Denise Chan – Chinese Opera, CC BY 2.0

The men’s beauty and makeup market, already a billion-dollar industry, is expected to grow to nearly $20 billion by 2027.

A recent survey on Ipsos found that among heterosexual men ages 18-65, 15% reported currently using male cosmetics and makeup, and another 17% say they would consider doing so in the future.

Who were the nay-sayers? 73% of men 51 and over, compared to 37% of men 18-34.

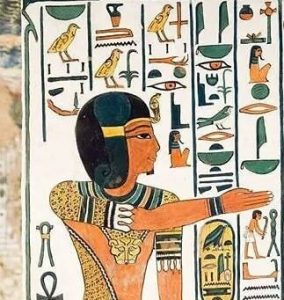

Makeup on Ancient Male Faces

Some might wonder “What’s the world coming to?” A more accurate question might be, “What’s the world getting back to?” An article—with pictures—at humanistbeauty.com makes the following five points about men’s early use of cosmetics.

from New Hanfu

Men were wearing makeup as long ago as 3000 BCE in China and Japan. Men used natural ingredients to make nail polish, face powder, rouge, and eyeliners, all signs of status and wealth. Archaeologists found a “portable” makeup box with a bronze mirror, large and small wooden combs, a scraper, and powder box. In the Han Dynasty, civil servants known as Lang Shi Zhong wore elaborate makeup and hairstyles when they appeared in court. Male attendents of Emporer Hui (210-188 BCE) of the Han Dynasty were forbidden “to go on duty without putting on powder.”

In ancient Egypt, men rimmed their eyes in black “cat” eye patterns as a sign of wealth (it also helps to reduce sun glare — as modern baseball and football players have found). They also wore pigments on their cheeks and lip stains made from red ochre. Makeup was an important way of showcasing masculinity and social rank.

In ancient Korea, the Silla people believed that beautiful souls inhabited beautiful bodies, so they embraced makeup and jewelry for both genders. Hwarang, an elite warrior group of male youth, wore makeup, jade rings, bracelets, necklaces, and other accessories. They used face powder and rouge on their cheeks and lips.

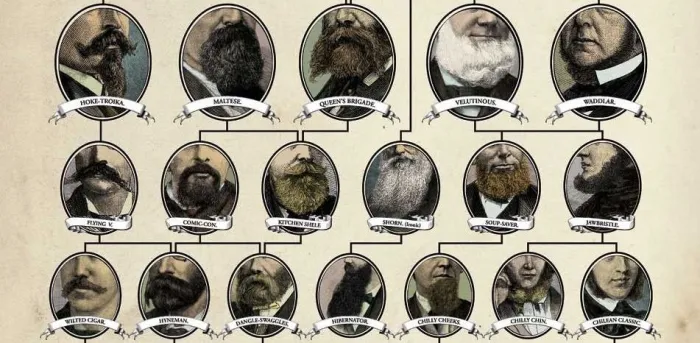

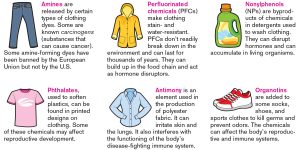

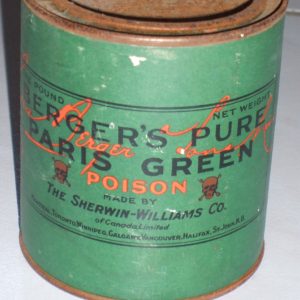

Skipping to Elizabethan England: the goal was for skin to look flawless. Men powdered their faces to whiten the skin as a sign of wealth, intelligence, and power. Fashionable courtiers dyed, curled, starched, and waxed their beards and moustaches into elaborate arrangements. To achieve the desired effect, men spent hours painting their faces, necks, hands, and hair into fantastic conifgurations that lasted for days before being removed. However, cosmetics during the Elizabethan age were dangerous due to lead, mercury, arsenic, and allum in the majority of products. These cosmetics could lead to blindness, seizures, hair loss, sterility, and premature death.

Makeup on More Recent Male Faces

from The genius of William Hogarth

Men’s love affair with makeup—for specific purposes, traditions, and enjoyment died a slow death in the 18th century when Queen Victoria associated makeup with the devil and declared it a horrible invention.

