Collective nouns fascinate me, as I’ve mentioned before. I’ve heard a group of starlings called a “murmuration” most often, but I’ve also seen

- A chattering of starlings

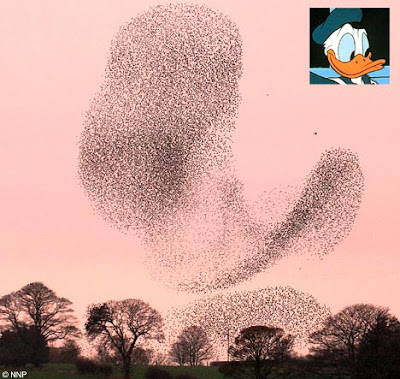

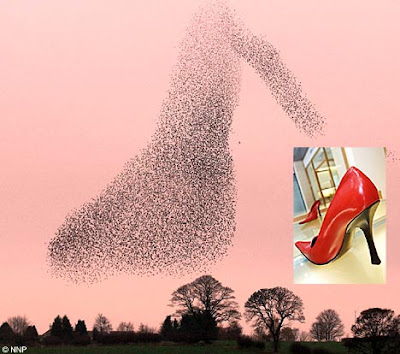

- A cloud of starlings

- A clutter of starlings

- A congregation of starlings

- A flock of starlings

- A scintillation of starlings

In mid-January, a starling showed up at our bird feeder. A week or so later, we saw two. A few days ago, we had a whole clutter of them!

Starlings are boisterous, loud, and they travel in large groups (often with blackbirds and grackles).

Attractive Starlings

Their appearance changes with age and seasons. Young ones are more brown than black.

In fresh winter plumage they are brown, covered in brilliant white spots. In summer they are purplish-green iridescent—but not as blue-black iridescent as grackles.

Their legs are officially pink, though I’ve always thought they look more yellow. The bill is black in winter and yellow in summer.

Bigger than chickadees, smaller than blue jays, starlings seem to me to be about the size of cardinals.

Starlings have diverse and complex vocalizations and have been known to embed sounds from their surroundings into their own calls, including car alarms and human speech patterns. The birds can recognize particular individuals by their calls and are the subject of research into the evolution of human language.

Starlings are active, social birds. Pet starlings notoriously bond closely with their caretakers and seek them out for companionship. Although wild birds, they are easy to tame and keep as pets. Their normal lifespan is about 15 years, possibly longer in captivity.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart kept a pet starling for several years. He may have written his Piano Concerto No. 17 in G, (K. 453) as an adaptation of the bird’s song. When it died, Mozart held an elaborate funeral for it, calling on all the mourners to sing the bird a requiem in procession.

“Come Here” Starlings

As the story goes, Eugene Schieffelin—an eccentric pharmacist in the Bronx—was an Anglophile and a Shakespeare aficionado. As deputy of a group whose goals included introducing European species that would be “interesting and useful” and benefit homesick immigrants. Schieffelin, it is believed, latched onto the goal of bringing every bird mentioned in the works of Shakespeare to Central Park, and he zeroed in on the Bard’s single reference to a starling in Henry IV.

HOTSPUR: He said he would not ransom Mortimer,

Henry IV, Part 1 (Act I, Scene 3, Line 228)

Forbade my tongue to speak of Mortimer.

But I will find him when he lies asleep,

And in his ear I’ll hollo “Mortimer.”

Nay, I’ll have a starling shall be taught to speak

Nothing but “Mortimer,” and give it him

To keep his anger still in motion.

However, according to Eugene Schieffelin’s obituary in 1906, he imported starlings for an entirely different reason — to wage war on a particular type of caterpillar that was invading his garden. In fact, researchers at Alleghany College published an article in 2021 arguing that the story of Schieffelin’s obsession with Shakespeare grew out of social and political anti-immigrant sentiments common at the end of the 19th and early 20th centuries.

