I’ve written before of the benefits for writers as well as for readers in expanding your cultural horizons. With Halloween upon us, what better time to discuss cultural variations in death, dying, and what to do after? A particularly tragic element of the current pandemic inspired this particular blog post.

Although not comprehensive, COVID-19 statistics indicate that the death rate for American Indians/Alaskan Natives is 3.5 times the rate for non-Hispanic white people. The upshot is that I was moved to explore beliefs, traditions and customs related to death among native peoples.

I used the plural on purpose.

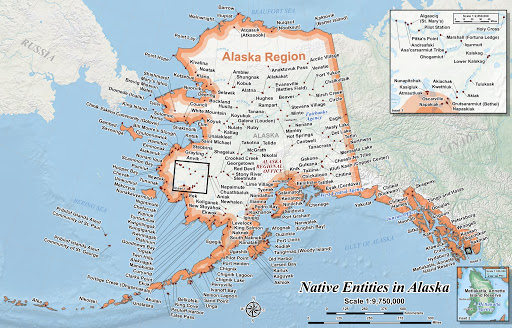

There are 574 federally recognized Indian Nations in the United States. I was surprised to learn that the labels nation, tribe, band, pueblo, community, and native village all are applied to ethnically, culturally, and linguistically diverse groups of people. Approximately 229 of these nations are located in Alaska; the other federally recognized tribes are located in 35 of the lower forty-eight states.

No slight to Alaskan Natives is intended, but this is a blog—albeit a long one—not a book, so I can only skim the customs and ceremonies of Native Americans. Further information about death and burial customs among tribes in Alaska is available on the Alaskan government website, several articles on JSTOR and other scholarly archives, and among training materials for healthcare workers who might be present at the end of life.

BTW, beyond the 574 federally recognized tribes, there are state government-recognized tribes located throughout the United States.

According to Michele Meleen, many tribes share beliefs about death and burial in general.

- Each person has a soul or spirit that leaves the body after death.

- Traditional burials take much longer than a modern funeral, up to several days, because the spirit of the person lingers before moving on.

- Family and tribe members must help the spirit along its way through rituals and ceremonies.

- Autopsies are avoided if at all possible because cutting open the body might prevent the spirit properly beginning its journey.

According to Klaudia Krystyna, there are further similarities in what varying tribes believed.

- Most Native Americans worshiped an all-powerful Creator or spirit.

- They believe in deep bonds between earth and all living things.

- They also unite in a belief about an afterlife, with death beginning the journey that is a continuation of life on earth.

- Many believe in reincarnation, coming back as another person or animal.

- The type of person or animal depends on one’s deeds when alive, a bit like the Hindu cycle of reincarnation.

That said, in reality, the death practices in each tribe are unique. In today’s society, there is a tendency to view the immense variety of Native American cultures as all the same. Kara Stewart, a Sappony author and teacher, discussed the issues involved in authentic writing in an interview on The Winged Pen. As she said, “With over 567 very different sovereign federally-recognized nations and hundreds more sovereign state-recognized nations, nuance is everything.”

Given the number of tribes of Native Americans, what follows is just a sample of traditional Native American practices prior to the arrival of Christianity.

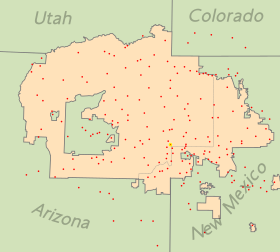

Navajo (Diné)

The Navajo tribe, also called the Diné, are the largest American Indian Nation. Currently, the Navajo nation covers approximately 17,544,500 acres in parts of Utah, Arizona and New Mexico. The tribe is divided into more than 50 families whose lineage can be traced matrilineally.

The religion and beliefs of the Navajo, like the Sioux (below), are based on animism.

One of the common Navajo beliefs about death was that the deceased goes to the underworld when he or she dies. Precautions must be taken to ensure that they don’t return to the world of the living. Navajos were very reluctant to look at a dead body. Contact with the body was limited to as few individuals as possible because contact with a corpse can bring sickness, misfortune, or even death.

