Workshop of the Ripley Foundry and Machine Factory

from Ohio Historical Society

A couple of weeks ago, I mentioned that (among other things) August is Black Business Month. And then I heard about John P. Parker. He caught my attention because 1) my father’s name was John E. Parker; and 2) both moved to Ohio from points farther south, and died there.

Although there’s no other connection, that was enough to make me want to find out about this historical Parker—and an amazing man he was!

An Eventful Early Life

John P. Parker was the son of a slave mother and white father—name unknown, but reputed to be a Virginia aristocrat. At the age of eight, John was chained to another slave and forced to walk from Norfolk to the slave market in Richmond, VA. There he was resold and added to a chained gang of 400 slaves being herded to Mobile, AL. In Alabama, he was bought by a local physician.

Encyclopedia of Virginia

Parker worked first as a house slave and companion to the doctor’s two sons. According to John’s memoir, he became good friends with the two boys and enjoyed being their playmate. Although educating a slave was against the law, the doctor’s sons secretly taught Parker to read and write.

When the sons went to Yale, John was supposed to go with them as their personal servant. However, in Philadelphia, the difference in public sentiment regarding slavery became obvious. Afraid that abolitionists would try to free John, the doctor’s sons sent him back to Alabama. His dreams of university were dashed.

John Parker returned to Mobile, where the doctor apprenticed him to a plasterer. The plasterer was a brutal drunk and after defending himself, Parker feared for his life and fled by riverboat. After months of pursuit and escape—well worth reading about!—he ended up on the docks in New Orleans. In a bizarre coincidence, Parker happened to cross paths with the Alabama physician and returned to Mobile. According to his memoir, Parker was quite happy to accompany the doctor home.

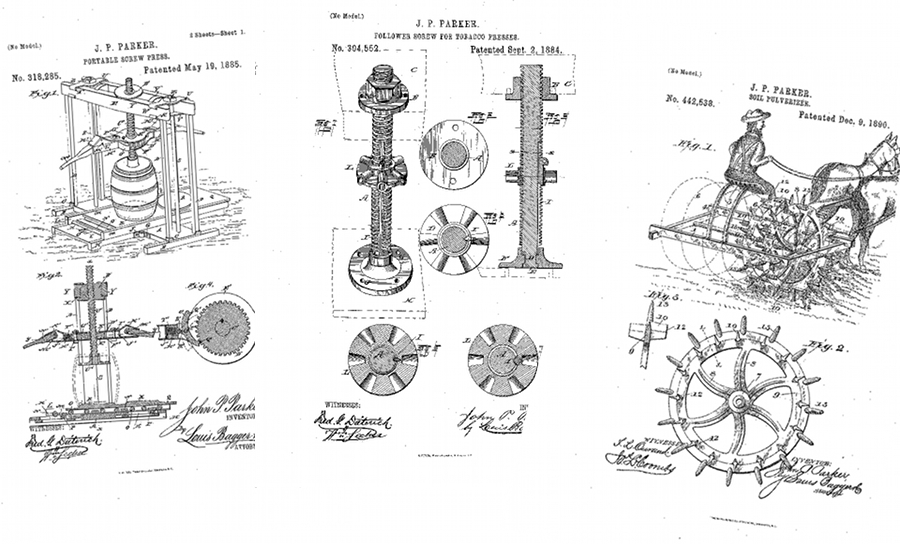

Returned to the doctor’s household, John was apprenticed again to a foundry. He thrived and learned there until he got into a fight with his boss. The doctor sent John to work in another friend’s foundry. Again, John’s temper ended in a fight with the superintendent. The argument was compounded by the superintendent’s theft of Parker’s design for an improved tobacco press. Fortunately, the superintendent was unfamiliar with patent law, and Parker was able to file the patent when he was a free man.

After this, the doctor claimed he didn’t know what to do with John and would have to to sell him as a field hand.

Finding Freedom

Desperate to avoid the brutality of a field hand’s life, John asked one of the doctor’s patients, a widow, to purchase him. He persisted in his petitions until she agreed to do so, for $1,800.

Elizabeth Ryder, the widow, allowed John to hire himself out to earn money. She agreed that his wages could be used to purchase his own freedom. John Parker repaid that $1,800 plus interest at the rate of $10 per week. He earned the money doing piecework in Mobile iron foundries, as well as occasional odd jobs and running a “regular three-ball pawnshop.”

Parker was so motivated to repay Mrs. Ryder that he paid her far more than $10 every week.

John Parker gained his freedom in 1845, after eighteen months with the widow. This is a pretty amazing achievement: that $1,800 (never mind the interest) is the equivalent of $64,659 today. He was only 18 in 1845! Clearly, he was both hard working and talented. And thanks to Mrs. Ryder, who “gave me a free hand to go where I wanted to and do as I pleased.”

Businessman

Beginning as an iron molder, Parker developed and patented a number of mechanical and industrial inventions, including the John P. Parker tobacco press and harrow (pulverizer), patented in 1884 and 1885. He had actually invented the pulverizer while still in Mobile in the 1840s. Parker was one of the few blacks to patent an invention before 1900.

from Small Farmers Journal

In 1865, Parker and a partner bought a foundry, which they named the Ripley Foundry and Machine Company. “Parker managed the company, which manufactured engines, Dorsey’s patent reaper and mower, and sugar mill. In 1876 he brought in a partner to manufacture threshers, and the company became Belchamber and Parker. Although they dissolved the partnership two years later, Parker continued to grow his business, adding a blacksmith shop and machine shop. In 1890, after a destructive fire at his first facility, Parker built the Phoenix Foundry. It was the largest between Cincinnati and Portsmouth, Ohio.” (Wikipedia)

Family Man

I find John Parker’s personal life as impressive as his business achievements. After buying his freedom, Parker settled first in Jeffersonville, Indiana, then Cincinnati, Ohio. The port city of Cincinnati had a large free black community, with a variety of work available. In 1848, he married Miranda Boulden, free born in that city. They had a small general store at Beechwood Factory, Ohio, but a year later moved to Ripley. There they had seven children together, though some sources only include six.

