The subtle, quiet displays of merchants in the area may have hinted at it, but just in case you didn’t notice: Christmas is coming! Yes, I know, it’s easy to overlook the slight adjustments in advertising décor and to miss the odd carol or two playing on radio stations. Santa Claus will be coming to town in approximately twenty days (depending on when you read this).

But did you know that St. Nicholas is also coming? And that Father Christmas is coming? Grandfather Frost will be here with his granddaughter the Snow Maiden. If you’re very lucky, you might even get a glimpse of Befana, Joulupukki the Yule Goat, Amu Nowruz, or Olentzero. The evolution of modern Christmas customs, including Santa Claus, has been discussed on this blog before.

If you’re very lucky and have highly refined literary tastes, you may catch a glimpse of the Hogfather.

Krampus, Belsnickel, Pere Fouettard, Knecht Ruprecht, the Yule Lads, and other Companions will probably be coming to town as well, but you should probably hope you don’t run into them.

But why should you care about all these visitors wandering about your town? (Besides the tendency to trespass and child beating, of course?) If society is reflected in its myths, then the writer can illustrate society by mentioning the myths.

Real World Gift-Givers

As discussed before, humans tend to follow the sun. When it goes away, we tend to get a little anxious and want it to come back. The tendency to mark the solstices appears in almost every part of the world that sees the effects of axial rotation. Giving gifts is a common theme at this time of year, often contrasted with giving coal or beatings to the deserving.

Writing teachers are always telling us to “show, not tell.” Referring to a culturally specific Santa-esque figure is a great way to show where and when a story is set. Consider some of these holiday figures with a habit of giving sweets, money, and gifts to deserving believers. Many of them are accompanied by a darker foil who comes to punish those who have been “naughty” during the preceding year.

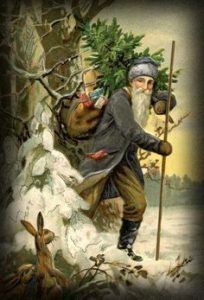

Father Christmas

Today, Father Christmas is often depicted as simply the English version of Santa Claus. Look back a few hundred years, however, and you’ll see a very different figure. Oliver Cromwell’s puritan government cancelled Christmas during the English Civil War; the public brought it back during the Restoration of 1660. At that time, Father Christmas was the personification of Medieval customs of feasting and making merry to celebrate Yule. The evolution of Father Christmas since that time follows the changes in common Christmas celebrations in England.

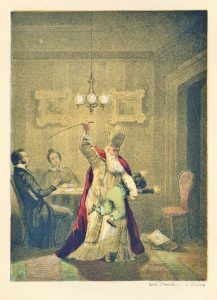

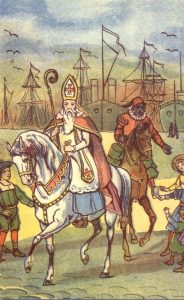

Sinterklaas/ Saint Nicholas

Saint Nicholas Day is almost upon us! Dutch children will leave their shoes on the doorstep or by the fire so that Sinterklaas can fill them with candy and toys. If children have been naughty, Sinterklaas’s assistant Zwarte Piet beats them with a stick or throws them into his sack and sends them to Spain. The historical Saint Nicholas was the Bishop of Myra (in modern Turkey) and patron saint of children and travelers. He arrives by steamboat and parades through town on a white horse, wearing his traditional bishop’s attire, accompanied by his assistants. Sinterklaas carries a huge, red book with a list of all the naughty and nice children in the area. The modern American Santa Claus owes much of his current fashionable ensemble to Sinterklaas.

Zwarte Piet, Black Peter, is a very controversial figure in modern Sinterklaas festivities and worthy of a separate discussion all his own.

Three Kings or Three Wise Men

In many traditionally Catholic countries, gifts are brought by three figures: the Wise Men from the East mentioned in the Gospel of Matthew. On their way to bringing gold, frankincense, and myrrh to Baby Jesus, the Wise Men take a break to deliver gifts to good children in Venezuela, Spain, the Philippines, and many other countries. Very few specifics are actually given in the Bible, but traditions have filled in plenty of details. Kaspar, Melchior, and Balthazar may have come from Persia, Arabia, Pakistan, India, China, Tibet, Mongolia, Armenia, or Babylon, depending on local custom. Gifts are often given to children on January 4th, the Feast of the Epiphany, instead of December 25th.