If a person died at home, then the dwelling and everything in it were destroyed. Therefore, when death was near, the person was taken outdoors, or to a separate hut, to die. Family members and the medicine man stayed until close to the end. Shortly before death, everyone except for one or two individuals left. Those who remained would be the closest relatives of the dying person, those most willing to expose themselves to evil spirits.

Four men did all of the tasks involved in the burial of the body.

After death, two men prepared the body for burial. They wore only moccasins. Before starting, they smeared ash all over their bodies to protect them from evil spirits. Before burial, the body was thoroughly washed and dressed. It was believed that if the burial was not handled in the proper fashion, the person’s spirit would return to his or her former home.

While the body was being prepared, two other men dug the grave as far a possible from the living area. The funeral was held as soon as possible, usually the next day. Those four men were the only ones present at the burial.

The dead person’s belongings were loaded onto a horse and brought to the grave site, led by one of the four mourners. Two others carried the body on their shoulders to the grave site. The fourth man warned those he met on the way that they should stay away from the area. Once the body was buried, great care was taken to ensure that no footprints were left behind. The tools used to dig the grave were destroyed.

Sometimes the property of the deceased was disposed of by burning. In any event, none of it was left at home.

According to some customs, after the body was cleaned, the face was coated with chei (paint made of soft red rock, crushed and mixed with sheep oil) for protection during the journey. The body was dressed in his or her best clothes, hair tied with eagle feathers symbolizing the return to the homeland.

Another variation in customs: three family members wrapped the prepared body in a blanket and laid it across the back of a clean horse. One man leads the horse to a suitable burial place (such as a secure cave). At the burial place, the dead person was interred with saddles and all personal belongings. After the body was buried, the horse was slaughtered and buried as well, to aid the deceased on the journey to the afterlife.

There was also the custom of burying the dead as far north as possible, to help the soul move on to the next journey more quickly.

According to traditional Navajo beliefs, birth, life, and death were all part of a natural, ongoing cycle. Crying and outward demonstrations of grief were not usual when someone died, because showing too much emotion can interrupt the spirit’s journey to the next world. The spirit could attach itself to a place, an object, or a person if the proper process was interrupted.

Sioux/Dakota

The Sioux Nation is the second largest Native American Nation, comprised three major divisions based on language/dialect: the Dakota, Lakota and Nakota (Yankton-Yanktonai).

The Sioux tribe (like the Navajo) believed in Animism, that the universe and all-natural objects—animals, plants, trees, rivers, mountains, rocks, etc.—have souls or spirits.

Sioux did not fear the souls of the dead. In general, the Sioux believed that death was the beginning of another spiritual journey. They held that the soul of the deceased lingered four days before leaving for the next resting place.

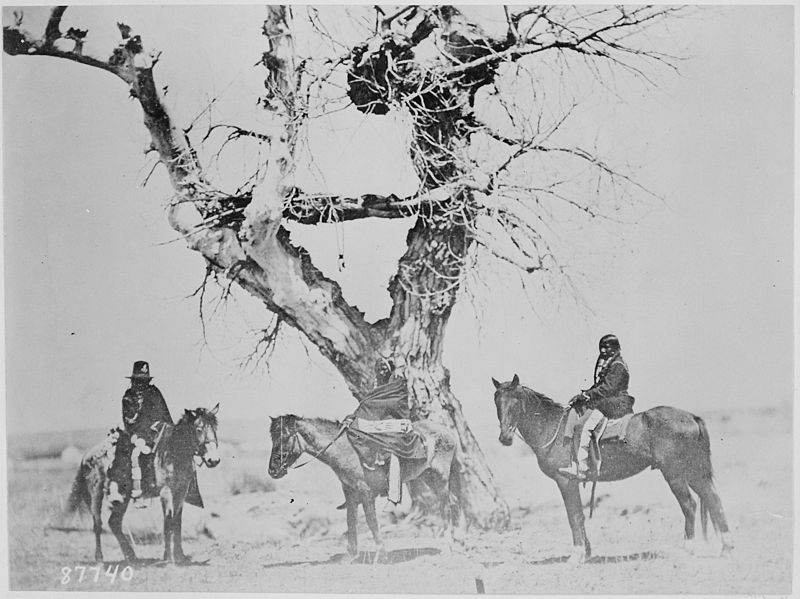

Traditionally, Sioux people put the body of the dead person in a tree, or on a scaffold in a tree about eight feet above the ground.