- John P. Parker, Jr, b. 1849, attended Oberlin College but died before graduating, in 1871

- Hale Giddings Parker, b. 1851, graduated from Oberlin College‘s classical program and became the principal of a black school in St. Louis

- Later, he studied law and in 1894 moved to Chicago to become an attorney

- Cassius Clay Parker, b. 1853 (the first two sons were named after prominent abolitionists)

- He studied at Oberlin College and became a teacher in Indiana.

- Horatio W. Parker, b. 1856, became a principal of a school in Illinois

- He later taught in St. Louis.

- Hortense Parker, b. 1859 was among the first African-American graduates of Mount Holyoke College

- After marriage in 1913, she moved to St. Louis and continued to teach music.

- Her husband was a college graduate who served as principal of a school.

- Portia, b. 1865, became a music teacher

- Bianca, b. 1871, became a music teacher

In one generation from slavery, all seven of John Parker’s children were college educated. John and Miranda are noted in local records as owning the area’s largest collection of books, which they frequently loaned to neighbors in support of education.

Interestingly, in his will, John Parker forbade any of his children taking over his businesses. He wanted them to be upwardly mobile in the professions and Black middle class.

Abolitionist

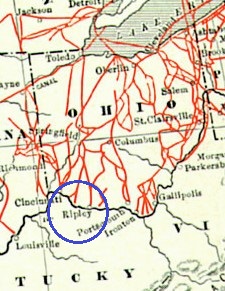

Ripley, OH was in an area of growing abolitionist activity when John Parker moved there, and who is to say whether he would have been as much involved in the movement if he had lived elsewhere? Perhaps not.

But while living in Cincinnati, Parker boarded with a barber whose family was still held in slavery. Parker’s first successful extraction was to rescue the barber’s family from and eventually rescued the barber’s family from slavery—his first successful extraction—and it was launched from and came to a successful close in Ripley.

Ripley, so close to the Ohio River that separated slavery from freedom, was a natural station for the Underground Railroad.

Parker joined the resistance movement there, and for 15 years aided slaves escaping across the river from Kentucky to get farther north to freedom; some chose to go to Canada. Parker guided at least 440 (some sources put the number as high as 1,000) fugitives along their way, despite a $1,000 bounty placed on his head by Kentucky slaveholders. The federal Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 increased the penalties for aiding escaping slaves.

Although he was known for keeping meticulous records of the people passing through Ripley, John Parker was equally meticulous in maintaining the secrecy of his Underground Railroad station. When he received word that someone had reached safety, Parker burned the records relating to that person. He insisted that his photo not be taken, and there is no confirmed photograph of him. When the Fugitive Slave Act was passed, Parker dropped his entire book of fugitives’ names, dates, and original homes into the cupola of his own iron foundry.

Parker risked his own freedom every time he went to Kentucky to help slaves to freedom. According to the Cincinnati Commercial Tribune, “He would go boldly over into the enemy’s camp and filch the fugitives to freedom.” During the Civil War, he recruited a few hundred slaves for the Union Army.

But Ripley, like many towns in non-slave states, wasn’t united in support of escaping slaves. Residents on opposite sides of the issue often ended in physical conflict. In Parker’s own words, “I never thought of going uptown without a pistol in my pocket a knife in my belt, and a blackjack hand. Day or night I dare not walk on the sidewalks for fear someone might leap out of a narrow alley at me.” Even so, he helped at least 440 fugitives to flee.

from the Ohio Historical Society and John Parker House

Parker’s Memoir

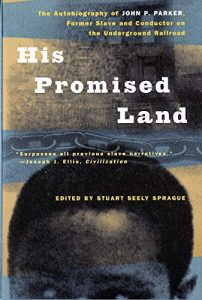

Parker’s story in his own word—HIS PROMISED LAND: The Autobiography of John P. Parker, Former Slave and Conductor on the Underground Railroad— wasn’t published until 1998. Parker gave interviews to the journalist Frank Moody Gregg of the Chattanooga News in the 1880s, when Gregg was researching the resistance movement. He never published this manuscript, but historian Stuart Seely Sprague found Gregg’s manuscript and notes in Duke University Archives. He edited the document for publication, keeping Parker’s language, and added a detailed biography in the preface.

The documents are still accessible in the Duke University archives online.

I’m calling it a memoir rather than an autobiography because this book is limited to Parker’s early life and his involvement with the Underground Railroad. It’s a fast, gripping read, but if you want to know about his business or personal life, you must look elsewhere.

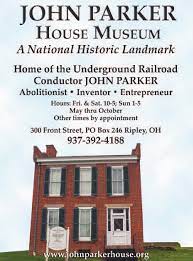

The John P. Parker House

Parker’s house at 300 N. Front Street in Ripley, Ohio, is a National Historic Landmark. It is a small museum, open to the public Friday-Sunday, May-October.