Amu Nowruz

Uncle Nowruz gives gifts to children at the Iranian New Year, which occurs at the Spring Equinox rather than the Winter Solstice. He spends the year travelling the world with Haji Nowruz, a soot-covered minstrel. While Haji Nowruz dances and sings, Amu Nowruz gives coins and candy to children.

Seven Lucky Gods (Shichifukujin)

Ebisu, Daikokuten, Bishamonten, Benzaiten, Juroujin, Hotei, Fukurokuju bring their treasure ship Takarabune to Japan on January 2, the beginning of the New Year. Like the early Father Christmas, the Seven Lucky Gods bring good cheer and prosperity to everyone. Those who sleep with a picture of the Shichifukujin under their pillow will have good fortune in the coming year.

Fictional Gift-Givers

Pretty much any setting for a story on Earth has a celebration of midwinter or year’s beginning, complete with a figure who rewards or punishes believers according to their behavior the previous year. But what if the story doesn’t take place on Earth?

Once again, those who have gone before can show us how it’s done. Articles on io9, tv.tropes, and Goodreads show just how commonly a winter festival centered around gifts and the return of light occur in other universes. Tallying the previous year’s sins and distributing charity are common themes.

For a writer, midwinter festivals offer a chance to showcase family bonds, strengthen relationships, demonstrate local superstitions, or just have characters party.

Moș Gerilă

Honestly, I wasn’t sure whether to include Moș Gerilă as a real gift-giving figure or a fantasy. This “Old Man Frost” was created by the Romanian Communist Party in 1947 as part of an attempt to shift Christmas celebrations from the Orthodox Church and the private family to the state. Moș Gerilă was portrayed as a handsome, bare-chested, young man who brought gifts to factory workers. All celebrations were held on December 30th, the national Day of the Republic. Festivities with decorated trees and patriotic music were held in public spaces, and Moș Gerilă would come bearing gifts of nuts and sweets from the Communist Party to well-behaved children. The fate of badly-behaved children is not clear, but I would imagine a gulag was involved. After the fall of the Romanian Communist Party in 1990, Moș Gerilă disappeared and Moș Crăciun (Father Christmas, similar to the Russian Grandfather Snow) took his place.

Xmas

Futurama, set in the year 3000, has an Xmas episode each season. Celebrants decorate a palm tree with lights and barricade themselves indoors. Santa Claus has been replaced by a robot with a programming error. He judges everyone to be naughty and attempts to exterminate everyone on Earth every year. Kevlar vests and body armor are common gifts.

Life Day

According to fan gossip, George Lucas attempted to find and destroy every copy of The Star Wars Holiday Special after it aired for the only time in 1978. Life Day is a Wookie holiday centered around the Tree of Life, celebrating children and death. The holiday is traditionally observed by family gatherings, preparing special foods, singing in red robes on Kashyyyk, and exchanging gifts. Also, Bea Arthur runs a cantina on Mos Eisley for some unexplained reason.

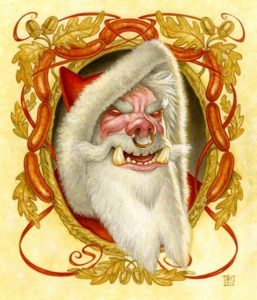

Hogswatchnight

Terry Pratchett’s 20th Discworld novel, Hogfather, is essentially a satire of modern Christmas customs. Hogswatchnight is described by the narrator as “bearing a remarkable resemblance to your Christmas.” The Hogfather rides his sleigh pulled by magically flying boars around the Disc delivering toys by climbing down chimneys. Children leave pork pies and brandy for the Hogfather, essentially a wild boar dressed in Father Christmas robes, which raises some disturbing questions about why he eats pork pies.

In the beginning, “Most people forgot that the very oldest stories are, sooner or later, about blood. Later on they took the blood out to make the stories more acceptable to children, or at least to the people who had to read them to children rather than the children themselves, and then wondered where the stories went.” Over the course of the book, there are zany hijinks and wacky shenanigans involving Tooth Fairies, elegant parties, the Auditors of the Universe, a governess, the Death of Rats, and various other Terry Pratchett wonders. Ultimately, Death (a seven foot tall skeleton with glowing blue eyes and a scythe) has to save the day. In doing so, he explains to his granddaughter (genetics are complicated) why celebrations of the sun’s return and surviving through winter are so important.