I’m a jewelry junkie: even staying home I wear earrings, a necklace, a bracelet (only one, unless we’re talking bangles), and at least two decorative rings. If I didn’t wear a lot of jewelry every day, how could I justify having so much of it? For me, and for those who know me, it’s just my style: sterling silver with stones such as jasper, carnelian, onyx, and lapis lazuli.

Museum visits just aren’t complete until whatever jewelry displays are available have been viewed. There are quite a few you can visit online right now!

- Jewelry: The Body Transformed – Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Cooper Hewitt Museum – Smithsonian Design Museum

- Hooker Hall of Geology, Gems, and Minerals – Natural Museum of Natural History

- Wertz Gallery of Gems and Jewels – Carnegie Museum of Pittsburgh

- The Empress’s Jewelry Cabinet – Musée du Louvre

- Past is Present: Revival Jewelry – Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

- If that’s not enough shiny colors to satisfy your eyes, you can check out the list compiled by The Association for the Study of Jewelry and Related Arts of the best museums around the world with jewelry displays.

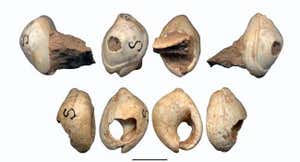

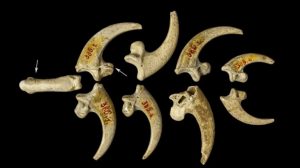

It might be argued that jewelry has been around as long as humans have. The oldest known human jewelry is 100,000-year-old Nassarius shells that were made into beads. An archaeological dig in Croatia provided some evidence that Neanderthals might have made jewelry from 35,000 years before that!

As you probably know, jewelry has been made from such natural materials as bone, animal teeth, shells, pearls, wood, carved stones, and many combinations thereof—and it still is! The term baroque comes possibly from the Portuguese baroca for a misshapen pearl. Less stable materials have rarely withstood the test of time, but people have and do make fabulous adornments from feathers, animal skins, paint, clay, dried leaves, flowers, paper, and even hair. And consider how many body parts you’ve seen adorned with jewelry—for example hairpins, tiaras, earrings, nose rings, neck rings, finger rings, toe rings…

Throughout history, people of high importance or status have historically had more jewelry than others, and often were buried with it. Burial spots of Viking chiefs, Egyptian nobles, and Chinese warlords are identified as such because of the fancy weapon and fabulous jewelry next to the corpse. In Ancient Rome, only people of certain ranks could wear rings.

But I started by saying jewelry can be more than beautification. In earlier times, jewelry served to pin clothes together, to restrain hair, to hide weapons, and as a method of storing wealth.

Identification

Can we count dog tags as jewelry? Made specifically for the purpose of identifying military, they have a long and erratic history. In English, the term “dog tag” comes from the resemblance to animal registrations.

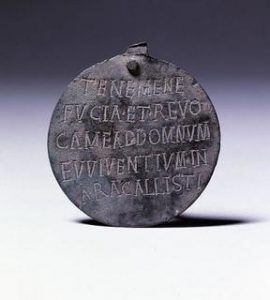

The earliest mention of an identification tag for soldiers comes in the writings of Polyaenus, who described how the Spartans wrote their names on sticks tied to their left wrists. A type of dog tag (“signaculum“) was given to Roman legionaries at the moment of enrollment: a lead disk on a leather string, worn around the neck, with the name of the recruit and the legion to which the recruit belonged.

Dog tags were provided to Chinese soldiers as early as the mid-19th century. During the Taiping revolt (1851–66), both the Chinese Imperial Army regular servicemen and rebels wearing a uniform wore a wooden dog tag at the belt, bearing the soldier’s name, age, birthplace, unit, and date of enlistment.

U.S. military personnel have worn dogtags since 1918, primarily for the purpose of handling casualties and deaths. (FYI: There were no official dog tags during the American Civil War. Some soldiers pinned pieces of paper with identifying information to their clothes. A few enterprising jewelry makers started making custom-ordered identification pins for soldiers to buy.)