The remains were left there for a year, and treated as if still alive. The body was dressed in the best clothes, and surrounded by personal property. Fresh food was provided for the soul.

Today, many Sioux practice both traditional and modern Christian death rituals. (See below.)

Cherokee

For the Cherokee, the funeral begins with prayers led by the shaman. During the service the shaman prays on behalf of the deceased and offers spiritual lessons to the living. The funeral ends in prayer and the body is carried to its final resting place on the shoulders of the funeral procession.

Chippewa/Ojibwe

The Chippewa are known in Canada as Ojibwe, Ojibway, or Ojibwa. They lived mainly in Michigan, Wisconsin, Minnesota, North Dakota, and Ontario, occupying large areas of land. Their way of life belongs to the northeast woodland cultural groups. Their population in the United States ranked fifth in the indigenous tribes, behind the Navajo, Cherokee, Choctaw and Lakota-Dakota-Nekota peoples. One well-known scholar who wrote extensively of the Chippewa way of life was Sister M. Inez Hilger, O.S.B.

In the Chippewa culture, they believed that the spirit would leave the body after it was buried, rather than at death, so they preferred to bury it immediately. Simultaneously, they also traditionally believed that it would take four days to achieve a happy death for the spirit of the dead. These two beliefs drove their rituals, as family members considered it their duty to help the spirit move forward.

If someone died in the morning, the body would be buried the same day to help the spirit reach the happiness sooner. If the body had to be kept overnight, people would go to the victim’s house, not only to spend time with the grieving relatives but also to be with the person who was lying there.

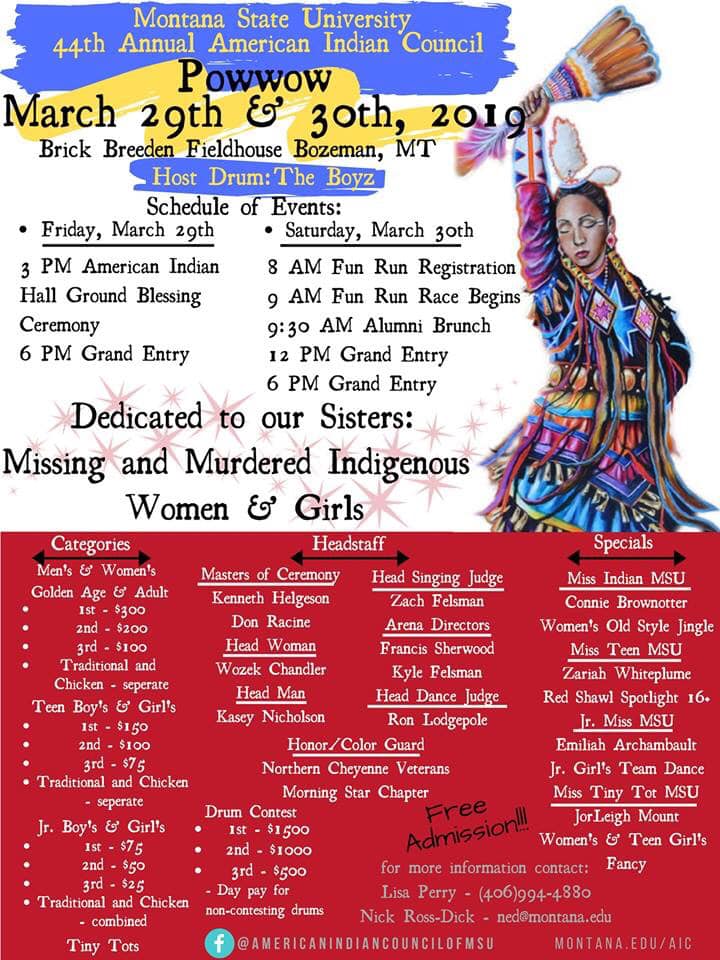

A pow-wow was held at the deceased’s home the night after the burial. Before dark, a fire was lit at the head of the grave, and this fire was lit every night for four nights to help guide the spirit.