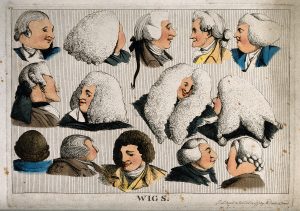

I read somewhere or other that George Washington issued a pound of flour with each soldier’s rations for use on his wig or hair. Though few soldiers wore full wigs, many attached fake plaits to their own hair or the backs of their hats. During the Revolutionary War, American wig and hair fashions were much less elaborate than those of British aristocrats, like the simpler fashions for ladies’ dresses on this side of the Atlantic. (Washington himself curled and powdered his own hair rather than wearing a wig; he was a natural redhead!)

After the American Revolutionary War, the use of visible “paint” (color for lips, skin, eyes, and nails) gradually became socially unacceptable for both sexes in the U.S. Painting one’s face was considered vulgar and was associated with prostitution and actresses/actors. But did people stop using them?

Of course not! True, few cosmetics were manufactured in America during most of the nineteenth century. However, folks (mostly women) went DIY, using recipes that circulated among friends, family, and sometimes printed in women’s magazines and cookbooks.

Although original sources are hard to come by, you can find some on Kate Tattersall’s blog entry on Victorian Make-up Recipes; powders, lip salves, creams, & other cosmetics of the 1800’s. Here are a couple of examples.

Lip Salve

Take 1 ounce of white wax and ox marrow, 3 ounces of white pomatum, and melt all in a bath heat; add a drachm of alkanet, and stir it till it acquire a reddish colour.

To Blacken the Eye-lashes and Eye-brows

The simplest preparation for this purpose are the juice of elder-berries; burnt cork, or cloves burnt at the candle. Some employ the black of frankincense, resin, and mastic; this black, it is said, will not come off with perspiration.

Pearl Powders, for the Complexion

1. Take pearl or bismuth white, and French chalk, equal parts. R educe them to a fine powder, and sift through lawn.

2. Take 1 pound white bismuth, 1 ounce starch powder, and 1 ounce orrispowder; mix and sift them through lawn. Add a drop of attar of roses or neroli.

Of course, the simplest way to “lighten” the complexion was with starch, applied with a hare’s foot or soft brush. Pale skin indicated social class/wealth: brown skin signaled outdoor labor.

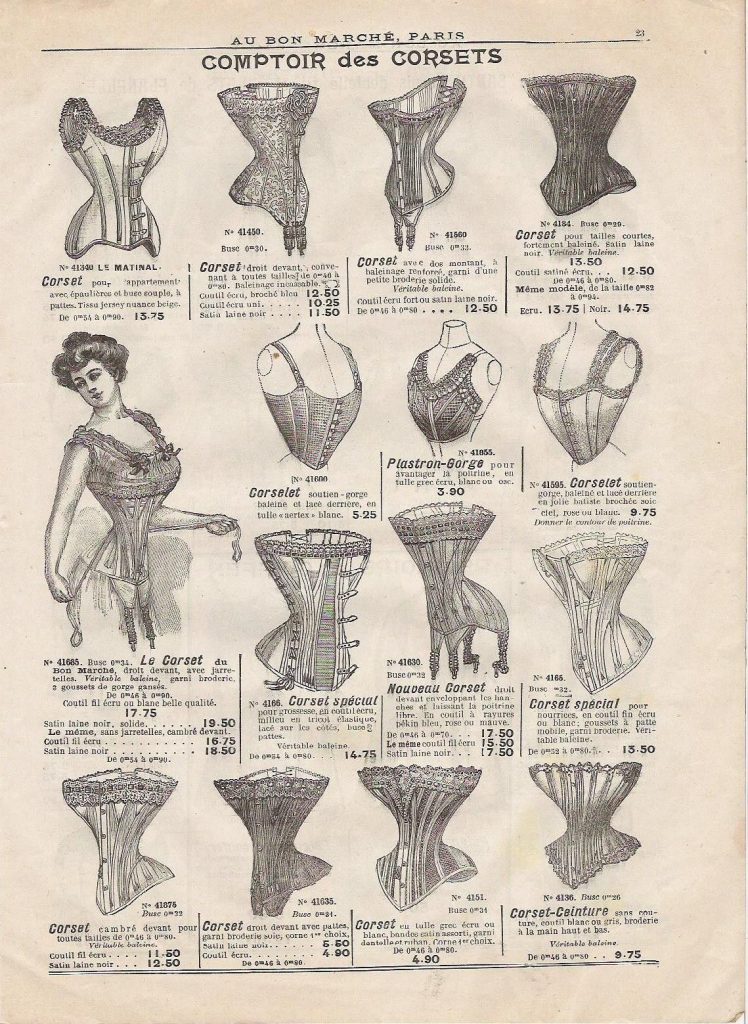

Thus lotions, powders, and skin washes—to lighten complexions and diminish the visibility of blemishes or freckles—remained in use.