Consider other types of ID jewelry: ID bracelets, pendants that spell out a name (usually only a first name). In some places, slaves were made to wear permanent bracelets or necklaces identifying their position and owner. In the days before photographic IDs, people used signet rings to prove their identity when giving orders or sending letters.

Information

Dog tags show more than just identification; they now include basic medical details like blood type and inoculations as well as religious affiliation.

The military is big on jewelry to convey information: number of stripes, number of stars, Purple Hearts, and other medals proclaiming one’s expert standing or honors.

Medical alert jewelry (typically bracelets) to proclaim diabetes, a heart condition, serious allergies, etc., in case medical treatment is needed for someone who cannot talk.

In past years, “mourning jewelry” made of jet or the woven hair of the deceased proclaimed one’s grief—often for a specified period of time, depending on relationship. Malaysian, Aztec, Chinese, Indian, Zulu, Egyptian, and Celtic funeral traditions all include specific jewelry for the corpse or the bereaved. The Victorians (of course) had incredibly detailed and strict rules about what type of mourning jewelry was to be worn, by whom, for which occasion, and for how long after a loved one died.

Traditionally, Japanese women’s hair and hair accessories were practically a résumé in code. The type and placements of a woman’s kanzashi (簪) hairpieces signified marital status, age, profession, social class, training level, etc. The most elaborate hairstyles and kanzashi were worn by geisha, courtesans, and women studying arts such as flower arrangements and tea ceremonies. Kanzashi were originally worn to ward off evil spirits, and they often doubled as weapons.

Maasai women communicate similar status messages in traditional bead-work. Traditionally, every woman learns how to weave together the intricate bead patterns and designs. The jewelry design and color indicates the family a person is from and how wealthy the family is. It also indicates the status of a Maasai woman, whether she is single, engaged or married.

And, of course, wedding rings signaling that (presumably) one is not available for romantic or sexual relationships. (FYI, wedding rings for men are relatively recent: by the mid-1940s, 85% of weddings included rings for both bride and groom.) Throughout most of Europe and America, wedding rings are worn on the left hand. In some countries, particular in Eastern Europe and Central Asia, wedding rings are worn on the right hand.

Affiliation

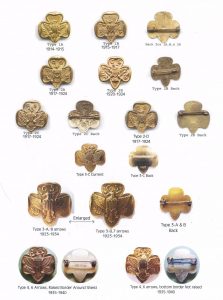

This may be the most common use of jewelry of all (except as pure adornment). On college campuses, Greek fraternities and sororities each have their unique “pins,” worn by members. Consider the jewelry Masons wear, and the rings worn by “Eastern Star” members, the group for women affiliated with a Mason. Other fraternal organization that have nothing to do with college campuses abound, along with their identifying jewelry.

Girl Scouts and Boy Scouts have pins declaring their rank and troop number, but other pins and badges are earned through service and awarded like military honors. Nurses, doctors, firefighters, paramedics, dentists, and many other professionals are presented with pins when they graduate. The pin is a sign of certification and of membership in the group.

The United States Congress has an entire system of jewelry for members. Lapel pins, ribbons, and necklaces show which party a Senator, Representative, spouse, or page belongs to and which Congress they are a member of. Each Congress designs a new design and color scheme.

Jewelry made of precious metals and precious gems, especially designer jewelry, clearly proclaim wealth, and sometimes status. Societies that are very conscious of class divisions are more likely to place importance on specific types of jewelry worn in public.

Ancient Egyptians used symbols on their jewelry to show territorial pride. The white vulture represented Nekhbet, patron of the Upper Egypt, and the red cobra stood for Wadjet and Lower Egypt. When the kingdoms were combined, the Pharaoh signified leadership of Upper and Lower Egypt by wearing a crown with a both the cobra and the vulture.

During the Medieval period in Europe, royalty and nobility considered the wearing of fashionable clothing and jewelry a special privilege reserved for themselves. To enforce this idea, sumptuary laws were initiated, primarily in the 14th century. Such laws were meant to curb opulence and promote thrift by regulating what people were allowed to wear. The English sumptuary laws forbade clothing and jewelry of certain materials, above certain price levels, of certain sizes, etc.