At the end of the fourth day after burial, a medicine man presided over a feast and was responsible for giving away all the deceased’s belongings. Each person who received an item must give a new piece of clothing in return. All these new clothes were wrapped in a bundle and given, along with a dish, to the closest living relative. This person then handed out the new clothing to those he/she felt worthy.

The deceased’s loved one keeps the dish and carries it for one year to every meal he or she attends. It is filled with food to honor the deceased.

Kiowa

According to Toby Blackstar, a Native American funeral director, the Kiowa believe in-ground burial is the only acceptable way to release a body after death. They believe the Creator birthed the body from the earth, so it must return to the earth through decomposition.

For the Ponca Tribe within the Kiowa, there is a fear of the deceased which drives their death rituals. They are afraid the dead will resent them and the ghost will haunt anyone with his/her possessions. So, the tribe burns all of the deceased’s possessions, even if they are valuable. Any remaining family members who shared a house with the deceased person then moved into a new house.

Comanche

The burial customs for early Comanches were pretty simple. The body was not kept long prior to a proper burial. The deceased would be wrapped in a buffalo robe (or, later, blankets). The body was placed on a horse and taken to a burial place such as a cave or crevice in a rocky canyon. Burial sites would be in areas such as the Wichita Mountains and the slick hills or limestone hills of southwest Oklahoma. Personal items of the Comanche were placed in with the body and rocks were carefully placed on top to cover the deceased. It wasn’t until the Comanches came into contact with the early missionaries that they began burying their fellow Comanches in cemeteries.

Choctaw

From the middle to late nineteenth century, the Choctaw favored burying their dead directly in the ground. The deceased was buried in a seated position. Seven men placed seven red poles about the grave, with thirteen hoops of grapevines and a small white flag.

Iroquois

As a general practice, these tribes buried their dead in graves and traditionally took a more vengeful approach to death. They practiced revenge through torture of the person responsible for a loved one’s death, but these practices evolved into required payments of money rather than life. Taking a man’s life cost ten strings of wampum and taking a woman’s life cost twenty because she was valued for her ability to have children.

If a loved one was killed by a person from another tribe, the matriarch of that person’s family could ask tribal warriors to take a prisoner from the tribe of the murderer. These mourning wars often involved a planned raid on another tribal village for that sole purpose.

Once captured, the matriarch would choose whether the prisoner was adopted into her family or tortured based on her level of grief. If torture was chosen, all village members had to take part as a signal of ending the person’s old life. The Iroquois valued strength in numbers, so the tortured prisoner would often get adopted into the tribe as a replacement for the person they lost.

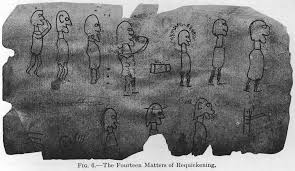

At some point in history, these mourning war practices were replaced by the Condolence Ceremony, particularly for clan and tribal chiefs. During this ceremony, members of several tribes would come together to mourn the loss as a nation rather than just the deceased’s family mourning a family member on their own.

These sacred ceremonies have not been well documented because they are deeply personal to Iroquois tradition. What is known is that leaders of another tribe were charged with conducting the ceremonies which included recitations of actions individuals could take to grieve the loss as well as comforting words. A string of wampum was presented by all the nations as one for each specific recitation, which could vary by tribe and circumstance.

From Then to Now

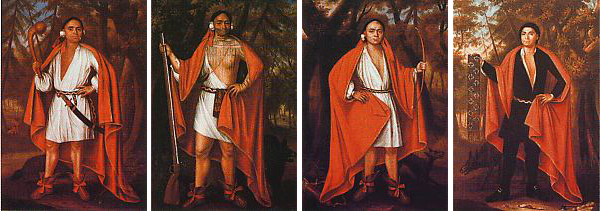

When Europe began to colonize America, European settlers brought great changes in Native American culture.

