By Muhammad Adzha

English is pretty anaemic when it comes to scent. We have to attach adjectives like “putrid” or “mown grass.” On the other hand, the Jahai people of Malaysia have words attached to specific smells, with meanings like “to have a stinging smell, to smell of human urine,” and “to have a bloody smell that attracts tigers.’

Researchers at Rockefeller University estimated that humans can detect at least a trillion distinct smells. That leads me to conclude that need determines what we do with specific ones. This conclusion is supported by other evidence: in tribes that have recently switched from hunting and gathering to farming, smell words often vanish.

Abigail Tucker explores the sense of smell in the Smithsonian Magazine article “Scents and Sensibility.” (Full reference below). Do read it! To whet your appetite, here are some bits that I found particularly interesting.

Scents and the Body

Females are more sensitive to smells than males.

Research indicates that infants are habituated via mothers’ milk to react more positively to the smell of things the mothers eat.

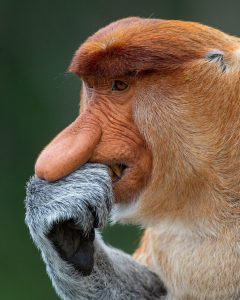

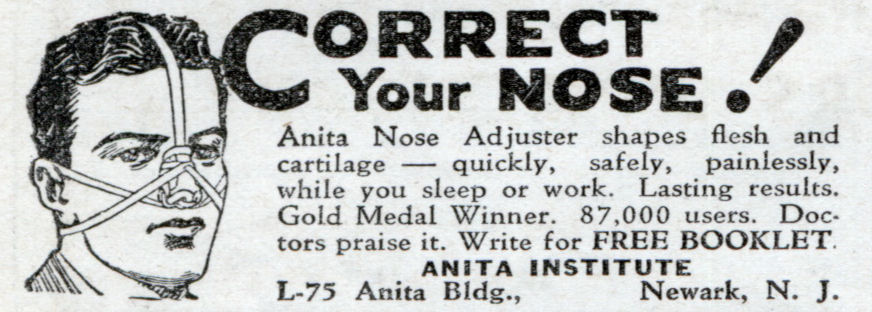

The human nose comes in 14 basic shapes and sizes.

(FYI, not in the article: noses and ears do not continue to grow during adulthood. They do change shape, however, due to skin changes and gravity.)

Many “tastes” are actually smell; chocolate, for example.

(I remember a classic psychology experiment that demonstrated that, without olfactory or visual clues, people couldn’t tell bits of apple from bits of onion.)

The exposed nature of scent receptors in the nose make them especially vulnerable to environmental toxins.

Apparently olfactory receptors can become fatigued.

The sense of smell declines with age, especially in those over 50. By age 80, 75% of people exhibit what could be classified as a smell disorder. (Oh, sigh.)

Pretty much everyone has “blind spots” when it comes to smell. For example, not everyone can smell asparagus in their pee—but if you can, you can smell it in anyone’s urine.

Also not covered in this article: virtually everyone can become noseblind when exposed to the same smell for a prolonged period of time. Consider entering a room and noticing an odor at first but not later.

Scent Power

A human without visual or auditory cues can track a scent through the grass of a public park—but not as well as a dog can.

Some psychological conditions affect sense of smell. For example, research has linked autism to an enhanced sense of smell. On the other had, depression and Parkinson’s disease are related to decreased sensitivity.

Culture affects what we smell and how we react to specific smells.

Besides genetic and cultural factors, certain smells evoke a visceral reaction specific to the individual, depending on life history. Research participants are able to access more emotional memories when exposed to a smell as opposed to a picture of the source of the smell.

Andreas Keller, a prominent neuroscientist specializing in olfaction, has opened a gallery, Olfactory Art, where smell is central to the experience!

How does the nose know? We still don’t know! “Olfaction has always been an underdog sense. It’s both primitive and complex, which makes it hard to study and harder still to transfer to our increasingly digital existence. … smells cannot at this point be recorded or emailed or Instagrammed.”

In a 2011 survey, more than half of the young adults said they’d rather give up their sense of smell than their cell phones. Little did they know what that sacrifice would entail.

BOTTOM LINE: COVID’s notorious effects on the sense of smell has triggered a new appreciation of the role of scents in our lives, for both pleasure and safety.

“Scents and Sensibility” by Abigail Tucker, Smithsonian Magazine, October 2022, pp 66-80.