Today’s blog entry was written by Kathleen Corcoran, a local harpist, writer, editor, ESL teacher, luthier, favorite auntie, turtle lover, canine servant, and cinephile.

If you’re like me, reading a book is like watching a film inside your head. Casting is entirely up to your imagination, there’s no need for stunt doubles, and the special effects budget is unlimited. It even comes in Smell-O-Vision, which is not always fun.

To learn more about how a writer’s mental movie is translated into a box office hit, I spoke with Sean Williams, a film producer, director, actor, and writer. Williams recently graduated George Mason University, where he directed No Endings, winner of the 2022 Mason Film Festival award for Best Horror/Thriller Film.

Sight and Sound

Alfred Hitchcock said, “A lot of writers think they’re filling the page with words, but they’re filling the screen with images.”

Every writing teacher’s favorite bit of advice seems to be “Show, Don’t Tell.” That is even more true on film than in prose. A film writer must convey everything to the audience entirely through visual or audio input. The sense of dread, nauseating smells, motion sickness, feeling hungry, nostalgia, and every other part of the story must be either seen or heard.

Screenwriters have lots of techniques they can use to provide background information. Voice-over narration, overheard radio or television broadcasts, shots of newspaper headlines, letters, text messages all provide exposition.

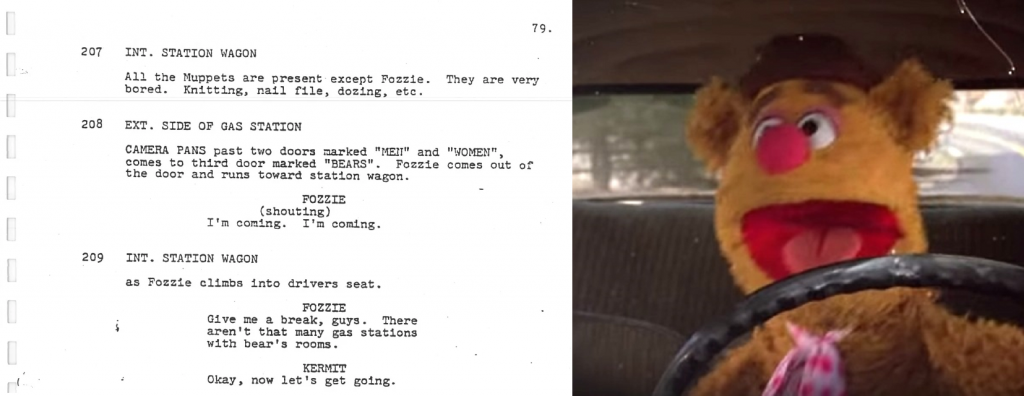

Here are some great examples of exposition written into the screen play:

- The audience learns about flying broomsticks and magical racing by overhearing a group of children exclaiming about “the new Nimbus 2000; it’s the fastest broom ever!” in Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone.

- The narrator’s voiceover in A Christmas Story explains why he hates his gift of fuzzy rabbit pajamas so much: “I knew that for at least two years, I would have to wear them every time Aunt Clara visited us. I just hoped that Flick would never spot them, as word of this humiliation could easily make life at Warren G Harding School a veritable hell.”

- Characters in The Office and Deadpool frequently “break the fourth wall” by directly addressing the audience to explain their motivations or provide further information.

