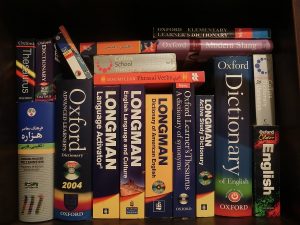

You may know that I love dictionaries! Indeed, I have four shelves of dictionaries that look much like the above—only less photogenic! And I’ll tell you right up front that my goal for today is to turn your liking for dictionaries into loving. After all, words are the building blocks of stories, the most basic tool of the craft. And dictionaries contain a wealth of information.

Why one dictionary isn’t enough:

1. Language is constantly evolving. New words are added every year. So, depending on the time when you set your story, you may need an “age appropriate” dictionary. The current vocabulary is so important that books that are not actual dictionaries nevertheless have sections on language, books such as Everyday Life In The Middle Ages, Everyday Life in Colonial America, etc. The timeliness of language is particularly true for slang. Heaven forbid you should drop “far out” (meaning extraordinary or bizarre in the 1960s) into a story set in the 1950s. And there are dictionaries for that!

2. Language varies by occupation or profession. I have dictionaries that focus on war slang by war, a dictionary of jargon by profession, a dictionary of mob speak.

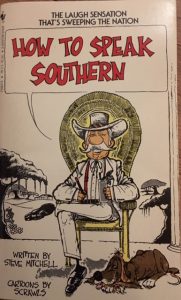

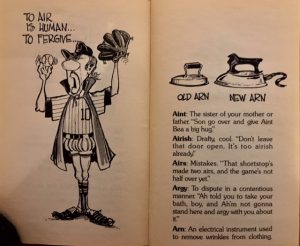

3. Language is regional as well as time specific. I have dictionaries of American English (so labeled), Australian English, and South African English—and there are probably more out there reflecting English as spoken around the world. But some, such as Yankee Speak, are much closer to home. How To Speak Southern, published in 1976, may be dated (or not) depending on when your story happens. But in any case, it’s short and worth a read just for the laughs.

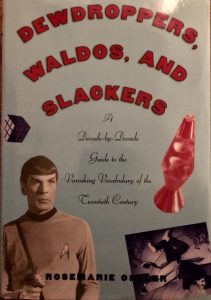

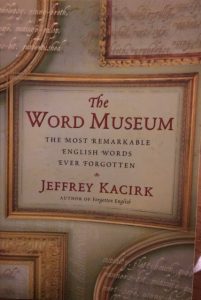

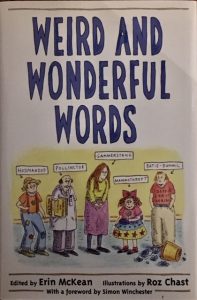

4. Using archaic words can spice up your writing as long as the context makes the meaning clear. For example, biblioklept (meaning book thief), fleshquake (a tremor of the body), or crop-lifting (to steal a crop of standing grain).

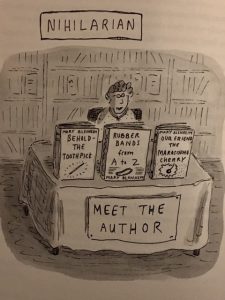

5. Actually—and perhaps not surprisingly—I especially like dictionaries of weird words. Where else would one come across words like “nihilarian” (meaning a person who deals with things of no importance)?

Of course, one person’s “no importance” is another person’s passion! So a character using that label/word says a lot about the speaker. Indeed, a character who’s makes a habit of using esoteric words is rich with possibilities!

6. And then there are common, easily understood words that are seldom used. Some of these are very personal. For example, my high school English teacher had an explicitly stated aversion to the word “bother” and urged saying “it isn’t” rather than “it’s not” because the latter sounded too much like snot. Consider dropping uncomfortable words into your narrative and/or dialogue to create a bit of unease or tension in the reader, and/or to characterize your character. Consider your—or your character’s—uncomfortable words.

7. Why not just look words up online? Now this is getting personal to me. If you need to check the spelling and/or definition of a particular word, the internet is quick and dirty—i.e. efficient. The problem (in my opinion) is that you get what you ask for. With a physical dictionary, you can easily tumble into reading nearby entries. So you look fulminate (criticize harshly) and wander into fulsome (sickening or excessive behavior)—and there’s a whole new adjective you can use!

Bottom line: We all know writers read. Try reading a dictionary or two!