Last night I heard interviews with lawyers who recently visited the immigrant detention centers along the U.S./Mexico border. The conditions they reported were deplorable—inhumane, even. But what i want to focus on here is their observations that the border agents trying to do their jobs are massively stressed. So why do they stay there, doing what they’re doing?

This seems an appropriate time to remind writers that human motivation—and thus characters’ motivations—are complex things. What sort of SOB would do such things?

You can find stories all over the internet of people increasingly being treated inhumanely while trying to enter the U.S.—preschoolers being handcuffed, weeping mothers and young children separated for hours at a time, people held for twenty hours without food… Sometimes such stories suggest that it’s because of the things Pres. Trump says and does. His supporters are likely to reply, “No way in hell would he order such things! These are the acts of a few sick individuals.”

As writers, we don’t need to prove or disprove either of these causes. As writers, we know that almost anyone is capable of almost any act if the motivation is sufficient. What we may not have considered is just how easily ordinary people can be led to do extraordinary things.

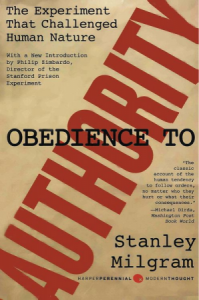

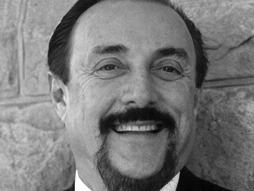

In 1963 Stanley Milgram first published his research on obedience to authority figures. The beginning of his research (1961) was with the trial of Nazi war criminal Adolf Eichmann in Jerusalem. He started with the question, “Could it be that Eichmann and his accomplices in the Holocaust were just following orders?”

The short answer is “Yes.” A very high proportion of people would fully obey the instructions, even if reluctantly, even if the acts ran counter to their own consciences.

![[Source]](http://vivianlawry.com/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/162203966-300x215.jpg)

The basic paradigm was that the subject thought he was the teacher, assisting the experimenter by delivering electric shocks to a learner whenever the learner gave a wrong answer. With each wrong answer, the apparent shock level was increased, finally to a point where the shocks—if real—would have been fatal. In the initial experiment, 65% of subjects gave the maximum shock level at least three times.

The important thing to remember is that the experimenter had no real authority over the subject delivering the shocks. The experimenter wasn’t a parent, a supervisor, a friend, a lover. The subject was not physically restrained from leaving. You can read all about it, in detail, in his 1974 book.

Variations on the original experiment revealed that a less official looking setting decreased obedience slightly. When the teacher was physically closer to the learner, the level of compliance decreased—but even when the teacher had to physically hold the supposed learner’s hand on what was supposed to be a shock plate, 30% completed the experiment. When the experimenter was physically farther away, compliance decreased. For example, when the experimenter gave instructions over the phone, compliance dropped to 21%. There was no significant difference in results when all women were used.

To write convincingly about obedience, it’s important to note that the people were greatly stressed by what they were doing. They objected verbally, questioned the experimenter, and reported high levels of distress when debriefed.

So, can we conclude that someone is telling people to get rough with those trying to enter the United States? NO!

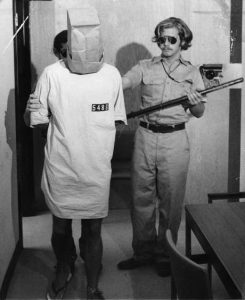

Enter Philip Zimbardo. In 1971 he conducted The Stanford Prison Experiment. It was specifically intended to investigate issues of the relationships between prisoners and guards. Did the behaviors of prisoners and guards reflect inherent personality differences between the two groups?

Volunteers for a two-week prison experiment were screened and those with criminal backgrounds, psychological impairment, or medical problems were excluded. The research team chose 24 men they deemed most psychologically stable and healthy. Participants were paid $15 per day (the equivalent of $92.91 in 2018).

The subjects were randomly divided into prisoners and guards.

The guards were instructed not to physically harm the prisoners or withhold food or drink, but Zimbardo emphasized that “…in this situation we’ll have all the power and they will have none.” Guards were told to call prisoners by their assigned numbers rather than their names. But otherwise, guards improvised their roles. Prisoners were given no instructions.

On the second day the three prisoners in one cell rioted, blocked the door with their beds, tore off their caps, and refused to come out or obey the guards. Guards from other shifts agreed to work overtime to quell the riot and eventually they attacked the prisoners with fire extinguishers (while not being supervised by research staff).

The experiment was terminated after only 6 days. By then, about a third of the guards had exhibited “genuine sadistic tendencies”; prisoners were emotionally traumatized and five of them had to be removed from the experiment early. You can read about this experiment in any social psychology textbook. Online you can also view video clips.

Arguably, the most important outcome of the study is that the behavior of two equivalent groups diverged dramatically after one was labeled “guards” and the other was labeled “prisoners.”

To answer the initial question of what sadistic SOB would do such a thing: the perfectly ordinary, likable, friend, colleague, or neighbor.

As a writer, keep that in mind as you create characters behaving badly.

I’ve always found the Milgram experiment fascinating, especially because it was inspired by his Jewish heritage and the fate of his family members during the Holocaust. What a perfect question for him to ask – How can someone participate in an atrocity? Equally fascinating – How can some see an atrocity and do nothing about it? I can think of many literary characters in that second camp that, I think, cause me to look more at myself. It’s easy to think I wouldn’t help run a concentration camp, for instance. But would I do something to stop it from running?

Thoughtful and such a real response. Thank you! I’ve always found these experiments as powerful as they are disturbing.

also confirming that pretty much anyone at any time can cause harm see

Albert Bandura on Moral Disengagement at https://albertbandura.com/albert-bandura-moral-disengagement.html

“In the development of a moral self, individuals adopt standards of right and wrong that serve as guides and deterrents for conduct. They do things that give them satisfaction and a sense of self-wroth. They refrain from behaving in ways that violate their moral standards, because such conduct will bring self-condemnation. These positive and negative self-sanctions keep behavior in line with moral standards. However, in a pervasive moral paradox, people in all walks of life behave harmfully and still maintain a positive self-regard and live in peace with themselves. They do so by disengaging moral self-sanctions from their harmful practices. These psychosocial mechanisms of moral disengagement operate at both the individual and social system levels.”