Religious affiliation can be signaled by jewelry, usually with symbols of the faith itself, though sometimes with the presence or absence of the jewelry or by what is covered by the jewels. The Star of David for Jews, a crucifix or a stylized fish for Christians. Buddhists may wear a lotus blossom or an image of Buddha. People who fervently believe in the power of Hogwarts may wear the Sign of the Hallows or a symbol of their House mascot.

Communication

All of the above involve communication of some sort. The Smithsonian has a traveling exhibit on jewelry as a form of language and expression, particularly the pins of Madeleine Albright. The former Secretary of State loaned her extensive collection of brooches, many of which had specific messages for those in the know. Queen Elizabeth Tudor is rumored to have had a similar system of jewelry signals for her vast network of spies, but nothing has ever been proven (probably because historians are not spies).

Secret messages can be communicated through jewelry even if the wearer is not a politician. In communities where homosexuality is illegal, LGBTQ people will often develop among themselves a discreet code of earrings or particularly colored necklaces. In America before the 1970s, this often took the form of a ring on the pinkie finger or a single earring in the left earlobe. During the American Civil War, abolitionists in Confederate States wore a red ribbon or string to signal that they would help escaping slaves move to safety.

Small squares of colorful beads known as Zulu Love Letters are gaining popularity in South Africa again. Like Maasai necklaces, each bead’s color and its placement in relation to others has a meaning. Together, the beaded designs send a message of love or affection.

Perhaps the most ephemeral jewelry of all—flowers—have a very long history of communicating when worn as adornments. Flowers and greens mean different things in different cultures, but they nearly always mean something pleasant when worn on the body. Hawaiian orchids woven in a lei with jasmine blossoms, carnations, or kika blooms are given as a sign of welcome or farewell. The Victorians had such a specific flower code that people could have entire conversations without saying a word, just by wearing combinations of blooms at various times.

Protection

In addition to wearing a religious symbol as a way of declaring one’s membership in a group, many people wear religious amulets or reliquaries for protection from evil influences. In the Middle Ages in Europe, ecclesiastical rings worn by clergy and laymen as sacred emblems, were one of the few exceptions to the nobility’s limits on jewelry.

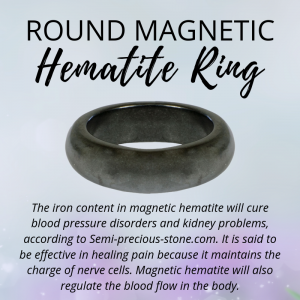

Curative rings, meant to cure ailments and diseases, were another exception to Medieval sumptuary laws. Necklaces with pouches of herbs, hair ornaments made of holy or lucky materials, and bracelets blessed by clergy are just a few of the ways people have used jewelry in an attempt to guard their health.

Many cultures allow women ownership only of her jewelry, given to her as bride gifts or a dowry. This can give women some degree of financial freedom. She will have ready access to cash if there is an emergency or if she needs to leave her home.

Jewelry can also double as weapons! Roman women wore hairpins that were long enough to be used in self-defense. Rings can double as a variation of brass knuckles or contain poison. Necklaces and very long bracelets can be turned into garrotes or used to tie up an enemy. An enterprising magic user can attach hex bags or cursed amulets to necklaces given as gifts. All sorts of useful methods of assassination can be hidden in lockets, brooches, arm cuffs, or anklets.

Domination

One of the first requirements of becoming an Evil Overlord is to acquire some piece of jewelry (usually a ring) that provide power or subdue the will of enemies. Otherwise, all the other Evil Overlords will laugh.

Three Rings for the Elven-kings under the sky,

Seven for the Dwarf-lords in their halls of stone,

Nine for Mortal Men, doomed to die,

One for the Dark Lord on his dark throne

In the Land of Mordor where the Shadows lie.

One Ring to rule them all, One Ring to find them,

One Ring to bring them all and in the darkness bind them.

In the Land of Mordor where the Shadows lie.

Bottom Line for Writers: As with everything about your characters, consider their jewelry choices and the whys therefore!