Druggists sold ingredients for these recipes, and sometimes ready-made products. Given the association of “paint” with prostitution (and actors), products needed to appear “natural.” Some secretly stained their lips and cheeks with pigments from petals or berries, or used ashes to darken eyebrows and eyelashes.

Technological advances in photography, interior lighting, and creating reflective surfaces led to a rise in “visual self-awareness” throughout the 19th and 20th centuries. This, coupled with a rise in wide-spread advertising through print mediums, created a wider market for commercially produced cosmetics.

In the late 1960s, norms again celebrated ideals of natural beauty—as in the Victorian era—including a rejection of make-up altogether by some. Cosmetics companies returned to touting products for a “natural” look.

Makeup on Performing Male Faces

by Saad Akhtar

Makeup for actors never went out of fashion, so it’s no surprise that the recent increase in makeup use for men has been led by entertainers. Performers used cosmetics as part of costumes or to ensure their facial features remained visible on stage or on screen. Stylized makeup designs correspond to specific roles in classical forms of Japanese, Thai, Indian, and Chinese theater traditions.

The popularity of the Ballet Russe in Paris in the beginning of the 20th century led to an increase in the social acceptability of wearing makeup. When the Ballet went on tour, there was a corresponding boom in cosmetic sales and advertising in countries where they performed.

Waves of glam rock, heavy metal, goth, and punk musicians in the 1970s and 1980s inspired legions of fans to don makeup to perform and to disrupt social norms. Just think of KISS, Mötley Crüe, Marilyn Manson, King Diamond, Boy George, or Alice Cooper.

The elaborate makeup and costumes of Glam Rock stars such as Boy George and David Bowie challenged gender expectations.

Heavy Metal performers such as Alice Cooper and Marilyn Manson are as recognizable for their stage makeup as for their stage costumes and music styles.

.

Makeup on Modern Male Faces

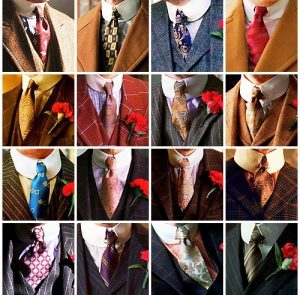

Men are now open to using a variety of products, including facial cleansers, exfoliants, serums, moisturizers, and most recently, cosmetics.1

For centuries, gender binaries established during the 17th and 18th centuries influenced who typically wore makeup–women! But make-up for men (and those who identify as male) may be here to stay—and goes way beyond entertainers and political statements.

Young Yuh, who has 1.6 million followers on TikTok and posts skin care and makeup tutorials full-time, says makeup is key to his self-expression. His view is that it’s like hygiene, or hairstyle, or any number of other personal choices and should not be bound by gender identification. His daily routine includes cleanser, toner, some type of serum, moisturizer, sunscreen, primer, concealer, contour, blush and eyeliner—no doubt a bit much for many!

The hashtag #meninmakeup has more than 250 million views on TikTok. And The New York Times Style Magazine article “Makeup Is For Everyone” gives a great overview of the most recent developments and resources online.

In 2017, Maybelline launched their Collosus mascara campaign featuring Manny Gutierrez with the tagline “Lash Like a Boss.” Patrick Starr, a Filipino-American makeup artist and fashion designer, collaborated with MAC makeup to launch a collection of his own design. In 2016, Gabriel Zamora became the first male makeup artist to join Ipsy makeup. Advertisements both reflect the current culture and feed it.

Bottom line: Men are now open to using a variety of products, including facial cleansers, exfoliants, serums, moisturizers, and most recently, cosmetics.

(Writers note: depending on your audience, you might want your guys’ grooming to include more than a shave and a hair cut.)

by Etan Doronne