Robert J. Koester studied lost person behavior in a systematic, scientific, statistical way and the result is what many consider to be the best book on search and rescue ever written. So maybe you’re thinking Whoopdedoo. I’m into fiction. Maybe you’re yawning and about to browse elsewhere. Read on instead.

This book contains invaluable nuggets to make your writing not only accurate but also richer. Its usefulness for mystery writers might be more apparent than for more general literary fiction, but consider all the ways and reasons someone might go missing—either as the primary plot line, or as a subplot that complicates everything.

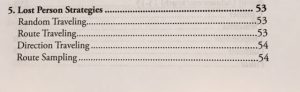

This book is useful whether you are writing from the POV of the missing person or the searcher(s). For example, it delineates strategies lost people use to try to get unlost, including the effectiveness of each.

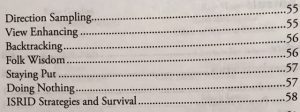

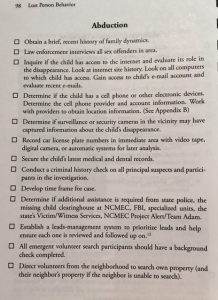

To aid the searcher, data are organized into 34 subject categories, ranging from Abduction through Urban Entrapment and Worker. Data about children are partitioned by age. Data on Skiers are partitioned by Alpine and Nordic. And so it goes. And for each Subject Category, there is an brief introduction, followed by guidelines for getting the search started and—perhaps of most interest to writers—pages of Additional Investigative Questions. For example, consider the usefulness of these questions concerning abductions.

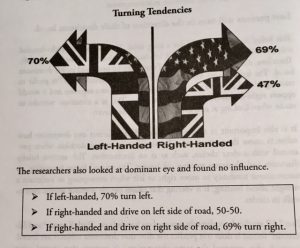

Perhaps my favorite chapter is 6. Lost Person Myths and Legends. For example, is it true that lost people will turn in the direction of their dominant hand? To some extent. When forced to make a clear choice between right and left, handedness matters. But the extent to which it matters is influenced by learned driving patterns.

People without visual cues do, indeed, walk in circles. Why? When blindfolded and told to walk in a straight line, whether one circles clockwise or counterclockwise is strongly influenced by which leg is longer. Too bad that bit of information is seldom available to searchers!

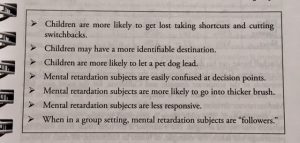

Potentially relevant information is everywhere in this book. Do the mentally retarded and children behave similarly when lost? Yes and no. The distances traveled from the initial planning point are quite similar for those with mental retardation and children 7-12 years of age. But there are important differences.

Dementia wanderers essentially travel straight ahead till they get stuck. Therefore, the most important first question to ask is, “Which door did he go out of?” Despondents, on the other hand, are most likely to just walk out and are most often found on a path, trail, or at their destination. Despondents are not truly lost.

I became aware of Koester’s book during a SinC/CentralVA program by 4 members of the Piedmont Search and Rescue staff. The book is expensive but you might well find it worth adding to your shelf.

The organization has an enormous amount of information and experience. You can find lots of it online.