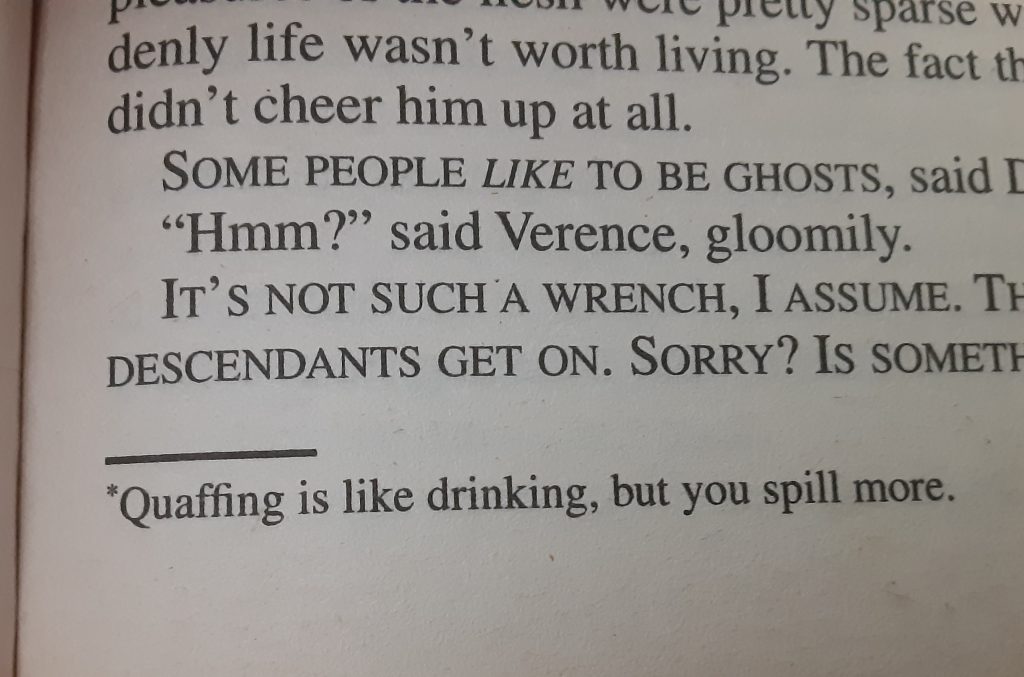

Sir Terry Pratchett included lots of footnotes in his novels, often providing extra jokes or humorous observations. In the screen adaptation of Wyrd Sisters, this footnote is shifted to a dialogue between two characters.

“It’s like drinking, but you spill more.”

Writers for the screen use a variety of techniques give the audience necessary information without background essays. Writers of short stories, novels, memoirs, etc. can make use of some of these techniques to “show, not tell” the story.

Simplification

When moving from page to screen (or stage). writers must keep in mind the attention span of the viewer. A reader who forgets the details of military supply trains in War and Peace can just flip back a few pages, but it’s a bit more difficult for a film or TV audience.

Simplified Plot

Remember the Mafia in Jaws? How about the romance between Idgie and Ruth in Fried Green Tomatoes? The controversy around Project 100,000 in the Vietnam War as experienced by Forrest Gump?

There are lots of reasons to cut subplots from a film adaptation. The running time might not allow for it. Corporate or government sponsors might require controversial themes to be removed. It might just be a case of special effects or budget constraints.

Simplified Characters

Many film adaptations don’t include all the characters in the source material. They might clutter the screen, they might be too difficult to film, they might simply be another name and face that the audience would have to remember.

Screen writers might shift a cut character’s dialogue to another character, or they might remove it altogether.

Often, screen writers will combine similar characters for the sake of clarity. Michael Green’s adaptation of Death on the Nile has many such changes. Apart from the murderers, the murdered, and Hercules Poirot, nearly every character from the original Agatha Christie novel is combined with another character or removed altogether.

One could argue that the same principles apply when writing any sort of fiction. Short stories certainly have a finite number of characters and sub-plots they can include before they are no longer “short.” At what point does including or omitting details in a non-fiction work change it to a work of fiction? The question of whether to include or cut, develop or combine characters and themes is ultimately down to the writer.

Beyond Words

Film editors, CGI artists, composers, costume designers, set designers, directors, actors, and hosts of others contribute to the final creation of a film that an audience sees. The screenplay is only one component of the finished product.

Editing

Consider the moment in The Wizard of Oz when Dorothy first arrives in Munchkinland. There is no dialogue. The editor created a transition shot showing the change from the sepia-toned farmhouse to the full-color world of Oz.

Costumes

Amy Westcott, costume designer for the 2010 film Black Swan, dressed the main character all in white and pink during choreography and classroom scenes. This illustrates the character’s naivety as well as drawing the audience’s immediate focus. Character development is reflected in the gradual darkening of the costume, demonstrating internal conflict without a single word being spoken.

Music

The score composer(s) are responsible for a huge part of an audience’s emotional involvement in a film. The ominous Jaws theme by John Williams (no relation), the Moonlight score that “splits the difference between classical and codeine” by Nicholas Britell, the iconic music establishing time periods in Forrest Gump all tell a huge part of the story beyond the visual.

Other unspoken storytelling devices Sean Williams suggests

- The camera panning along a series of family photographs with fewer and fewer people, showing a character’s increasing isolation

- Focus on a clock face, burned down candle stubs, or an overflowing ashtray to demonstrate the passage of time

- Camera angles above or below eye level to demonstrate the relative importance, ego, or intimidation of a character

- Distorting and muffling background sounds to reflect a character’s disorientation

- Changing color palettes to take advantage of humans’ hard-wired responses to red (danger), blue (calm), etc.

- Adjusting camera focus to draw audience attention to foreground, background, or in between

Ultimately, this must come from the directors, editors, actors, composers, lighting specialists, sound editors, etc., etc., etc…. The screenplay is really just the beginning.

Prose writers may not be able to include fantastic music or ambient colors, but there are other tools available. Point of view shifts, chapter divisions, physical descriptions, and sensory details (beyond sight and sound) can all be used to direct a reader’s attention.

Sean Williams gave me a lot more information about writing for the screen, but I’m afraid I’d need about four years to learn what he covered over the course of his degree. For more details, check out George Mason University or The Los Angeles Film School.