauty, one of the largest makeup retailers in the country, has an entire section of Black-owned brands of skincare, hair care, and makeup products.

Bottom Line: Where there’s a will, there’s a way. And today women (and men) have more makeup and cosmetic options than ever before.