Eventually hundreds of tribes and ancient traditions disappeared.

The “mission” of Christian missionaries was to change the tribe. In 1882, the federal government of the United States attempted to ban the religious ceremonies of Indians and said they were “against public decency and morality”. Since the 19th century, some Native Americans have converted to some form of Christianity—becoming Catholics, Presbyterians, Jehovah’s Witnesses, or whatever.

Although modern Native American death ceremonies have changed radically, often these practices still contain elements of traditional beliefs. A current ceremony often mixes traditional practices with elements of Christianity or other religions.

Tribes who converted to Catholicism celebrate All Souls’ Day on 1st November, commemorating the dead. Related to the Mexican festival of Dia de los Muertos, on this day Native Americans would leave food offerings and decorate their homes with ears of corn. The Chippewa way of death is similar to Hindu.

One modern practice by the Oneida Nation is the Community Death Feast. These annual feasts are held once each spring and once each fall to honor those who have died. Each person in the community brings a traditional food like corn mush, wild berries, wild rice, or venison to share with the whole group. One plate is filled with some of each shared dish and placed in a private area just before sunrise as a token for the dead.

One expanded example of the old being melded with the new: modern Sioux burials last four days before the dead are buried. The casket is rolled up a short ramp onto a scaffold eight inches above the floor, in the middle of the room. Flowers are arranged around the casket.

Family stand near the coffin. Mourners greet them, and gifts for the deceased (e.g., knives and shawls) are placed in casket before burial. The moderator reads the obituary, talks about the life experience of the deceased, and invites the people participating in the funeral to talk about their experience with the deceased. Then prayers start praying, and all participants pray, and sing an honor song in the traditional Sioux language. The participants walk counterclockwise in the hall.

At night, a thin layer of purple lace is laid on top of the opening of the casket to prevent evil spirits from taking the spirit of the dead. This is a common practice among the Santee Sioux because bad spirits are most active at night. The Santee Dakota, known as the Eastern Dakota, was established in 1863 and reside in the extreme east of the Dakotas, Minnesota, and northern Iowa. The last watch is held at midnight, and everyone stays overnight. At least one family member has to stay with the deceased overnight until the burial.

The next three days are the same as the first day, with the obituary, praying and songs of honor. After each ceremony, friends and family take turns paying their respects to the deceased, giving him/her “spiritual food” called wakan or pemmican to help the spirit move along the journey.

When the casket is lowered into the grave, those who carried the casket each shovel earth into the grave. People who wish to sprinkle a handful of dirt onto the casket. The men carrying the coffin had the job of filling the grave. More prayers and songs follow. Finally, everyone leaves to enjoy a last meal together.

BOTTOM LINE:

Sacred Native American traditions and ceremonies are most often preserved in oral history, and taught to the next generation by word of mouth. These ceremonies and beliefs are not always documented outside of oral tradition. Each medicine person specializes in different ceremonies. When someone dies they take that knowledge with them. Over the last several decades, the Diné/Navajo medicine people has gone from a thousand to just 300. The coronavirus threatens the few who remain. Potentially, COVID can decimate both populations and culture among Native American peoples.

Additional Information

- Writing About Native Americans

- Native American Death Rituals

- Indian 101 for Writers

- Indian 101 for Writers, Part 1: Know Thyself

- Indian 101 for Writers, Part 2: Know Whereof You Speak (a.k.a. Don’t Make It Up or Rely On What You *Think* You Know)

- Indian 101 for Writers, Part 3: Keep It Real, People

- Indian 101 for Writers, Part 4: Aargh!

- Indian 101 for Writers, Part 5: Walking In Two Worlds

- American Indians in Children’s Literature

- “You have stolen everything from us”: Progressive Perspectives in The Revenant

- Terms and Issues in Native American Art