In any case, starlings are an introduced species to America and have adapted well to urban life, which offers abundant nesting and food sites. It took them just 80 years to populate the continent. They are a ubiquitous, nonnative, invasive species. There are so many that no one can count them—estimates run to about 200 million. Genetic research shows that all of these millions of birds descended from the original 80 or so birds Eugene Schieffelin released in Central Park. They’ve behaved atrociously in their New World.

Despised Starlings

Starlings can damage grass turf as they search for food. While looking for worms, the extremely strong beaks of these birds often damage the root systems of the grasses they pull up. Large flocks can destroy crops in your garden and disturb your newly seeded lawn when the birds feed on seeds and berries.

The US Department of Agriculture officially classifies European starlings as an invasive species. Many biologists despise starlings for their reputed ability to outcompete native birds for food and a limited number of nest sites.

They nest in cavities, and each spring they seek crevices in buildings, homes, and birdhouses, as well as holes that have been carved into trees and poles by woodpeckers. They compete for these sites with other cavity nesters, including chickadees, bluebirds and swallows. Because starlings do not have to migrate south for the winter, they are able to claim the best nesting sites before breeding season begins.

This is my major concern: that a clutter of starlings will drive out native Virginia birds currently in our backyard (goldfinch, cardinal, blue jay, tufted titmouse, house finch, blue birds, woodpeckers, chickadee, flicker, wren, brown thrush, even the occasional sharp-shinned hawk and (a few) mockingbirds.

One hopeful possibility: “The evidence that this competition has led to significant population declines is pretty slim, at best,” says Walter Koenig, ornithologist and researcher.

Also, one significant point to remember: starlings thrive in areas that are disturbed by human presence, including dense urban environments, places where more sensitive species cannot survive in the long term. Maybe native birds are simply finding more hospitable locations.

Disastrous Starlings

However, starlings can cause actual public disasters. In 1960, Eastern Airlines Flight 375 took off from Boston’s Logan Airport for Philadelphia and other points south. Seconds after takeoff, it collided with a flock of 20,000 starlings. Two of the four engines lost power, the plane plunged into the sea, and 62 people died. This remains the worst airline crash—in terms of human fatality—that was ever caused by a collision with birds. See the 2017 article Even If We Don’t Love Starlings, We Should Learn to Live With Them by Lyanda Lynn Haupt.

From the same article: “After that crash, officials tested seasoned pilots on flight simulators to see if any could have saved the plane in such a scenario. All failed. In subsequent tests, live starlings were thrown into running engines. It was found that just three or four birds could cause a dangerous power drop.”

Although starlings’ ecological sins might be overstated, their devastating effects on agriculture are beyond doubt.

Starlings damage apples, blueberries, cherries, figs, grapes, peaches, and strawberries. Besides causing direct losses from eating fruits, starlings peck and slash at fruits, reducing product quality and increasing the fruits’ susceptibility to diseases and crop pests. They also lurk around farmyards and lots where they binge on feed in the troughs of cattle and swine.

The US Department of Agriculture counts the devastation as high as $800 million annually. Some researchers estimate that starling cause approximately $1.6 billion of damage to crops and livestock every year.

Dealing with Starlings

The good news is that for the last thirty years or so starling populations have been stable. Every species has a carrying capacity, the number of individuals that can thrive in a given place without exhausting resources, and perhaps starlings are there.

Ecologically, starlings’ presence lies somewhere between highly unfortunate and utterly disastrous.

Starlings are not protected in Virginia or by the federal government, which means that we can remove the starlings and their nests at any time of the year. We might also fill the bird feeders with food they don’t like, block potential nesting sites, and prune trees to deny cover for flocks. If these starlings turn out to be particularly stubborn, we might even play recordings of hawks and predator calls or simply bang pots outside to drive them off.

Bottom Line: Whatever a bunch of starlings are called, they are definitely a nuisance—maybe even a disaster!